“I absorbed a lot of the stories about the battle, which was the decisive military engagement in Ireland between the forces of King James ll, the Jacobites, and his usurper as king of England, Scotland and Ireland, William of Orange, the Williamites.”

By Joe Joyce

THE BATTLE OF Aughrim is remembered as the bloodiest clash of arms ever to take place on Irish soil. As many as 6,000 were killed during the engagement, which was fought on a sunny Sunday afternoon in July of 1691.

My work as a fiction writer has given me a better understanding of what happened there and a deeper appreciation of the people involved. It’s also left me questioning whether a man who has gone down in Irish history as a traitor really was one.

I grew up with the battle of Aughrim; it was where I lived as a child. My schoolteacher father had a deep interest in the local history, which I didn’t share. Nevertheless, I absorbed a lot of the stories about the battle, which was the decisive military engagement in Ireland between the forces of King James ll, the Catholic Jacobites, and his usurper as King of England, Scotland and Ireland, William of Orange, the Protestant Williamites.

The Battle of the Boyne, which took place a year earlier, is better known and remembered, especially among Protestants in Northern Ireland. Yet it was less decisive in military terms than Aughrim, although more important strategically and politically.

After being defeated at the Boyne, the French-backed Jacobite army withdrew intact to the west of Ireland, behind the line of the River Shannon. It saw off Williamite sieges of the river’s two main towns, Athlone and Limerick, and was undefeated going into 1691, although it had lost control of most of the island.

My book, 1691: A Novel, is the story of that fateful year whose consequences for Ireland have continued down to the present day. It begins in May as campaigning gets underway once the grass is plentiful enough to feed both armies’ horses.

A French general, the Marquis de Saint-Ruhe, arrives at Limerick to take command of the Jacobite army. The Williamite forces under Dutch general Godard de Ginckel leaves Dublin with the task of bringing the campaign in Ireland to an end.

Ginckel successfully seizes Athlone and crosses the River Shannon. Against the advice of his generals, Saint-Ruhe decides to make a stand some 20 miles to the west at the tiny village of Aughrim. He positions his 20,000 army on a hillside overlooking a marsh.

Ginckel has little choice but to join battle with his similar-sized force. He does so on July 12 (by the Julian calendar). His infantry is repulsed time after time as they struggle through the marsh to take the hill. Ginckel’s cavalry makes no progress against the Jacobite cavalry on the southern flank of the front, the only dry land on which they can both engage.

Eventually, in a last desperate ploy, the Williamite cavalry attacks along a narrow causeway at the northern end of the front. The Jacobite lines have been weakened here by the diversion of defenders to other areas where most of the fighting has taken place.

The Williamite cavalry breaks through. Saint-Ruhe leads a counterattack but is decapitated by a cannon shot. His cavalry unit picks up his body and rides away. Those at the rear of the Jacobite lines see this and begin to melt away too. Soon, it turns into a catastrophic rout for the Jacobites.

Galway surrenders shortly afterwards on good terms. The remnant of the army falls back on Limerick, which is then besieged by the Williamites. Help is expected from France but doesn’t materialize in time. A treaty is negotiated and the bulk of the Jacobite army is allowed go to France.

The book began as a sort of atonement to my father for my lack of childhood interest in his passion. Loosely inspired by Michael Shara’s classic account of Gettysburg, The Killer Angels, I concentrated on two opposing generals, the Irish Jacobite Patrick Sarsfield and the Scottish Williamite Hugh Mackay.

My account stays close to the history. The fiction lies in the dialogue and thoughts of the people involved, teasing out their personalities, friendships, and enmities. In a story that is frequently portrayed as Irish versus English, it was surprising to find how many of the commanders on both sides were neither and knew each other. A significant number had served together previously in one army or another, whether English, Dutch or French.

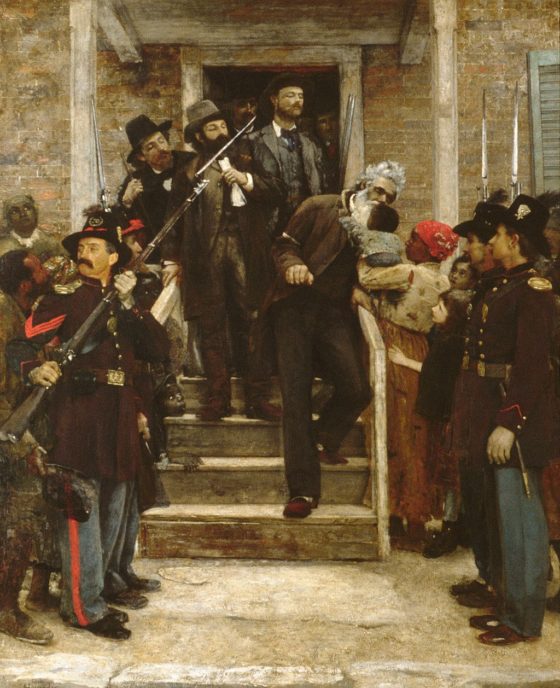

But the main surprise for me related to Henry Luttrell who has gone down in Irish history as a traitor. He was a colonel in the Jacobite cavalry and a close friend and adviser to Patrick Sarsfield. At Aughrim he was said to have deliberately let the attacking Williamite cavalry through. He subsequently switched sides and received a large pension from the English government.

Trying to imagine myself back in the time and place, however, a different and a more fascinating, story emerged.

Luttrell was not treated as a traitor by his comrades in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Like his friend Sarsfield, he was at odds with Richard Talbot, King James’s representative, and the most powerful man in Catholic Ireland. Unlike Sarsfield, he delighted in political intrigue.

During the siege of Limerick, the French Jacobite commander was alerted by a French Williamite commander that a secret message was being sent to Luttrell from the Williamite general Ginckel. The message was intercepted. Its content was anodyne but Luttrell was arrested and court martialled. Although the court was made up of Luttrell’s political enemies, it acquitted him of treachery. But Talbot and Luttrell’s erstwhile friend, Sarsfield, refused to release him.

He was finally released after the treaty was signed and did a deal with the Williamites to take his cavalry unit over to their army. And to receive an annual pension if this arrangement was not implemented. It wasn’t and he received the pension.

From the Williamite point of view, it was a perfectly executed psychological operation long before psy-ops became a recognized phrase, sowing dissension among the enemy and depriving its crucial decision maker of his friend and closest adviser during the critical treaty negotiations.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Joe Joyce is the author of five previous novels. His Echoland series involves the hunt for Nazi spies in neutral Dublin during the Second World War and the country’s intelligence service’s role in resisting Allied pressure on Ireland to join in. 1691: A Novel is available from Amazon as a paperback and on Kindle. www.joejoyce.ie

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Joe Joyce is the author of five previous novels. His Echoland series involves the hunt for Nazi spies in neutral Dublin during the Second World War and the country’s intelligence service’s role in resisting Allied pressure on Ireland to join in. 1691: A Novel is available from Amazon as a paperback and on Kindle. www.joejoyce.ie

1 thought on “A Novel Approach to History – Fiction Writer Takes a Fresh Look at Ireland’s Deadliest Battle”