“Controversy dogged his every step.”

By Jacqueline Reiter

SIR HOME POPHAM was one of the more underappreciated characters involved in the British fight against revolutionary and Napoleonic France.

He was a post-captain in the Royal Navy from 1794 to 1814, yet he played a surprisingly prominent part in the formation of British global and imperial strategy during the period. He did this in part by becoming an expert in amphibious operations, and by tackling the murkier, less straightforward jobs others might have hesitated to take on.

But Popham also realized what the politicians at home wanted to hear, and he gave it to them. They lapped it up, and Popham was rarely unemployed, although controversy dogged his every step.

Popham was born in 1762, probably in Gibraltar, the younger son of the British consul to the Moroccan city of Tetouan. Originally destined for a legal career, he joined the Royal Navy in 1778 in a hurry when his elder brother and guardian fled to India to escape his debts.

For eight years young Home had a reasonably normal naval career, rising to the rank of First Lieutenant. But in 1786, faced with prolonged unemployment, Popham left the Navy, hired a merchant vessel, and engaged in private trade in the East. This meant undercutting the East India Company trade monopoly in the area, but Popham didn’t care — at least until his merchant vessel was captured in 1793 by HMS Brilliant as a prize of war.

At a loose end, Popham petitioned the Admiralty to be reinstated on the list of lieutenants. Amazingly, the navy agreed, but appointed him agent for transports to Ostend, normally a dead-end job. Popham, however, made himself an expert on amphibious operations and became indispensable as the British retreated across boggy, river-crossed territory into Germany. By 1794 even the Duke of York, in command of the British forces, knew his name. York secured Popham’s promotion to post-captain that same year – without a ship, but a reflection of Popham’s importance. Popham cemented his reputation by helping evacuate the British army safely back to England over 1795 and 1796.

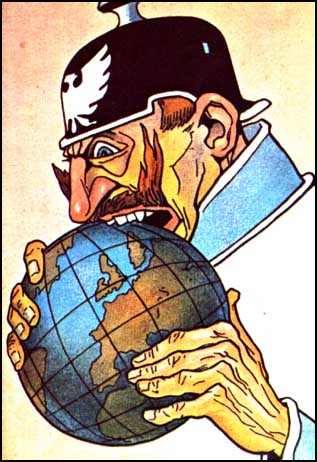

The Secretary of State for War, Henry Dundas, now became Popham’s main political patron and employer. Dundas was Prime Minister Pitt’s right-hand man and a firm supporter of “blue-water” strategy, or the idea that Britain could only win the war by expanding her colonies at France’s expense. Popham quickly cottoned onto this and proposed a variety of schemes in the Indian Ocean to defend British trade routes and what he referred to as “the golden object” of India, the centre of Britain’s growing empire.

Through Dundas, Popham was employed in a variety of guises, not just as an amphibious expert, but also as an unofficial diplomat, as an authority in experimental weaponry, and as a planner of expeditions. These expeditions did not always succeed, but impression was just as important as long-term effect. So long as Popham could help show France Britain was no pushover, the politicians continued listening to his plans.

Perhaps Popham’s most infamous exploit, however, was his unauthorised expedition to Spanish South America in 1806. Popham had been sent to re-capture the Cape of Good Hope from the Dutch, but after this he grew restless. After dusting off an old, but firmly shelved, plan he had proposed to Dundas to redirect South American wealth from Spanish into British pockets, he persuaded the British military commander at the Cape to give him 1,500 men to invade the Rio de la Plata. Despite capturing Buenos Aires, nearly the whole British military force was itself captured when the locals rose against their conquerors. Popham returned home to a court-martial. He was found guilty of attacking Buenos Aires without orders, but, astonishingly, was only “severely reprimanded.” Within months he was employed again, as Captain of the Fleet – a senior post – at the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807.

Still, Popham had outlived his usefulness. His old patrons were out of office or dead; after his court-martial, Popham found it more difficult to attract the attention of the new generation of politicians. The last expedition he helped plan, to Walcheren in 1809, was a disaster, thanks in part to outbreaks of malaria and typhus that killed thousands of British troops.

Popham did get one last hurrah in 1812, when a new First Lord of the Admiralty sent him to liaise with the Anglo-Allied army under Wellington off the northern Spanish coast. Popham’s frequent raids along the coast tied down several thousand French who might otherwise have turned the tide at the Battle of Salamanca in July 1812. Apart from this, however, Popham’s diplomatic relations with the Spanish guerrillas were a disaster and he was not employed again during the war.

He eventually became naval commander-in-chief of the Jamaica station in 1817, but two of his children died there and his own health was ruined. He died of a stroke in September 1820, a few weeks off his 58th birthday.

Popham’s sudden death ended an uneven, but important, career. Still, his main legacy did not grow out of his military plans or diplomatic forays: Popham devised a telegraphic signalling code that was officially adopted by the Royal Navy in 1816 and remained in use all the way into the 20th century. Popham may have missed the battle of Trafalgar, but Nelson’s famous signal, “England expects that every man will do his duty”, was sent using Popham’s code. Popham would not have been ashamed – although, given the variety of activities in which he was involved, he might have been surprised – to know his code became his gift to posterity.

Jacqueline Reiter is the author of Quicksilver Captain: The Improbable Life of Sir Home Popham. A PhD from the University of Cambridge in 2006, her first book, The Late Lord: the Life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (Pen and Sword, 2017), illuminated the career of Pitt the Younger’s elder brother. Her articles have appeared in History Today and the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research; she has written for the History of Parliament and co-written a chapter with John Bew on British war aims for the Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars.

Jacqueline Reiter is the author of Quicksilver Captain: The Improbable Life of Sir Home Popham. A PhD from the University of Cambridge in 2006, her first book, The Late Lord: the Life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (Pen and Sword, 2017), illuminated the career of Pitt the Younger’s elder brother. Her articles have appeared in History Today and the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research; she has written for the History of Parliament and co-written a chapter with John Bew on British war aims for the Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars.

1 thought on “Sir Home Popham — Inside the Chequered Career of One of the Royal Navy’s Most Interesting Figures”