“As the Civil War began in 1861, memories of the previous war served as the pivotal frame of reference for the rising new generals.”

By Timothy D. Johnson

ON APRIL 9, 1865 Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met at Appomattox to formalize the end of the bloodiest war in American history. Lee reached the appointed meeting place first and a half hour later Grant arrived. They greeted each other with a silent handshake before taking their respective seats a few feet apart. After a few seconds of awkward silence Grant spoke first, reminding Lee that they had met 18 years earlier in Mexico. It was during General Winfield Scott’s 1847 Mexico City Campaign.

Grant was a lieutenant in the 4th Infantry and Lee was a captain on Scott’s staff during the Mexican-American War, and while the former was a relatively unknown quartermaster officer, the latter was a rising star in the army.

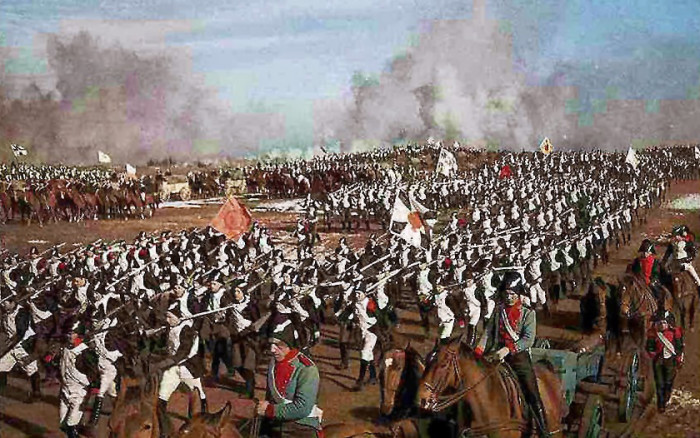

It seems odd that after four years of carnage in places like Virginia, Tennessee and Mississippi, the first topic that arose between the two men at Appomattox was the war with Mexico. However, upon closer examination, perhaps it was not so unusual that Grant opened their meeting with a reference to the earlier conflict. The general knew that Mexico was common ground for both of them as the two sat down to discuss the Confederate surrender. Many of the leading commanders on both sides of the Civil War had served a decade-and-a-half earlier in Mexico in what would be an important shared experience or, as one historian put it, a rehearsal for conflict. Indeed, over 300 future Civil War generals fought in Mexico and most of them (239) had served together in either Scott’s or Zachary Taylor’s armies in 1846 and 1847.

The Mexican-American War had been a defining moment in the development of their military careers. Major battles like Monterrey, Cerro Gordo, and Chapultepec fought in a distant land taught budding young officers many lessons while creating lasting memories. When Americans returned home, they assumed that they had just been through the greatest combat experience of their lives.

Grant called the attack on Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847, a “brilliant assault,” while Lieutenant Thomas J. Jackson thought Scott’s entire campaign was greater than “any military operations known in the history of our country.” Lieutenant William M. Gardner, a future Confederate general, asserted that the army’s accomplishments in Mexico would “astound the world.”

In 1848, the young army officers believed that they had just been through the great epic event of their lives; none could imagine that it was just a prelude to something much bigger and far bloodier that would overshadow the two-year conflict below the Rio Grande.

The magnitude of the Civil War eclipsed the previous war with its long shadow, making the Mexican conflict a forgotten war with the general population. Biographers of Civil War generals usually treat their subject’s experiences in Mexico as a minor event worthy of only a few pages. However, personal experience is a powerful teacher, and lessons learned in Mexico would have certainly informed future decision making when the lieutenants and captains became Union and Confederate generals. Mexico was a laboratory of experiential learning that reinforced lessons learned at West Point and fostered practical skills in battlefield tactics and in managing an army in the field. A deeper exploration of this topic, like the one offered in my 2024 book The Mexican-American War Experiences of Twelve Civil War Generals is overdue.

As the Civil War began in 1861, memories of the previous war served as the pivotal frame of reference for the rising new generals.

For example, following Fort Sumter, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard cited among his qualifications to lead an army his position on Scott’s staff in Mexico and his participation in councils and reconnaissances leading to the capture of Mexico City.

Major General George B. McClellan, in his action against Confederate forces at Rich Mountain in July of 1861 acknowledged that he attempted to “repeat the manoeuvre of Cerro Gordo.”

A month earlier when Confederates won a minor engagement at Big Bethel, Major General John B. Magruder exaggerated the battle’s significance by likening it to Scott’s victory in Mexico.

Later in the Civil War, while chastising the depredations against southern civilians perpetrated by Union troops, General Jubal Early referenced how he maintained order while serving as military governor of the city of Monterrey in 1847. Clearly, Mexico weighed heavy on the minds of the generals on both sides.

As the Civil War grew in scope and complexity, memories of Mexico were replaced with the immediacy of the enormous struggle unfolding. However, the influence of the previous war remained, and it should be viewed as an apprenticeship for Civil War commanders.

A few examples, beginning with Winfield Scott, will suffice to make this point. Scott’s plan to subjugate the Confederacy is known as the Anaconda Plan, and its formulation stressed the same kind of moderation that he had used during the Mexico City Campaign. His 1861 plan called for a naval blockade of the southern coastline to isolate the wayward states. Next, he advocated seizing the Mississippi River to divide the Confederacy and deprive it of that valuable waterway. Securing control of the river would cut off the Trans-Mississippi theater, ensuring that it would be no more than a sideshow just as he had done to northern Mexico in 1847. To execute his plan Scott explained that a strong Federal army would advance down the river capturing Confederate strongpoints similar to the way he had advanced through central Mexico outmaneuvering and defeating enemy forces. He also called for striking deep into the Confederate heartland just as he had done with his thrust inland to Mexico City.

Both in 1847 and 1861, Scott’s primary objective was the political subjugation of the opponent not the destruction of enemy armies. At no time during the Mexican War did Scott pursue a war of annihilation against the Mexican army. In fact, he expressly stated that his purpose in invading central Mexico was apply sufficient pressure to induce the enemy government to capitulate. He was prepared to stop his advance short of Mexico City if surrender terms had been requested. Similarly, the Anaconda Plan was less military than it was economic and political. A coastal blockade and control of riverways was an attempt at economic strangulation, not military obliteration. It was a different time with different circumstances, but in 1861 Scott instinctively saw relevance in past experience.

When George McClellan gained command of the Army of the Potomac he began planning what came to be known as the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. This ambitious undertaking should be seen as nothing more than McClellan’s attempt to replicate the Mexico City Campaign in which he participated. In 1847 Scott had executed a strategic turning movement by shifting the theater of war from northern Mexico to the east coast by utilizing secure water transportation to maintain his line of communication. This is precisely what McClellan did when he transported his army to the peninsula east of the Confederate capital. He intended to maneuver and fight his way to Richmond forcing the South to surrender, and he envisioned his operation as the primary blow that would win the war. Just as Scott had aimed his invading army at the political nerve center of the enemy, so too did McClellan. However, by mid-summer McClellan found himself outmaneuvered by Lee, who turned out to be a more adroit student of the previous war.

Grant and Lee both learned valuable lessons in Mexico. While commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee was known for his audacity, his willingness to divide his army in the face of superior numbers and his masterful execution of flank attacks at places like Gaines Mill and Chancellorsville. It was in Mexico that Lee learned to be bold while reconnoitering battlefields for Scott, and at Cerro Gordo and Contreras he charted the path for decisive flank attacks against Mexican forces. Grant served under both Taylor and Scott, and while he adopted Taylor’s persona of casual attire, it was from Scott that he learned the art of military campaigning. During the Mexico City Campaign, Grant observed Scott’s skillful collaboration with the navy, which likely informed his decision making when partnering with naval assets on the Tennessee River in 1862 and the Mississippi River in 1863. As a young subaltern, Grant also witnessed Scott’s bold move in severing his supply line back to the coast and making his final push to Mexico City while living off the land. One wonders how this might have influenced Grant’s march through Mississippi or William T. Sherman’s march to the sea. Even though Sherman was not in Mexico, he knew its battles and campaigns and conducted his famous march with the approval of Grant. Furthermore, since Grant was a quartermaster officer in 1846-1847, he was familiar with the skills necessary for an army to subsist in the field.

Civil War commanders also learned valuable lessons in Mexico about the use of artillery, the complications of invading and occupying hostile territory, the difficulties of navigating civil-military relations and the superiority of offensive tactics. The cause-and-effect relationship between these two wars has never received adequate attention as Civil War biographers often treat the former war as a minor prelude to the latter, more important war. Since Civil War generals rarely referred to their observations and experiences in Mexico as justification for command decisions in the 1860s, it is sometimes easier to infer than to document such connections. However, a close study of the first war makes some connections obvious and others likely with the examples offered in this essay being just a sampling. It is certainly incumbent on the Civil War enthusiast to give more attention to war with Mexico and consider the lessons learned below the Rio Grande that would later inform Civil War generalship.

Timothy D. Johnson is the author of The Mexican-American War Experiences of Twelve Civil War Generals from LSU Press. He is currently the Elizabeth Gentry Brown Professor of History at Lipscomb University in Nashville and has authored or edited over two dozen articles and seven books on 19th century military history, dealing primarily with the Mexican-American War. Most significant among them are his biography of Winfield Scott (1998) and his account of the 1847 Mexico City Campaign (2007), both published by the University Press of Kansas. In 2018, The University of Tennessee Press published his most recent book, For Duty and Honor: Tennessee’s Mexican War Experience.

Timothy D. Johnson is the author of The Mexican-American War Experiences of Twelve Civil War Generals from LSU Press. He is currently the Elizabeth Gentry Brown Professor of History at Lipscomb University in Nashville and has authored or edited over two dozen articles and seven books on 19th century military history, dealing primarily with the Mexican-American War. Most significant among them are his biography of Winfield Scott (1998) and his account of the 1847 Mexico City Campaign (2007), both published by the University Press of Kansas. In 2018, The University of Tennessee Press published his most recent book, For Duty and Honor: Tennessee’s Mexican War Experience.