“The Dodecanese operations were just a sideshow, still not widely known in World War Two military history. Yet for those who served and died there, it was no sideshow; the cost was high on all sides.”

By Brendan O’Carroll

THE LONG RANGE Desert Group (LRDG) was one of the first ‘special forces’ of the Second World War.

Established by British officers under the direction of Major Ralph Bagnold, its founders were noted and experienced desert explorers, well qualified to launch such a force. The primary task of the LRDG was reconnaissance and intelligence gathering behind enemy lines in North Africa, and more so later, as raiders.

Specially selected members of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force served as the founding troops of the unit. They were soon followed by hand-picked soldiers from Britain and Southern Rhodesia.

As experts on desert travel and navigation, the LRDG was often tasked with guiding other units on their missions. Such as the Free French and Special Air Service (SAS) on their raids on enemy airfields. Also inserting, supplying and collecting small commando teams and undercover agents, plus recovering downed airmen.

The patrols were masters of behind the lines operations, such as mine laying, attacking road convoys and remote enemy outposts. Their greatest independent raid was in September 1942, against the Italian occupied town and airfield at Barce, where they shot up the garrison and town, attacked the airfield and destroyed and damaged many aircraft along with fuel and munitions dumps.

In their intelligence gathering role, their most significant task was the Road Watch. Where in 1942, the Tripoli-Benghazi road was monitored for nearly two months producing a detailed record for HQ in Cairo of all enemy traffic that passed in and out of the area. This was to assess the enemy’s strength prior to the Alamein battles and proved to be one of the LRDG’s most valuable operations.

In January 1943, an LRDG patrol were the first troops of the British Eighth Army to enter Tunisia. They found an uncharted pass through the hills which became known as Wilders Gap. Two months later the New Zealand Division used this route as a ‘left hook’ round the enemy’s fortified Mareth Line and this eventually lead to the defeat of the Axis forces in North Africa.

With the Allied victory in North African in May 1943, the LRDG had now “run out of desert.” They re-established themselves in the Cedars of Lebanon, to reform and train for a new commando-type role, while still operating as a reconnaissance and intelligence gathering force.

The patrols were reorganized into small self-contained units, varying from eight to 14 men, capable of maintaining communications over distances of 160 kilometres, while operating behind the lines on foot. This was a radical departure from earlier missions that famously saw the LRDG roll swiftly across the vast open spaces of North Africa by jeep and light truck. As such, the fitness requirements for the group was exceptionally high. Indeed, some desert veterans who were unable to make the transition, had to return to their original regiments.

The men of the new unit trained in mountain warfare, demolitions, skiing, the handling of pack mules and later parachuting. A number were also taught basic German and Greek, so they could seek the assistance of the local people when needed.

But as an independent force, they had to carry all of their supplies, including heavy radios and batteries, on their backs. This required exceptional physical robustness and fortitude.

Armed with these new skills, in September 1943, the LRDG received movement orders to progress to the Aegean Dodecanese Islands to undertake an island coast watch and intelligence gathering role.

Following the Italian armistice and capitulation of the fascist government under Mussolini in early September 1943, British forces from the Middle East began to occupy the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey. The Italians had claimed the territory since 1912, and while they were known as the ‘the Italian Islands of the Aegean,’ the population was mainly Greek. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, saw the takeover of the Dodecanese as, “an immense, but fleeting opportunity.” He cabled Middle East Command. “This is a time to play high,” Churchill wrote. “Improvise and dare.”

A plan was soon devised, which Churchill approved, called Operation Accolade. The objective was to tie down German forces in the eastern Mediterranean while the invasions of Sicily and Italy got under way. It was also hoped that the Italian troops who garrisoned the islands might even join the British against the Germans. Essential to the success of Accolade was the occupation of Rhodes, whose vital airfields were the key to the command of the Aegean. Furthermore, it was thought it seizing the islands might encourage neutral Turkey to join the Allies. Such a coup would allow the Allies access to a warm water route through the Dardanelles to the Balkans and Russia. Churchill had described the Allied advance into Italy as attacking, “the soft underbelly of Europe.” Going through the Dardanelles was similar thinking.

Americans war planners were sceptical. General Dwight Eisenhower considered Churchill’s plan a waste of time and resources and not a priority for the Allied forces at that point in the war. They were committed to the invasions of Sicily and Italy and resisted providing U.S. ships or aircraft to support a ‘sideshow’ that could be dealt with at a later opportunity.

Nonetheless, Churchill went ahead with his plan.

Click to enlarge

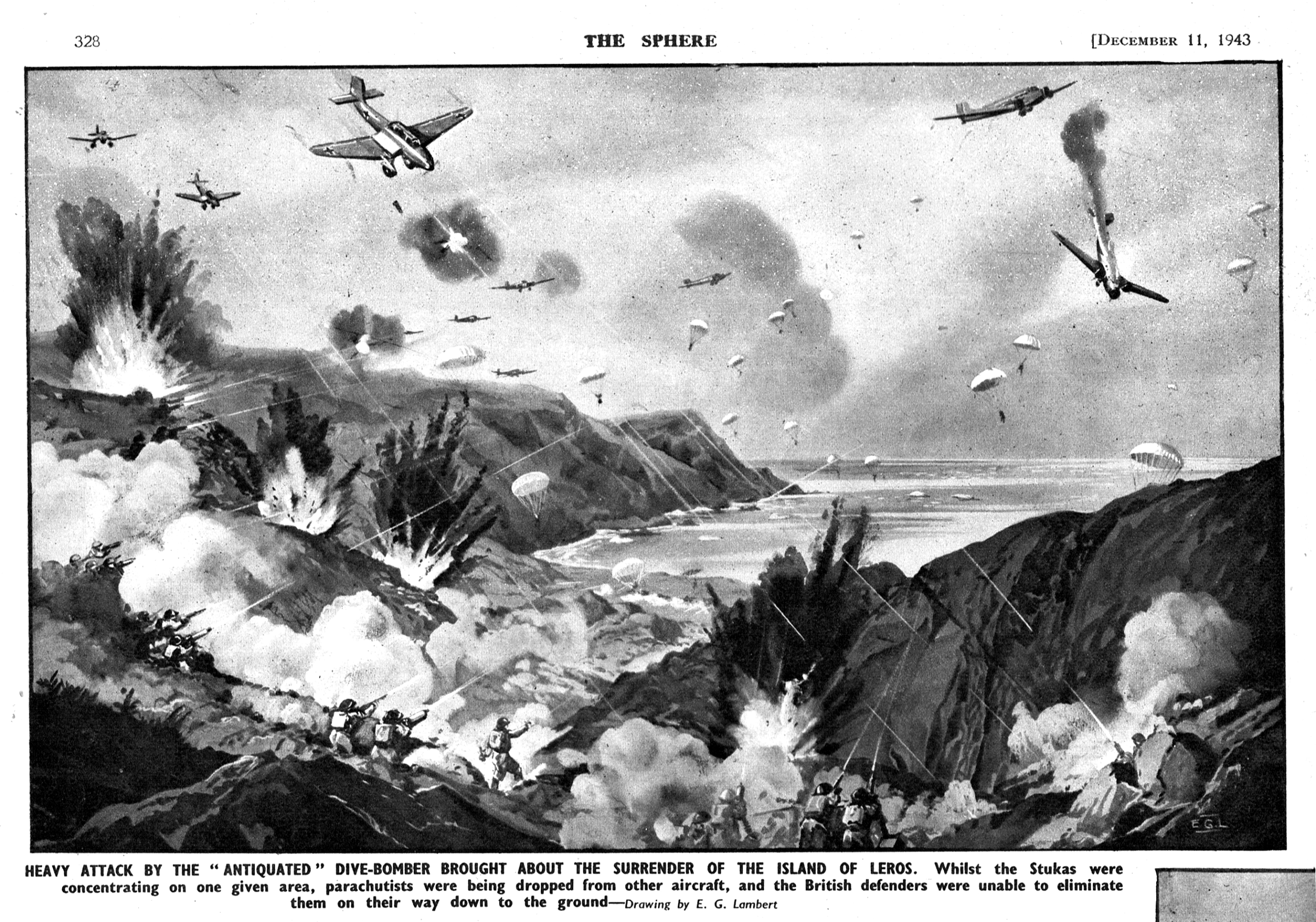

British forces landed on the island of Leros, where there was a good natural harbour, complete with a naval and seaplane base. Landings also took place at Kos – important because of its airfield – and at Samos, Symi, and Kastelrosso, as well as other smaller islands.

Where the British had established their forces, the Italians offered no resistance and, as hoped, soon turned against the Germans. For their part, the Germans were not idle and in early September quickly occupied Rhodes, before the British could gain a foothold there.

Rhodes of course was the strategic key to the Dodecanese. The German occupation immediately threatened the success of Operation Accolade, leaving only the island of Kos suitable for a small RAF airfield.

The nearly 200-man LRDG received orders to join the operation in September, 1943. Attached to the Raiding Forces, Middle East, they would join 150 men of the Special Boat Service (SBS), and No. 30 Commando to support the nearly 3,000 regular British troops of 234 Brigade holding the islands. Also on Leros were over 5,000 now-friendly Italian army and navy personnel who manned the coastal defence batteries on the heights, as well as the smaller emplacements guarding the bays and harbours. Five LRDG patrols were directed to coastal battery positions serving as observation points. Others set up watches on outlying islands astride the sea and air routes to the Dodecanese. Their overall task was to report the movement of enemy shipping and aircraft and to stiffen the morale of Britain’s new Italian allies. Some of the islands were occupied by the Germans, so those patrols had to operate covertly.

In early October, Kos fell to the Germans. For the British, it was a serve blow; it and Leros were mutually dependent. Kos had the airfield, while Leros had the naval base, which meant the strength of the combined force was now broken. The loss of Kos along with its two Spitfire squadrons was a major setback. This was the only island from which fighter aircraft could operate, to protect the sea and land forces in the Aegean. It also put the enemy in a greatly enhanced position to gain control of the rest of the islands.

With Rhodes and now Kos in enemy hands, and with little support for Accolade from General Eisenhower, the question presented itself: Why did Churchill not abandon the mission? In retrospect, withdrawal from the Dodecanese at that time would have been the better option, and left for another day as a combined Allied force action.

Germany valued the possession of the Dodecanese so greatly, that planners in Berlin withdrew some of the best forces from Russia, France and Italy to reinforce the islands. Furthermore, they transferred considerable air and naval power from other fronts there. Significantly, for the first time since Crete in 1941, Germany employed a force of nearly 500 parachutists, made up of elite Fallschirmjager and Brandenburg troops, who jumped into Leros from Ju 52 transports or landed on other smaller islands from floatplanes. It would be the last time in the war, that such a large volume of German parachutists were used in an airborne attack. Consequently, with a combination of first-class troops and total dominance of air power over the five-day battle for Leros, victory was attained at considerable loss to the defenders. The Germans later expressed great respect for the LRDG as good fighting men. This was acknowledged on a number of occasions to captured members of the unit.

The LRDG suffered its greatest loss in one action with the assault on the island of Levitha on Oct. 23. This ill-conceived operation lasted nearly two days and cost the group five killed and 36 captured, with only seven escaping the island. Of that, 19 POWs and four killed or missing were New Zealanders. The patrol was ordered to carry out a conventional infantry assault and capture the small enemy-occupied island. It was thought to be defended by a small garrison. Yet despite protest from the LRDG commanders, initial reconnaissance was not permitted to confirm this. Furthermore, the men did not normally operate as ordinary infantryman, as they were specifically trained as specialists, skilled in intelligence gathering and covert operations. Nonetheless, they undertook the mission and landed under the cover of darkness.

At first steady advances were made, taking enemy positions and mounting a good fight, taking many prisoners. Though eventually, they were worn down and had to surrender to an overwhelming force, which attacked from both the ground and the air. It was a big setback for the Group, as nearly a third of its members had become casualties or POWs. A tragic waste of specialist troops, more so when several thousand British servicemen were still based on Leros. A Brigade infantry assault would have been more fitting to the task.

The losses caused an immediate flurry within the New Zealand government, after it was revealed that their troops had been consigned to the Aegean without official approval. The government required that it had to be consulted before its soldiers were committed to a new theatre of war. Further discussions with the British government concluded that the New Zealanders would be permanently withdrawn from the LRDG. It was agreed therefore, that the A (NZ) Squadron LRDG would be pulled out as soon as the tactical situation allowed, though they remained in Leros until its capitulation on Nov. 16. While most of the Brigade troops were captured, many of the LRDG managed to escape the island employing their specialist evasion skills. The New Zealand squadron was finally disbanded in early January 1944.

The battle for Leros lasted nearly five exhausting days. It was an especially violent action with much close-quarter fighting, along with extensive bombing resulting in significant casualties. The LRDG were also one of the few military units in which majors and colonels led patrols into combat and fought alongside their men. They equally shared all the privations and hardships, and some were killed in action including their commander. The respect and bond between LRDG officers and men, was a far cry from what men were accustomed to in the regular army.

On the scale of wartime activity in late1943, the Dodecanese operations were just a sideshow, still not widely known in WW2 military history. Yet for those who served and died there, it was no sideshow. The cost was high on all sides.

Overall, Operation Accolade resulted in the loss of one third of the entire British Mediterranean Fleet in the Aegean, together with a complete infantry brigade (over 3,000 men). The LRDG was also decimated. At great cost, Churchill had lost his gamble. In all, according to German records, some 4,600 British servicemen were taken prisoner on Kos and Leros, another 357 troops had been killed. It it’s three-month deployment to the region, the LRDG lost 12 were killed in action, including its commander and two missing, presumed dead. Another later died in England as a result of serious injuries from a jeep accident on Leros. In addition, about 115 patrolmen were taken prisoner and one later died while a POW. In all, nearly two thirds of the LRDG committed to the Dodecanese operations were lost.

The disastrous outcome was a bitter disappointment for Churchill and came as a shock to public opinion at home. On most fronts at that time, the war was going in the favour of the Allies. It would be Germany’s last successful operation to conquer and occupy foreign soil in the war.

In hindsight, the Aegean gamble could have been avoided. Nonetheless, it was fought bravely by all combatants. This story will provide insight into the LRDG’s contribution to that campaign and the last action the New Zealanders fought with the Group.

Brendan O’Carroll is the author of The Long Range Desert Group in the Aegean published by Pen & Sword Books. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand. Brendan has numerous other published works and articles to his credit. In 2006 his work was recognized by awards from the New Zealand Military Historical Society.

Brendan O’Carroll is the author of The Long Range Desert Group in the Aegean published by Pen & Sword Books. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand. Brendan has numerous other published works and articles to his credit. In 2006 his work was recognized by awards from the New Zealand Military Historical Society.