“The world’s first military airlift was known as ‘the Hump’ for both the 15,000-foot mountains the air route crossed and the extreme burdens the mission placed on the young men of the U.S. Army’s Air Transport Command.”

By Rory Laverty

ICE ENVELOPED Thomas Sykes’ cargo plane somewhere over northern Burma. It frosted the wings and windows and clogged the carburetor intakes until the engines began to cough. Gale-force headwinds hit them next and dropped their airspeed a hundred miles an hour. The pilots fought the controls to keep the ship out of freefall, but when they turned, a crosswind caught the wings and flipped them sideways.

“Suddenly we were on our back,” Lt. Sykes said. “While hanging in my safety belt and with dirt from the floor falling all around, I realized it would be impossible to bail out.”

The C-47 completed the roll before he could try. The beleaguered air crew, surprised to be alive, struggled to catch their breaths. They began to regain altitude, but wind gusts pummeled them unpredictably, and most of the instruments were now frozen and useless. The crew had no communications with the ground or other planes, no radio signals from homing beacons, no working radio compass or LORAN navigation system, and no view out the cockpit windows. They did have a hand compass, a working altimeter, and an airspeed indicator – but no idea where they were on the China-Burma-India map.

They only knew that they were about to run out of gas. They had to bail out, but they didn’t know where they were and they dreaded jumping into a raw jungle the size of Texas, full of man-eaters, head-hunters and Japanese soldiers with bayonets. Only thing worse would be to jump anywhere near Namjagbarwa, a 21,000-foot Himalayan peak to their north that was surrounded by frigid glacial lakes. If they parachuted into that tank, they might freeze to death before they could drown.

As their last drops of gas turned to vapor, the crew’s Maydays were met with static. Finally, Sykes made the call: They would bail out before they ran out. He set the auto-pilot and the location transmitter. The crew pulled on their parachute-packs and shuffled grimly to the side bay.

Just before the first crewman received the signal to jump, the cloudbank fractured, and a seam opened in the heavy cotton. The plane steered into it, slid down thousands of feet and emerged in clear air, within sight of familiar landmarks.

As they limped back to their base, the airmen saw other planes headed into the storm.

Hours earlier on that day, Jan. 6, 1945, a Siberian cold front drove south through China, icing the eastern Himalayas from the Mekong pass to the headwaters of the Brahmaputra. In those same early hours, humid easterly winds billowed across the Bay of Bengal onto shore in India, where they rippled the rice paddies and steamed north into the broad jungle valleys. The two fronts played chicken that afternoon over Burma’s great gorges. In the evening, the storms merged and electrified into a cataclysm of cumulonimbus.

The Hump pilots never saw it coming. They were stationed a couple hundred miles west, in the lower Brahmaputra River valley in Assam, India, where their route was to fly east into Burma (now Myanmar) and then traverse the Patkai Mountains of the eastern Himalayas into China, where they would drop their plane’s load, refill their gas tanks and stomachs, and race the sunrise back to India.

Regardless of the weather, or the presence of Japanese fighter planes, the pilots had no choice: when called, they flew. Every other night, for months on end. To refuse to fly could mean a court-martial, so they got up and strapped in. More experienced pilots preferred to fly at night, when there was often less cloud cover and fewer storms. It was a 10-hour round-trip if everything went perfectly, which it almost never did.

Each cargo plane carried several tons of supplies, usually high-octane aviation gas, destined for Chiang Kai-shek and his Chinese nationalist armies (and Allied air forces) fighting Japan in east Asia. Despite seven years of horrific losses on the battlefield to better trained, combat-hardened Japanese forces – seven years of an Imperial holocaust and occupation that claimed as many as 15 million Chinese lives – Chiang and free China had survived by pulling back to a handful of provinces in the south, with their backs against the Himalayas. The Chinese nationalists were not thriving, but they were still ticking, and their last remaining supply lifeline was American lend-lease, sent by air from India.

The world’s first military airlift was known as ‘the Hump’ for both the 15,000-foot mountains the air route crossed and the extreme burdens the mission placed on the young men of the U.S. Army’s Air Transport Command, sent into the farthest reaches of a cursed and forgotten theater of World War II. They fought extreme terrain, horrific weather and a gauntlet of Japanese fighter planes and ground fire to keep a million Imperial troops fighting in China, instead of on Pacific islands and atolls against American sailors, soldiers and Marines.

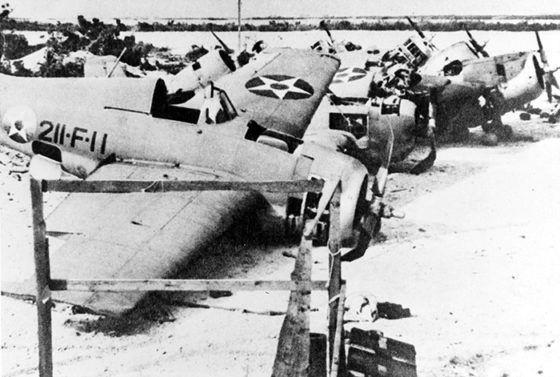

Nearly 600 Allied planes crashed during the Hump airlift. A third of the more than three thousand American pilots who flew there between April 1942 and August 1945 were killed or went permanently missing. Their crash sites formed an aluminum trail through the Burma jungle that their successors used for sight navigation.

The young and efficient commander of the airlift in 1945, William Tunner, whiffed on the storm of Jan. 6. The general’s weather reconnaissance pilots, known as ‘balloon blowers,’ missed the signs, and the synoptic-flight data analysts who read reports of wind speed, temperature, and air pressure saw nothing to merit an alert. So, Tunner did not know that somewhere over the great gorge of the Irrawaddy River in Burma, two kinetic fronts from Siberia and Bengal had locked horns with fury, and their collision fused a winter typhoon that was taller than Mount Everest and as broad as the horizon.

The hundreds of young American airmen aboard dusk-departing cargo planes were ignorant of the monster awaiting them, but they had no illusions about the risks of their endeavor. Hump flight hours counted as combat time for good reason. That night the Americans were piloting their standard, buggy C-46s and some temperamental new C-87s, as well as some reliable old C-47s that they called Gooney Birds. American balloon blowers, air commandos, and fighter pilots from the 10th and 14th Air Forces were also in the skies in a mismatched flock of smaller planes.

With more than a hundred aircraft aloft, pilots and radiomen began to warn of severe weather. Next came the Maydays, and some So Longs. Soon it was a chorus.

Pilot Murray Scott, who flew that night, heard a Mayday call on the radio: “I seem to be lost, and there’s six inches of ice on my control surfaces. We can’t hold height, so we’re bailing out now. So long.” Scott reported that “the pilot spoke calmly, as if he was going down to the corner store for cigarettes. We didn’t hear him again.”

The 10th Weather Squadron flew back up that night and reported some of the worst weather readings ever in the China-Burma-India theater. Ice frosted the entire upper Hump route, six-inches thick in places. Dense overcast extended from the ground to 30,000 feet. Winds were a steady 120 miles an hour with gusts up to 150, and up- and down-drafts were measured at 5,000 feet per minute. It all just kept getting worse.

Of the 30,000 combat hours American airmen flew during the 42-month airlift, the deadliest 24 were between noon Jan. 6 and noon Jan. 7, 1945. In that time, at least 15 planes crashed or disappeared: nine U.S. Army Air Transport Command cargo planes, three of Chiang’s China National Aviation Corporation planes, and three other aircraft from the U.S. Army 10th and 14th Air Forces. Eighteen airmen were killed, plus at least nine passengers. Some of the planes were blown so far off course their crash sites were never identified.

Bob Binzer had already built a long and varied Hump career when he became one of the pilots who bailed out on the night of a thousand Maydays. After many near-misses, he was not surprised when he finally had to yank his ripcord.

Lt. Binzer was among a minority of Hump pilots who still flew with a regular plane and crew in 1945 due to his specialized route tree among the Chinese bases. His trusty old C-47 was named The Able Queen, with Binzer in the left seat, Warren Elliott as co-pilot, George Youngling as engineer, and Dan Anderson as radio operator.

The pilots knew before takeoff on the night of Jan. 6 that they would be flying into trouble, but they didn’t realize how bad it would get. Cumulus clouds blocked their view of the Chinese ground. Binzer had requested extra gas at the base when he heard about bad weather, and they had been granted enough gas for six hours of flying on a route that normally took four hours. Near the Burma border they tried to ascend over the storm, clambering all the way up to the plane’s ceiling at 22,000 feet, but even that wasn’t high enough for clarity.

Conditions worsened. The crew tried every cowboy technique they could think of to conserve gas, slowing their intake to a trickle. The plane had stopped receiving radio calls from other pilots or transmissions from homing beacons. To the airmen, these were signs that they were at least a hundred miles off course, probably to the north, which turned out to be accurate.

The Able Queen was lost in unincorporated Chinese territory, flying against a great river of wind. At times the airspeed indicator showed the plane was in stasis or even moving backwards. They would ultimately squeak almost nine hours of flight out of what was considered six hours of fuel, but it wouldn’t be enough.

As they drew down their final minutes of gas, Binzer made the call for his crew to bail out. He told the men his decision and then activated the autopilot, location transmitter, and Mayday repeater. The pilots tore up any papers that could be useful to the enemy and pocketed medical supplies, flashlights and food. They decided to leave behind the Tommy gun and its case of ammunition.

The crew put on their parachute packs, clipped in their shoulder-holstered .45s, and double-knotted their boots before they lined up at the side bay. When the pilot flipped on the red jump signal on the wall of the compartment, they began to dive into space – each man five seconds after the last so they might land in proximity.

Youngling, the engineer who jumped second, pulled his ripcord too early. His parachute opened before he was out the door, which sucked him back into the plane. He threw himself out again in desperation, and though his body skirted the plane’s tail, his half-open parachute did not. It tore on the rudder and only partially opened as he fell, so Youngling descended much more quickly than the others and crashed down hard, injuring his back. He was miles from his crew.

Binzer’s turn came last, after Elliott. Facing the open side door and howling wind, he was mostly afraid of coming down in Lake Dianchi near Kunming, or in the fjords of Namjagbarwa, which the Americans called Mt. Tali. He counted to five and jumped; waited a few seconds to get clear of the tail; and then pulled his ripcord. “I was between two layers of clouds,” the pilot wrote. “I couldn’t believe how quiet it was.” He floated down easy as the Able Queen, free of all worldly burdens, droned off into the darkness.

The men touched down in a then-independent territory of the Tibetan prefectures, 150 miles south of Kweiyang. The mountainous region was sparsely forested and populated, and because of its remoteness it was uncontested by the various nations making war in East Asia.

The three able airmen found one another within hours along the area’s only dirt road. Only Youngling was missing, and the crew didn’t know if he was dead or alive. They went to nearby huts to ask for help, but it was night, and the locals were afraid of them.

By morning, others were curious about the tall, strange hominids who had floated down from the heavens. No one there spoke any English or Chinese, but the airmen fascinated the local kids, and by afternoon the entire village of 50 or so had gathered to watch and laugh at their every move.

A nearby man who spoke Chinese was summoned, and he communicated with the airmen in pidgin and hand gestures. They gathered that a nearby family had found Youngling prone on the roadside, injured but alive, and taken him in. That afternoon the Samaritans brought the flight engineer to the village, where he rejoined the other lost sons of the Able Queen. The relieved airmen celebrated for a night at a Chinese Army outpost and then hitched a two-day truck ride back to the 14th Air Force forward base at Kweiyang.

Binzer was back in the cockpit by the end of the week.

Rory Laverty is the author of Aluminum Alley: The American Pilots Who Flew Over the Himalayas and Helped Win World War II. A journalist who has written for The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Newsweek and The Oakland Tribune, he has reported on police and law enforcement, the military, and the justice system for a variety of publications since 1998. He lives in Wilmington, NC, and teaches at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Rory Laverty is the author of Aluminum Alley: The American Pilots Who Flew Over the Himalayas and Helped Win World War II. A journalist who has written for The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Newsweek and The Oakland Tribune, he has reported on police and law enforcement, the military, and the justice system for a variety of publications since 1998. He lives in Wilmington, NC, and teaches at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

It was an amazing feat to pull off. It’s just sad we lost so many.