“Lugosi seldom spoke of how the Great War and its immediate aftermath influenced the roles he chose or how he performed them.”

By William Poole

THE 1915 Carpathian Campaign was a disaster for Austria-Hungary. Casualties reached as high as 50 per cent in what would be also be remembered as the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive.

Among those who suffered during this butchery was Lieutenant Blaskó Belá Ferenc Dezo, later known to the world as Bela Lugosi (1882 to 1956).

Lugosi will be forever identified with Universal Pictures’ 1931 classic Dracula. In fact, there’s been virtually no on-screen adaption of the famous novel since that doesn’t somehow pay homage to his portrayal of the Transylvanian vampire. Even today, few Halloween costumes, animations, or cereal boxes can avoid the permanent mark he left on the character.

Remarkably, Dracula is far from Lugosi’s best acting. In the ‘30s his performance in films like White Zombie and The Raven made otherwise workmanlike productions into surreal nightmares.

But Lugosi channeled all of his dark energy into the 1934 film The Black Cat. A serious cinematic achievement in its own right, the film was one of German émigré director Edgar G. Ulmer’s finest works. Ulmer had been heavily influenced by Weimar cinema, especially the work of F.W. Murnau of Nosferatu fame and Fritz Lang, famous for his 1927 dystopian sci-fi Metropolis.

The Black Cat, which also stars Boris Karloff, comes very close to becoming an allegory of the First World War. It was a theme that haunted almost all horror films in the ‘20s and ‘30s.

The story focuses on the bad blood between two veterans of the conflict. Although the war has been over for 15 years, Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi) harbours a grudge against Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff) for leaving him to die during a battle against the Russians. When the two find themselves together again in a foreboding Caligari-esque mansion built on an old Eastern Front battlefield, dark psychological drama ensues.

Lugosi seldom spoke of how the Great War and its immediate aftermath influenced the roles he chose or how her performed them. The actor, normally known for his quiet reserve, shocked the cast and crew on the set of The Black Cat when he began inexplicably divulging troubling details about his time at the front.

During one such confessional, he told his fellow-actors and the wife of the director that he had been a “hangman” for the Austro-Hungarian army and that the experience of killing left him “thrilled” and “guilty” all at once.

Amazingly, little attention has been paid to Lugosi’s war experience, even in major biographies about him. One such account of his life runs to almost 500 pages – plus notes – yet gives it little more than one paragraph. What little we do know about Lugosi’s experiences from 1914 to 1919 perhaps helps explain what sounds like fragmented ramblings on the set of The Black Cat.

A figure of growing importance in the National Theatre of Budapest in 1914, Lugosi volunteered in the 43rd Royal Hungarian Infantry where he eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant. Mobilized at the war’s outset, the regiment saw fighting with the Russians in the fall of 1914 and, most disastrously, the winter of 1915.

The Carpathian Campaign was a difficult one for the Central Powers. German troops had destroyed an entire Russian army in 1914 at the Battle of Tannenberg but, in what would later become southern Poland and western Ukraine, a new Russian offensive pushed into the borders of Austria-Hungary itself. The Dual Monarchy made a series of counterattacks that rocked Russian troops back on their heels. It was during one of these engagements, at Rohatin (or Rohatyn) in what is now western Ukraine, that Lugosi suffered his first wound.

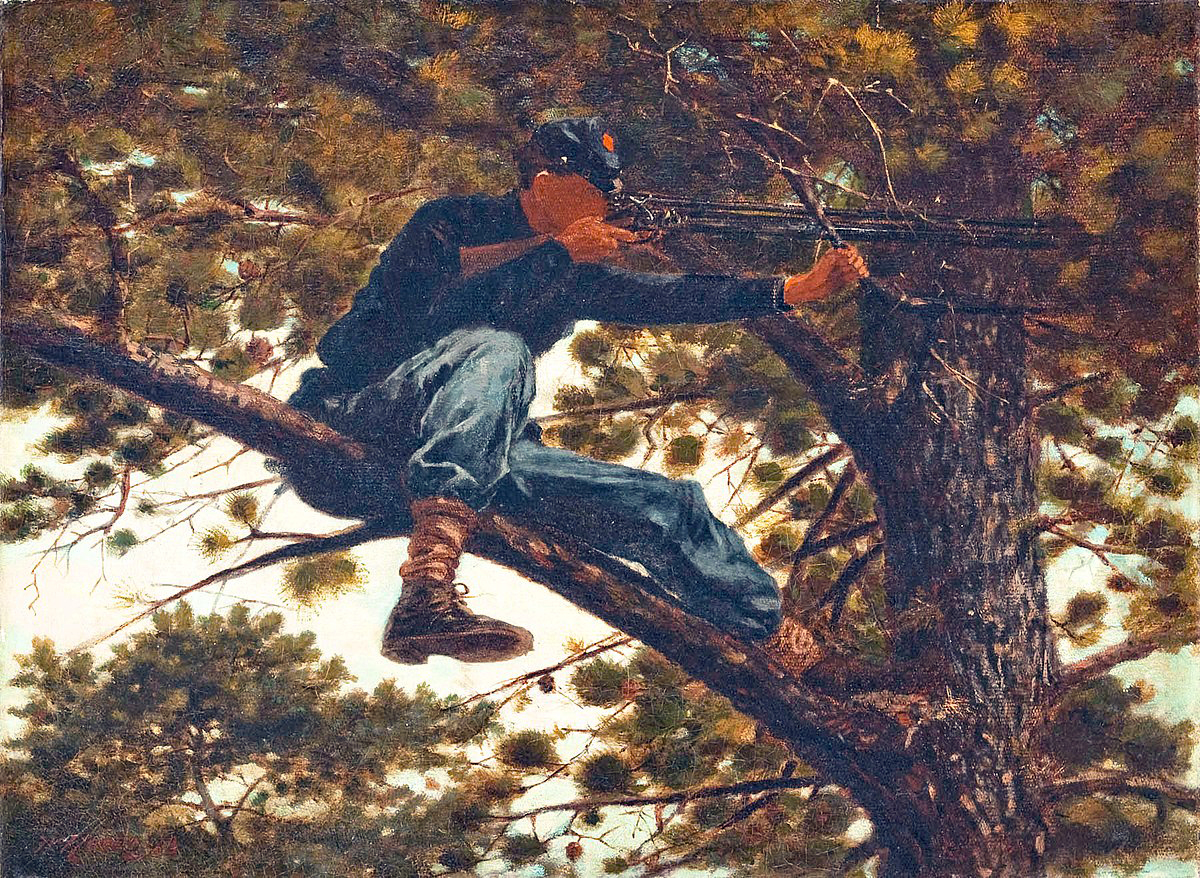

He recovered only to take part in a new offensive that sough to drive the Russians completely out of the southern passes of the Carpathians. It was a costly failure. Lugosi, who fought as a member of an elite ski corps, received a second “wound medal” for injuries sustained in the fighting.

During the battle, the future king of the vampires would later recall to a love interest, he found himself trapped “beneath a mound of corpses.” Strangely, being buried alive was a not uncommon experience for soldiers of the Great War. Exploding shells often caused trenches to collapse or dugouts to cave in leaving victims entombed alive.

In May of 1915, Lugosi was reportedly a participant in yet another attempt to drive the Russians back. The Tsar’s forces had enjoyed nine months of relative success against the Central Powers up to then, but it ended in a series of bloody battles that included what John Keegan describes as “the largest barrage yet attempted on the Eastern Front.” During the massive bombardment, German guns lobbed nearly three-quarters-of-a-million shells onto Russian positions.

The following year, Lugosi was discharged from the service; “mental collapse” has been cited as the reason. Of course, millions of Great War soldiers suffered from what in Germany and Austria was often called Kriegneuroses or “war neurosis,” and what British army doctors referred to as shell shock and the French diagnosed as commotion.

After his discharge, Lugosi returned to acting and began landing film roles in Hungarian cinema. He would later become swept up in the political upheaval that rocked Central Europe in the months following the 1918 Armistice.

Lugosi’s own son, Bela Lugosi Jr., briefly summarized this turbulent period in a 2006 bio of his father: “Dad took an active role on behalf of the actor’s union, found himself on the wrong side of the ruling party, and was forced to flee the country.”

Indeed, he had taken an active role in the movement. In his book, The Immortal Count, biographer Arthur Lennig, reports that at the beginning of the Hungarian Revolution in 1918, Lugosi proudly displayed to a fellow actor his union membership card from his days working as a laborer and later an apprentice locksmith. He soon helped to found a radical actors guild that called for the nationalization of theatre in Hungary and an end to its “ranking system” by which actors received parts according to seniority. Some of his fellow actors, Lenning writes, worked for Lugosi’s expulsion.

The year 1919 brought the creation of Belá Kun’s short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic. A Romanian invasion promptly brought an end to the socialist experiment. The collapse of the regime led to a wave of reprisals from the right-wing government of Miklos Horthy. A former admiral under the Hapsburgs and the hero of the major naval victory at the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, Horthy would later cooperate, albeit reluctantly, with Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

After being driven from his homeland, Lugosi went to Vienna and then on to Germany. Still pursued by the new Hungarian regime, he worked his way to New Orleans aboard a merchant ship and then voyaged to Ellis Island where he became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1931.

I think the heirs of Lugosi’s reluctance to talk about the actor’s early life is understandable. Bela Jr’s reticence on such subjects has been part of his honorable effort to defend his father’s reputation. Much, too much, has been made of his collaboration with Ed Wood in the regrettable Plan 9 From Outer Space. Lugosi died in 1956 amid production of the sci-fi cult-classic. Many today know of his alcoholism and drug use during this period; few that he successfully sought treatment for both. Even fewer have wondered if his struggle with substance abuse had anything to do with the astonishing violence he had witnessed and engaged in from 1914 to 1916.

Much is lost by not delving further into the great actor’s past. Along with an astonishing career in film, Lugosi was a wounded veteran and a revolutionary who suffered exile for his high ideals. Indeed, in Budapest, he deserves greater public recognition than he receives: a single bust in an out-of-the-way alcove in Vajdahunyad Castle, literally snuck into the ancient fortress by an admiring artist in 2003.

W. Scott Poole is the author of Wasteland: The Great War and the Origins of Modern Horror. He is a professor of history at the College of Charleston who teaches and writes about horror and popular culture. His past books include the award-winning Monsters in Americaand the biography Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror. He is a Bram Stoker Award nominee for his critically acclaimed biography of H. P. Lovecraft, In the Mountains of Madness. Follow him on Twitter @monstersamerica

NOTE: The author would like to acknowledge the contributions made by the research of C.J. Wilkinson and Andrew Pourciaux to this essay.

1 thought on “Dracula Goes to War – Bela Lugosi, WW1 and the Making of a Macabre Hollywood Legend”