“Long hunters brought the rifle sufficient attention that the Continental Congress began calling for independent rifle companies in 1775.”

By John Danielski

ZZZZZPT! The angry hornet-like sound of a rifle round in flight caused anxious redcoats to cast their eyes toward their general. They could not see the shooter; the gun smoke of battle and the dense woods of upstate New York masked his position. They nonetheless guessed he was one of Daniel Morgan’s riflemen. British general Simon Fraser clutched his breast and slowly tumbled from his horse: dead before he hit the ground.

An American frontiersman named Timothy Murphy fired the shot that killed Fraser on Oct. 7, 1777. A well-liked and capable leader, Fraser was in the act of rallying his troops when he was struck down. Had he succeeded, he might well have delayed the decisive American victory at Saratoga.

Murphy’s weapon was a uniquely American creation of a kind used by most of the 500 men of General Daniel Morgan’s Corps of Riflemen. Its nickname was “the widow-maker,” a grim title bestowed by the British because of its depredations against officers. It went by various other names: long rifle, American Rifle, Dickert Rifle, and Pennsylvania Rifle. However, it is best remembered by a designation bestowed considerably later: the Kentucky Rifle.

Riflemen were best employed as snipers against high value targets, like redcoat officers. When sheltered behind an army wielding muskets and bayonets, the long rifle’s slowness to load and lack of a blade attachment were acceptable drawbacks. Fraser’s regulars eventually drove off Morgan’s riflemen with cold steel in the opening round of Saratoga at Freeman’s Farm on Sept. 19. But when the battle resumed at Bemis Heights on Oct. 7, Morgan’s immediate superior, Benedict Arnold, assigned his subordinate’s best marksman to remove Fraser from the fight.

From his perch ten feet up in a pine tree, Murphy fired first to find the range, which turned out to be 300 yards: a formidable distance even for a skilled rifleman.

An aimed shot severed the bridle of Fraser’s horse. The next passed to the rear of Fraser’s head and killed an aide. Several officers begged the general to dismount but he told them an officer needed to be conspicuous to inspire his men. The third round struck Fraser in the chest.

Murphy’s rifle reflected an ancestry that was both German and English. Early 18th century settlers from Moravia and Switzerland arrived in Pennsylvania bearing stubby jaeger rifles.

Unlike the smoothbore weapons used by most hunters, the lands and grooves of the jaeger’s rifling spun the ball as it left the barrel, which gave it far greater accuracy in flight. A jaeger was generally 40 to 45 inches in length, weighed between nine and 11 pounds, and fired a round between .50 and .70 caliber. It was painfully slow to load compared to a musket: a round needed to be pounded into the barrel with a mallet before finally being rammed home. That operation not only consumed time, but deformed the ball, thereby reducing accuracy.

The large size of the round also necessitated a heavy powder charge. Powder was easily available in central Europe, but in the New World it costly and in shorter supply. And because of the short length of the barrel, a charge’s explosive potential could not fully develop.

The German speaking jaeger users in southeast Pennsylvania were soon introduced to the English fowling piece: a smoothbore used for hunting small game. Specimens were generally between 55 and 70 inches in length, weighed seven to eight pounds, and fired a round between .31 and .45 caliber.

Sometime around 1730, immigrant gunsmiths living in Bucks and Nazareth counties of Pennsylvania mated the two weapons and developed a hybrid that suited the unique needs of frontiersmen for whom hunting was not a sport but a necessity.

Instead of having a ball hug the rifle’s grooves directly, the new weapon employed a leather patch greased with lamb tallow. The patch eliminated the need for a mallet and drastically shortened loading time. The patch also reduced the escape of gases, increasing hitting power. The patch exited the barrel with the round, but immediately fell away.

Arriving in Pennsylvania from Mainz in 1747, Jacob Dickert was far from the first gunsmith to make a long rifle, but such was his skill and impact upon apprentices and other gun makers that by the late 1760s, many started to call any long rifle made in Pennsylvania a “Dickert.” By the start of the Revolutionary War, other immigrant gunsmiths who had settled in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina were copying his style.

A typical Dickert rifle was 54 to 65 inches in length, with a 42 to 44-inch barrel. They weighed between seven and eight-and-a-half pounds with a caliber of .44 to .55. The barrels were generally octagonal and swamped – meaning they were wide at the breech and muzzle and narrow in the middle – allowing for a thinner stock and better balance. The barrels usually had seven or eight lands and grooves that gave the ball one of three twists; one in 48 inches, one in 60, and one in 66.

Balls achieved a velocity of 1,200 to 1,500 feet per second: far slower than a modern M-16 bullet. Rounds grew smaller as the 18th century wore on resulting in the conservation of lead and reducing the mangling of game. If a rifleman faced a larger quarry, he simply increased the quantity of powder.

Most rifles had a simple blade front sight and a rear one that was an open “V.” A raised wooden cheek piece on the reverse of the butt stock facilitated aiming.

In the hands of a competent marksman, a Pennsylvania rifle had an effective range of 200 yards against an individual. Musket balls fired at man-sized targets from 100 yards generally hit them less than 50 per cent of the time. The Shain Brothers of Captain Michael Cresap’s Company of Rifleman gave a demonstration of what was expected of skilled riflemen in 1775. Firing from 60 yards away at a five by seven-inch square piece of board atop a five-foot pole, each brother was able to put eight out of eight rounds into the center of the target, which had the likeness of a man’s face drawn on in charcoal.

Pennsylvania gunsmiths used local hardwoods for stocks. Curly maple, also known as tiger stripe maple, was preferred. Other woods included cherry, black walnut and dogwood. The first rifles had thick butt stocks in the manner of the British Brown Bess musket and the French Charleville; later models had thinner, more streamlined butt stocks and featured curved, rather than straight butt plates. Many showcased baroque and rococo carving on the rear of the butt stock; making them early examples of American decorative art.

The furniture was usually of brass, though iron was used on early pieces dating from the 1740s. Typically that brass included a nosecap, ramrod pipes, and butt and side plates. Many sported a rectangular metal patch box on the front of the butt stock; earlier weapons had wooden ones with sliding tops. Ramrods remained wooden.

Pennsylvania rifles first saw combat at Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 and small numbers of them were used in the French and Indian War.

In 1826, James Fenimore Cooper created the classic character Hawkeye in his best-seller The Last of the Mohicans, a fictional archetype who embodied the hardiness, pluck and independence of the men who carried rifles in that conflict. In fact, Cooper’s iconic protagonist was often referred to by his French opponents la Longue carabine: “long rifle.”

After the war’s end in 1763, frontiersmen like John Sevier carried rifles into the wilderness beyond the Appalachians.

Threatened by British Major Patrick Ferguson during the Revolutionary War, Sevier marched his “Over Mountain Men” back into South Carolina and decisively defeated Ferguson at the Battle of King’s Mountain on Oct. 7, 1780.

Ferguson, occupying the top of the mountain, used a downhill bayonet charges to drive off the encircling riflemen, but Sevier’s troops simply melted into the heavily wooded terrain and sheltered behind boulders and fallen trees. The Rebels were used to firing uphill and poured an accurate fire into Ferguson’s men who were silhouetted against the sun. It was the only battle of the war in which most of the Americans were armed with rifles rather than muskets.

Daniel Boone did more than any other single man to forge an association between long rifles and Kentucky. He carried a rifle that he christened “The Tick Licker,” because it was supposedly so accurate, he could shoot a tick off the rump of an animal without damaging the beast’s hide.

During his lifetime, Boone possessed at least three weapons that bore that appellation. Although one specimen in a Kentucky museum marked “DB” has long been associated with Boone. Although that link is tenuous since the rifle was made between 1820 and 1830 and Boone died in 1820. Likely the weapon Boone carried when he established Boonesborough in 1775 was similar to a Dickert rifle.

Boone’s best shot came at the siege of Boonesborough in September 1778. An aide to the Shawnee Chief Blackfish who was besieging the fort exposed the top of his head for a second at 250 yards. Firing from behind the fort’s palisades, Boone’s round neatly removed half of his skull.

Long hunters brought the rifle sufficient attention that the Continental Congress began calling for independent rifle companies in 1775. Numerous volunteer companies were formed from backwoodsmen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Daniel Morgan, born in New Jersey but long a resident of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, became the most famous exponent of this unique arm. The Congress placed numerous orders for rifles with gunsmiths in the central colonies: including a curious request for a rifle “fitted with a telescope.”

Although Washington himself owned two rifled pistols that were small versions of Pennsylvania rifles, he expected to fight a European-style war using conventional linear tactics. Smoothbore muskets would dominate the field – blunt instruments for soldiers with blunt training. Precision tools, like rifles, would be relegated to a few skilled specialists who often chafed under conventional discipline.

Speed counted for more than accuracy in European warfare; the sheer amount of lead that could be placed in the air in a short time decided a battle. Because of rifling’s lands and grooves and their varied calibers, large quantities of paper cartridges prepared in advance were impractical. Each rifle had to be carefully loaded from a powder horn and a leather patch cut for each round.

Riflemen usually carried a tomahawk in lieu of a bayonet, but they fared poorly against a 17-inch blade attached to the muzzle of a musket. In a world of single-shot weapons, the impact of a bayonet charge was often decisive.

Maintenance for rifles was also a problem. Unburned powder fouled rifle barrels much faster than muskets. And while conventional musket components were not yet quite interchangeable, finding a replacement part was not difficult. On the other hand, each rifle was unique; substitute parts had to be specially crafted.

The so called “Golden Age” of the Pennsylvania rifle began in 1785 and lasted until 1825. The rifle developed many distinctive styles as gunsmiths began to build variants in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio. Butts and stocks continued to narrow and thin and a strongly curved butt called a Roman nose, first seen in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, became a popular refinement. Double-set triggers and finger rests on trigger guards were often added.

Rifles became fully fledged works of art as well as weapons. Some gunsmiths signed their works on side plates, escutcheon ovals and barrels in the manner of old master painters. Brass patch boxes featured floral designs and inlays of German silver graced stocks. Popular patterns included geometric shapes like ovals, circles, and rectangles. Objects such as compasses, stars, suns, moons, presidents, and Indians, as well as and animals like horses, deer, buffaloes, bears, and bald eagles also made appearances.

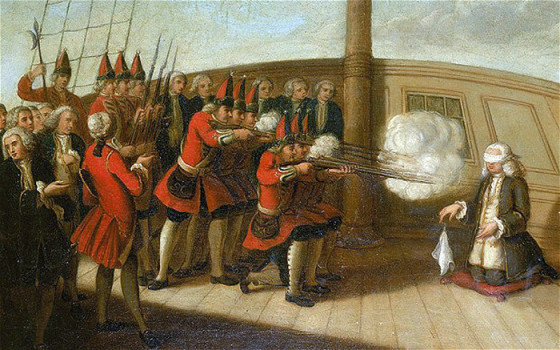

Pennsylvania rifles played much the same role in the War of 1812 as they had in the Revolution. They were chiefly used by Kentucky volunteers in battles in Ohio, Michigan, and Upper Canada; mounted riflemen played a prominent role in William Henry Harrison’s defeat of Henry Proctor at the Battle of the Thames on Oct. 5, 1813. A new use was their employment by U.S. Marine snipers posted in the fighting tops of ships like the USS Constitution.

Pennsylvania rifles achieved their greatest fame at the Battle of New Orleans, fought on January 8, 1815; three weeks after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed. One third of General Andrew Jackson’s 4,700 men were Kentuckians; many carried long rifles. The designation “Kentucky Rifle” first appeared in an 1822 poem celebrating their achievements.

The British suffered 2,000 casualties from their frontal attack on Jackson’s entrenchments along the Rodriguez Canal; many were victims of American riflemen. A British officer gave an iconic description of one Jackson’s marksman:

“I could see nothing but the tall figure standing on the breastworks; he seemed to grow, phantom-like, higher and higher, assuming through the smoke the supernatural appearance of some great spirit of death. Again did he reload and discharge and reload and discharge his rifle with the same unfailing aim, and the same unfailing result; and it was with indescribable pleasure that I beheld, as we marched [towards] the American lines, the sulphorous clouds gathering around us, and shutting that spectral hunter from our gaze.”

The tall figure spoken of by that British officer was believed to be Lieutenant Ephriam McLean Brank. A statue of him and his rifle graces the grounds of the Muhlenberg County Courthouse in Greenville, Kentucky.

“The Coonskin Congressman” Davy Crockett died wielding a Pennsylvania rifle at the Alamo in 1836. Two surviving weapons can be reliably associated with him though neither was used at the famous battle. The first was presented to him at age 17 in 1803 and made in York County, Pennsylvania around 1790. It was 60 inches long with a 44-inch barrel, featured a .50 caliber bore and weighed 9 pounds. The second was a presentation piece known as “Pretty Betsy.” The weapon was given to him by well-wishers when he left Congress in 1835. It was a .40 caliber weapon with a 46-inch barrel and cost $250, a considerable sum in the early 19th Century. The stock was trimmed in sterling silver with figures of the Goddess of Liberty, a raccoon, a deer’s head, an elk’s head, and an alligator over the trigger guard. Inscribed on the butt stock were the words, “Constitution and Laws.”

Percussion cap Kentucky rifles were made well into the 1850s, but the appearance of rifled muskets like the 1853 British Enfield that used Minié ball inspired projectiles signaled the end of their usefulness as military weapons. Still, many volunteers showed up with them at the start of the Civil War in 1861. Appalachian rustics continued to use them for “varmit” hunting into the early 20th century.

The great popularity of Disney’s Davy Crockett TV series in the 1950’s with its catchy, chart-topping themesong, “The Ballad of Davy Crockett,” renewed interest in American long rifles and turned them from simple weapons into folk icons. Even the character Jed Clampett used one in the title sequence of The Beverly Hillbillies starting in 1961.

While Pennsylvania rifles were only supplementary military weapons and the incredible feats of marksmanship ascribed to their owners frequently had more to do with tall tales than reality, they were a uniquely American creation: weapons as well as works of art. They helped to shape the classic image of the American frontiersman. In fact, it’s difficult to picture near-mythic figures like Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett without one. Though the rifle went by many titles, it was best identified by its deadly nickname: “the widow maker.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: John Danielski is the author of the Tom Pennywhistle series of novels about a Royal Marine officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Book five of the series, Bellerophon’s Champion: Pennywhistle at Trafalgar was published by Penmore Press in May 2019. Watch for Bombproofed, the next Pennywhistle adventure, coming in May of 2020. For more, visit: www.tompennywhistle.com or check him out on Amazon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: John Danielski is the author of the Tom Pennywhistle series of novels about a Royal Marine officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Book five of the series, Bellerophon’s Champion: Pennywhistle at Trafalgar was published by Penmore Press in May 2019. Watch for Bombproofed, the next Pennywhistle adventure, coming in May of 2020. For more, visit: www.tompennywhistle.com or check him out on Amazon.

Are there any reliable sources that describe specifically the rifle or rifles Daniel Morgan owned?