“Fierce skirmishing erupted as Pike’s forces landed. Supported by covering fire from Chauncey’s ships, the Americans gradually pushed the British and militia back.”

IN THE SPRING OF 1813, as the War of 1812 raged on, the young United States sought to strike a major blow against British forces in Upper Canada. American military planners set their sights on York (present-day Toronto), the capital of the province and a symbolically important target. Maj. Gen. Henry Dearborn, commander of the U.S. forces along the northern frontier, and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, head of the U.S. Navy on Lake Ontario, orchestrated a joint operation to capture the town. For the struggling American war effort, a decisive victory was badly needed to regain momentum after setbacks in earlier campaigns.

York was lightly defended. British forces under Maj. Gen. Roger Hale Sheaffe had just a few hundred regulars of the 8th (King’s) Regiment of Foot, about 300 militia, and a handful of indigenous warriors allied with the Crown. While the town was small and lacked heavy fortifications, it did contain the Provincial Marine’s shipyard, stores of supplies, and a nearly-completed warship, the HMS Sir Isaac Brock — all tempting prizes for the Americans. Additionally, the political importance of capturing the provincial capital made York an attractive target beyond its immediate strategic value.

On April 25, 1813, Chauncey’s fleet set sail from Sackets Harbor, New York, carrying about 1,700 troops under Brig. Gen. Zebulon Pike, the famous explorer-turned-soldier who had previously led expeditions into the American West. The troops, many of them regulars with limited combat experience, were eager to redeem the reputation of the U.S. Army after previous defeats. The fleet consisted of schooners, sloops, and brigs, hastily armed and adapted for military service.

By dawn on April 27, the fleet arrived off York. Amid heavy winds and rough water, Pike’s men clambered into small boats and rowed ashore west of the town. The landing site, now known as Sunnyside Beach, was chosen to avoid the heaviest concentrations of enemy forces. British and indigenous defenders, caught off guard, mounted a spirited but disorganized defense along the beaches. Sharpshooters fired from behind trees and rocks, and small groups of warriors launched sudden, fierce attacks.

Fierce skirmishing erupted as Pike’s forces landed. Supported by covering fire from Chauncey’s ships, the Americans gradually pushed the British and militia back. Sheaffe, realizing his vastly outnumbered troops could not hold, ordered a retreat toward the town’s east side, abandoning Fort York and its critical storehouses. Attempts to rally local militia units largely failed, as many townspeople fled or surrendered without fighting.

In a desperate effort to deny the Americans a key prize, Sheaffe ordered the destruction of the fort’s powder magazine. As Pike and his men advanced through the ruins, the magazine exploded in a thunderous blast that shook the entire battlefield. The explosion killed or wounded more than 250 American soldiers, including Pike himself, who was fatally injured by falling debris. The general, mortally wounded but still conscious, reportedly urged his men to “Push on, brave fellows, and avenge your general.”

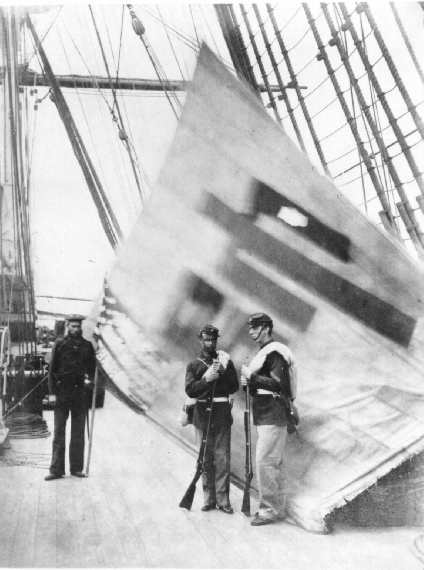

The loss of Pike was a severe blow to American morale. Nonetheless, the Americans pressed their advantage. By early afternoon, York had surrendered. Sheaffe and most of his regulars had escaped eastward, but American forces took hundreds of prisoners, captured artillery, destroyed military supplies, and seized or burned ships under construction at the dockyard. Among the spoils were cannons, ammunition, and the disassembled frame of the HMS Sir Isaac Brock.

However, discipline among the American troops soon collapsed. In the days following the capture, widespread looting and arson ravaged York. Government buildings, including the Parliament House, were torched, destroying public records and symbolically humiliating the British authorities. Private homes and businesses were not spared either, and reports of plundering further tarnished the American victory. These acts would later be cited by the British as justification for their own burning of Washington, D.C. in 1814.

The behavior of the American troops deeply embarrassed senior commanders. Although Dearborn issued orders to restore discipline and punish offenders, enforcement proved weak. Public opinion in the United States remained divided; while many celebrated the conquest, others criticized the conduct of the troops and mourned the loss of one of the nation’s rising stars in Pike.

Though the strategic value of York was limited, the victory provided a badly needed boost to American morale. It marked one of the first successful large-scale amphibious assaults in U.S. military history, showcasing the potential of joint army-navy operations. It also demonstrated the importance of controlling the Great Lakes, where shipbuilding races and naval supremacy would continue to shape the conflict’s outcome.

Yet the death of Zebulon Pike, a national hero, cast a long shadow over the triumph. Pike’s death inspired a wave of mourning across the United States. Tributes and memorials sprang up in his honor, and he was hailed as a martyr to the cause of American expansion and honor.

In the end, the capture of York in April 1813 was a moment of both glory and controversy. It underscored the ferocity of the conflict in the Great Lakes region, the difficulties of maintaining discipline among volunteer troops, and the high cost of war — lessons that would echo throughout the remainder of the War of 1812. The ashes of York and the memory of Pike’s sacrifice would linger in the minds of both Americans and Canadians, becoming part of the larger story of a war that, though often overshadowed by other conflicts, helped define the future of North America.