“For decades, the entire incident remained shrouded in mystery.”

By Marc Liebman

BY NOVEMBER 1952, the air and ground war in Korea had been raging for two years and five months. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) had committed hundreds of thousands of soldiers to help their North Korean allies.

Four Soviet air force fighter divisions of the 64th Fighter Aviation Corps — 28th, 50th, 151st, and 324th Fighter Divisions — deployed to air bases People’s Republic of China near the mouth of the Yalu River on the western edge of the peninsula. Equipped with state-of-the-art MiG-15s, they were there to support the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) as well as the PRC’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Almost every day, Soviet MiGs engaged F-86 Sabers from 4th, 18th and 51st Fighter Interceptor Wings over the mouth of the Yalu River on the west side of the Korean Peninsula

On the ground, the war had stalemated to a line almost identical to the current border between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea).

In the Yellow Sea, planes from Task Force 95 made up of Royal Navy, Royal Australian Navy and U.S. Navy escort carriers flew interdiction and close air support sorties while their U.S., Royal Navy, Canadian Navy, and Australian Navy escorts provided naval gunfire support.

In the Sea of Japan, the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 77 roamed up and down the coast. Generally, its carriers and escorts launched close air support and interdiction strikes a from within 50 miles of the coast to cut off supplies to the PLA and what was left of the KPA.

When the war started, the USS Valley Forge (CV-45) was rushed to Korean waters; its air wing flew its first American airstrikes of the war on July 3, 1950, just eight days after KPA troops entered South Korea. By 1952, the Navy was rotating the three Essex-class carriers it had in theater so two carriers were on station off the east coast of Korea with a third refitting/rearming in Japan.

On November 18, 1952, the USS Oriskany (CV-34) was off the northeast coast of North Korea about 50 miles east of Chongjin and less than 100 miles southwest of the Soviet air and naval bases at Vladivostok.

The carrier and its Air Group 102 had been on station since October 1952. Chongjin was a hub for roads and railroads from the PRC and Vladivostok in the Soviet Union that allowed supplies to flow to the KPA and the PLA. Air Group 102’s pilots roamed northeastern North Korea on armed road reconnaissance missions during which they strafed convoys and trains as well as flying bombing missions to destroy bridges on the road and rail lines.

On board Oriskany, the task force commander received a top-secret message indicating that MiGs were expected to fly south from Vladivostok and over Task Force 77. Standard U.S. Navy doctrine was then, and is today, to intercept any intruder before they reach their weapon launch envelop and escort them until they depart.

The weather that day was terrible. On top of the heavy snowfall that blanketed Task Force 77’s ships, the air temperature was in the 20s and the water temperature was in the mid-thirties.

Without an exposure suit in 30-degree water, a pilot has about two minutes or less to get into his raft before the cold immobilized his body. Once in his raft, he still could die from exposure.

Without an exposure suit in 30-degree water, a pilot has about two minutes or less to get into his raft before the cold immobilized his body. Once in his raft, he still could die from exposure.

Lieutenant Royce Williams, a Naval Reservist and three other from VF-781 manned their F9F-5s and launched at 1300. Once in the air, flight leader Lieutenant Elwood developed fuel and hydraulic problems. He and his wingman were ordered back to the carrier. Williams and his wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade John Middleton, were now alone.

Williams, a native of Wilmot, South Dakota, was a corporal in the Minnesota National Guard before transferring to the Navy to attend flight school. He earned his wings on November 15, 1945, too late to see combat in World War II. After completing his tour of active duty, he joined VF-781, a Naval Air Reserve squadron flying F4U Corsairs from NAS Alameda.

Dogfight!

Williams’ flight was soon vectored toward a group of MiGs that was detected on radar roughly 80 nautical miles north-northeast of the task force.

The two F9Fs broke out in the clear at 12,000 and were climbing past 16,000 feet when Williams spotted the enemies’ contrails, 45 miles from the carrier. He estimated the Soviet fighters to be above 30,000 feet higher.

Williams kept climbing and radioed to the Oriskany that he had a “tallyho” on the MiGs which were split into a three plane and a four plane sections. Both were now diving on the two F9Fs from different directions.

The CIC on board Oriskany radioed Williams not to engage when suddenly the MiGs opened fire with their 23mm and 37mm cannon.

With tracers streaming past his F9F-5, Williams replied as he made sure his cannon were armed and ready to fire. “We are already engaged!”

Both Middleton and he fired a short burst at a MiG. Pieces flew off the Soviet fighter and the fighter began to smoke as it dove past. Middleton followed the damaged MiG down to finish it off but couldn’t; all four of his plane’s 20mm cannon jammed. Williams ordered Middleton to fly back to the Oriskany

Williams was now alone in a dogfight against six MiG-15s, each of which had an 80-knot advantage in level flight over his aircraft and a much higher rate of climb. The Soviet MiGs were now rocketing above Williams to make another diving pass. For Williams, a vertical fight was one he knew he would lose. Each time a MiG got on his tail; he rolled the F9F into a tight turn forcing the MiGs to overshoot.

The six MiGs swirled around Williams’ Panther. As one crossed in front of him, he fired an almost 90-degree deflection shot. The rounds hit home as chunks came off the MiG. The pilot ejected.

Williams, his head on a swivel, continued to dodge the MiGs. Another passed below him and pulled up in front of his F9F. Williams instinctively moved the controls to put the pipper of the gunsight on the enemy and pressed the trigger. His four 20mm cannon spoke and the MiG-15 exploded.

Several turns later, another MiG-15 dove straight at Williams who rolled out of a turn and climbed to meet the threat. The longer ranged cannon on the MiG allowed its pilot to fire first but the shells passed below the F9F. Once in range, Williams fired and could see flashes from his 20mm shells hitting the MiG. It went straight down, smoking. Williams’ guns suddenly fell silent; he was out of ammo.

Williams dove for the clouds whose tops were at about 12,000 feet, hoping to get away. The remaining MiGs chased his diving F9F, their guns blazing. A 37mm shell hit in the accessory section of the American jet’s engine. The explosion severed Williams’ rudder cables and knocked out his hydraulics, leaving him with limited elevator and aileron control.

A barrage of 23mm cannon shells were fired at Williams’ F9F. Several hit his jet as he used the elevator to porpoise the fighter erratically to dodge the MiG’s shells. Once in the clouds, Williams now had to fly the airplane on instruments. Free of the MiGs, he descended until he broke out below the clouds at just 400 feet.

Dwindling fuel wasn’t Williams’ only problem; below 170 knots, his jet was uncontrollable. The normal landing speed for an F9F was about 120 knots. Bailing out wasn’t an option; ejecting into the 37 deg. F water meant certain death.

Flying a conventional turning approach to the back end of the carrier was not possible, given his lack of control. After learning of Williams’ predicament, the captain of the Oriskany turned the ship so the Panther could make a straight in approach. Williams was able to set down on the deck and catch a three wire.

When the squadron’s mechanics inspected his F9F, they found 263 holes in the fuselage and wings made by cannon shells and shrapnel. The Panther was a total loss.

Classified

Safely aboard, Williams debriefed with the task force and air group intelligence officers who told him that he could not discuss the dogfight, now classified Top Secret, with anyone unless he had Navy approval.

The official cruise report credited Williams with two kills and two probables. Middleton was given a probable in the fight. Both planes’ gun camera footage was immediately taken by the intelligence officers and later, Williams learned, was passed along to the newly formed National Security Agency.

For decades, the entire incident remained shrouded in mystery. Over the years, pieces of the story began to emerge, yet Williams, although long since retired, refused to discuss the dogfight. Then in 1992, the Soviet Union collapsed. With the Cold War at an end, Russia’s government finally released the names of four pilots — captains Belyakov and Vandalov, and Lieutenants Pakhomkin and Tarshinov — who died that day.

Other unconfirmed reports surfaced that the Soviet’s lost six airplanes in the encounter. A fifth crashed in Soviet territory as it was limping home. Another aircraft and pilot were listed as MIA because the plane never returned to its base. All six were members of Soviet Naval Aviation.

We now know the message to the USS Oriskany warning of the MiG flight came from a National Security Agency (NSA) team on board the heavy cruiser USS Toledo (CA-133). More than likely, the intelligence that was used to launch Williams came from a communications intercept. At the time, the mere existence of the newly formed NSA was still considered Top Secret which earned it the moniker “No Such Agency.”

Royce Williams flew a total of 70 missions during the Korean War and stayed on active duty. His distinguished career included command of VF-33 and then, during the Vietnam War, commander, Carrier Wing 11. During his Vietnam deployment as the “CAG”, Williams flew 110 missions. He retired as a Captain, (O-6) in 1975.

On the USS Midway, now a museum ship in San Diego, there sits an F9F Panther with the silhouettes of four MiGs on the side under the cockpit. It’s a tribute to Williams. Assuming he shot down five and Middleton one, Royce Williams qualified as an ace. There is a movement, sponsored by a U.S. Senator and several Navy flag officers to have Williams awarded the Medal of Honor for the dogfight.

Explaining Williams’ victory

So, how did Royce Williams defy the odds and prevail in a fight against half a dozen front-line Soviet MiGs?

For starters, he was able to use the F9F’s superior turning ability to force the Soviet pilots to use slash and dash tactics that he could counter with sharp turns.

Also, gunnery training proved decisive. Williams, like other Navy fighter pilots of the era trained in the Second World War, where he learned to instinctively maneuver his airplane into a firing position. The lead computing gunsight on the F9F and the accuracy of the 20mm cannons did the rest.

Finally, credit must also go to the ruggedness of the F9F. Time and time again in Korea, F9Fs were damaged by enemy fire and more often than not, the airplane brought the pilot back to the carrier.

Marc Liebman is a retired Navy Captain and Naval Aviator and the award-winning author of 11 novels, five of which were Amazon #1 Best Sellers. He is also a military historian and speaks on military history.

SIDEBAR:

MiG-15 vs. F9F Panther

By Marc Liebman

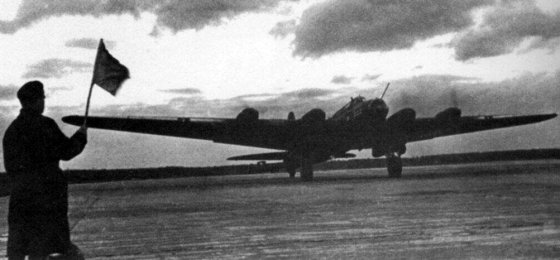

MiG-15

The MiG-15 was the first swept wing fighter made by Mikoyan-Gurevich. NATO gave the plane the code name Fagot. Its designers took advantage of technology the Soviets captured at the German Focke-Wulf factory in 1945. The drawings, wind tunnel models and test data for the proposed Focke-Wulf TA-183 jet fighter were of particular interest to Russian aircraft designers. It’s no surprise that the MiG-15 looks very similar to the German TA-153, including its wing sweep of 35 degrees and cruciform t-tail that extends aft of the fuselage.

Early Soviet jet engines weren’t as powerful as Western designs and much to the Soviet’s surprise, Sir Stafford Cripps recommended the British Labour Government give the Soviets a license to build the Rolls-Royce Nene engine, a drawing package and several engines.

The first MiG-15 prototype, designated I-310, was designed to intercept and shoot down American B-29s, B-50s and later, B-36s. It first flew on Dec. 30, 1947, powered by a copy of the Rolls-Royce Nene.

The Soviet Air force chose to arm the MiG-15 with two 23mm and one 37mm cannon to maximize the damage it could do to a bomber. However, the two guns’ different ballistics hindered the fighter in air-to-air combat.

Unlike the armament on U.S. aircraft — .50 caliber machine guns or 20mm cannon – the shells from the MiG-15 began to diverge almost as soon as they left the barrel. While ideal for shooting down a bomber, the guns were not the best solution to hit a fast moving, maneuverable target.

Deliveries of MiG-15s to Soviet Air Force units began in 1948. MiGs, flown by Soviet Air Force pilots, saw combat in the later stages of the Chinese Civil War.

The first MiG-15 kill was of a Republic of China P-38 photo reconnaissance airplane on April 28, 1950.

Grumman F9F Panther

Immediately following the end of the Second World War, the U.S. Navy asked several aircraft manufacturers to develop a jet powered fighter to deploy on carriers.

The first was the twin-engine McDonnell F2H Phantom. It saw some service in Korea, but by then, the F2H had been supplanted by the better performing F9F-5 which first flew on Nov. 21, 1947.

Due to the need for slower landing speeds, Grumman chose a straight wing design for the F9F. To increase its fuel capacity because the large size of the centrifugal compressor on the Pratt & Whitney J-48, Grumman added tip tanks to the wings which not only increased fuel capacity but also increased the F9F’s roll rate.

It’s interesting to note that the J-48 was built under a license from Rolls-Royce and was a more powerful version of the Nene given to the Soviets which powered the MiG-15.

Grumman’s design, built by what Naval Aviators affectionately called the Grumman Iron Works, was 7,600 pounds heavier than the Mikoyan-Gurevich fighter. Coupled with the straight wing, the MiG was much faster and a had a much higher rate of climb.

The Panther, despite the differences in performance, had a better rate of turn and a could turn tighter. Its armament of four 20mm cannon, with 190 rounds per gun, had a higher rate of fire than the MiG’s two 23mm and one 37mm cannon. Unfortunately, in a dog fight with a fast-moving fighter, the slow rate of fire of the MiG’s armament put the fighter at a tactical disadvantage.

Despite the dramatic difference in performance naval aviators flying the Panther shot down seven MiG-15s for a loss of just two F9Fs. That is, before Nov. 18, 1952 engagement.

Marc Liebman is a retired U.S. Navy Captain and Naval Aviator and the award-winning author of 14 novels, five of which were Amazon #1 Best Sellers. His latest is the counterterrorism thriller The Red Star of Death. Some of his best-known books are Big Mother 40, Forgotten, Moscow Airlift, Flight of the Pawnee, Insidious Dragon and Raider of the Scottish Coast. All are available on Amazon here.

Marc Liebman is a retired U.S. Navy Captain and Naval Aviator and the award-winning author of 14 novels, five of which were Amazon #1 Best Sellers. His latest is the counterterrorism thriller The Red Star of Death. Some of his best-known books are Big Mother 40, Forgotten, Moscow Airlift, Flight of the Pawnee, Insidious Dragon and Raider of the Scottish Coast. All are available on Amazon here.

A Vietnam and Desert Shield/Storm combat veteran, Liebman is a military historian and speaks on military history and current events.

Visit his website, marcliebman.com, for: past interviews, articles about helicopters, general aviation, weekly blog posts about the Revolutionary War era, as well as signed copies of his books.

And for expanded videos of his MilitaryHistoryNow.com articles, subscribe to Marc’s Youtube channel.

Looks like the F9 was outclassed. The difference was the pilot and durability of the airframe.

That was the story with the Japanese Zero and many of the US fighters in WW2

In the very back of the Strategic Air Command Museum, just south of Omaha, NE — is a small room. The room is filled with photos of cold war aircrew and planes shot down by Red Chinese or Soviet Russians during the post 1945 period and beyond in the Cold War. All denied missions and denied actions. Those shot down and captured were denied by our State Department (aka the rat bastards).

One story that has never been told is just as classified and denied as this story of the Panthers and MiGs. From the end of WW2 to 1953 the US Army Air Corps and new-born USAF flew B-29 bombers on daylight and night time photo-reconnaissance missions over Red China near Korea and over Russia (near Korea and North of Japan). There was an entire Wing of B-29’s dedicated to this Recce mission and based out of Japan. Due to the Russians radar controlled AAA batteries and then the MiG-15’s every B-29 was shot down. 54 bombers with crews lost before 1953.

None of them are on the wall in the SAC Museum.

My Uncle was a photographic technician and gunner on one of those B-29’s. He died 6 years ago and he was the only survivor of his entire squadron. He hated the USAF and Hap Arnold for sending big slow airplanes up for the fast MiG-15’s to shoot down.

This story needs a book. I hope the author is up to it.