“The Ferguson was the remarkable creation of a remarkable man. Today it is remembered as a curiosity.”

By John Danielski

IT WAS THE rifle that could have won the American Revolution for the British. A technical marvel more than 50 years ahead of its time, this breech-loader received its baptism of fire at Brandywine Creek outside Philadelphia on Sept. 1, 1777.

Major Patrick Ferguson, the weapon’s inventor, put his experimental rifle to his shoulder and centered the sights on a high-ranking American officer in buff and blue. Considered to be one of the finest marksmen in the British army, Ferguson knew it was an easy shot — the target was just over 100 yards away and he had a clear line of sight. Ferguson had no idea who the enemy officer was since the man’s back was turned, but he was impressed by his enemy’s height and bearing. At the last second, Ferguson lowered his weapon, deciding the business of a proper British officer was honourable combat, not assassinating opposing commanders. George Washington would live.

Born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland in 1744, Ferguson was respected as much for his humanity as his initiative. Growing up in Edinburgh in a family more distinguished for its pedigree than its fortune, he was familiar with many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment and from adolescence displayed a penchant for things mechanical. Lord Cornwallis called him “brilliant” and felt the rifle named after him never received the recognition due it.

Ferguson developed his extraordinary weapon after beginning light infantry training in 1774. A veteran of fighting on the Continent, he had been impressed by the stubby jaeger rifles employed by allied German skirmishing units. Though deadly accurate, they were too slow to load. Unlike conventional smooth-bore muskets carried by ordinary soldiers, muzzle-loading rifles required wooden mallets to pound the ball down into the rifling grooves. Drawing on the designs of French gunsmith Isaac de Chaumette and English inventor John Warsop, Ferguson envisioned a breech-loading weapon that needed no ramrod, could be reloaded at the walk, and had more than twice the range of a common musket. While three shots a minute was good for a Brown Bess, a skilled operator of the Ferguson could do much better.

The secret of Ferguson’s rifle was a moveable breechblock. Unlike earlier breechblocks, his weapon incorporated a screw mechanism into the trigger guard with a handle that could not detach, become lost, or get in the way when not in use. He also developed a unique 12-thread screw for the breech plug. The screw was tapered and slotted: the diagonal threads allowed the breech to be fully opened with one downward counter clockwise turn of the handle. An upward clockwise turn sealed the breech. When the breech was closed, those same threads gave a good gas seal because matching threading was built into the barrel. Adding a mixture of tallow and beeswax to the threads further improved the efficiency of the seal.

When the breech was open, the shooter inclined the weapon slightly forward, and placed a .648-inch ball into the barrel. He then added powder and sealed the breech, letting any excess powder simply fall away. The ball needed no wadding; it was held firmly in place because it was larger slightly larger than the .645-inch barrel. When fired, the ball compressed to fit the eight lands and grooves of the hexagonal barrel: giving one full twist in 60 inches.

Fouling caused by unburned powder was a problem for all black powder weapons, but the Ferguson enjoyed an advantage in this regard as well. When the breechblock was lowered most of the fouling fell away and the rest could be easily wiped off.

The weapon had front and rear sights calibrated for ranges from 100 to 500 yards, though 300 was probably its effective limit.

Though most rifles of the era did not take a bayonet, Ferguson’s accepted a socket bayonet of 30 inches.

Based on an enlisted man’s weapon in the museum at Morristown National Historical Park, the Ferguson weighed 6.9 pounds. It was 49 3/8 inches in length and had a 34 1/8 barrel. Its dimensions approximated those of the Baker Rifle, which won fame in the Napoleonic Wars. And like the Baker, the Ferguson was short enough to be reloaded from a variety of positions.

On Oct. 2, 1776, Ferguson gave a compelling demonstration of his rifle for King George at Woolwich. In a driving rainstorm that would have rendered muzzle loaders unusable, he fired four shots a minute for ten minutes. To conclude the demonstration, he picked up the pace and managed six rounds in a minute.

At one point he allowed the rain to fill the opened breech and was able to clear the water and get the weapon firing again in just a few moments.

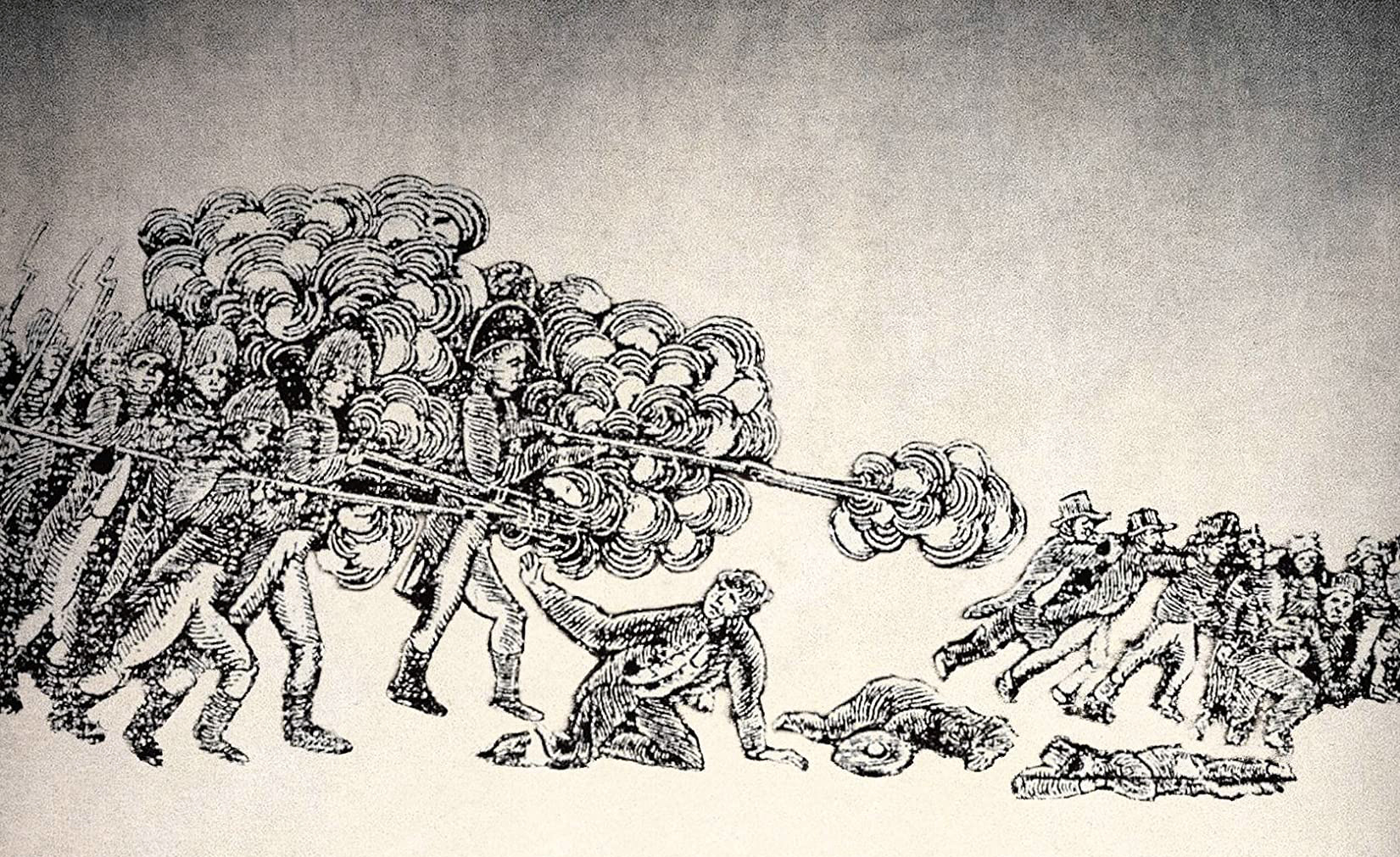

As a reward for the King’s pleasure, Ferguson was allowed to form an experimental rifle corps of 100 men. Its debut was also its final performance. When Ferguson was badly wounded at Brandywine, the corps was broken up. The men found themselves reassigned to regular units and most of their weapons were lost to history.

Ferguson died heroically at the Battle of King’s Mountain in South Carolina in 1780. Though just over 100 Fergusons were manufactured, only five examples are known to exist in the U.S. today: the best preserved one being that of Captain Fredric de Peyster whose descendants donated it to the Smithsonian Institution. Should one in reasonable condition appear on the antique market in the near future, it would likely fetch seven-figures.

Two factors kept the Ferguson from becoming a revolutionary weapon in a revolutionary war: expense and conservatism.

The weapon was costly to manufacture and the British government was very concerned with frugality. The Ferguson stretched the limits of the technology then available and required a gunsmith with far more than average skill. A Brown Bess might be a crude weapon but armouries could produce 20 for the cost of one Ferguson.

The Board of Ordnance chiefs of the time were skeptical of innovation, preferring to stick with tried and tested weaponry. Adoption of the Ferguson in large numbers would have required a wholesale and exhaustive reevaluation of the tactics and maneuvers of the day: an exceedingly difficult thing to do in wartime. It should be remembered that the repeating Colt revolver was initially rejected by the U.S. Army for much the same reasons that the Ferguson never won general acceptance.

The Ferguson was the remarkable creation of a remarkable man. Today it is remembered as a curiosity: a what-might-have- been that gives National Parks rangers a story that tourists at King’s Mountain find endlessly compelling. Though a footnote to history rather than a game-changer, we should not fail to see it for what it was: a great leap forward in the development of firearms.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: John Danielski is the author of the Tom Pennywhistle series of novels about a Royal Marine officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Book five of the series, Bellerophon’s Champion: Pennywhistle at Trafalgar was published by Penmore Press in May. For more, visit: www.tompennywhistle.com or check him out on Amazon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: John Danielski is the author of the Tom Pennywhistle series of novels about a Royal Marine officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Book five of the series, Bellerophon’s Champion: Pennywhistle at Trafalgar was published by Penmore Press in May. For more, visit: www.tompennywhistle.com or check him out on Amazon.

(Originally published on Aug. 24, 2019)

As I recall, the British lost the Battle of Isandlwana partially because they were too cheap to provide the better, newer cartridges for their rifles.

YES – IN NUMBERS IN A LINE BATTLE IT COULD HAVE MADE A DIFFERENCE, I GO INTO DETAIL ON IT IN MY STORY “THE FERGUSON RIFLE” AT GREATWAR,COM..

RICK KELLER/ GWM. WE BUILT 15 AND PUT THE GUN THROUGH ITS PACES.E