“Hollywood couldn’t write a better ending to Gene’s wartime experiences.”

By Marcus A. Nannini

GENE METCALFE, a paratrooper with the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, was aboard one of dozens of C-47s to appear over the grassy meadows near Groesbeek, Holland at 13:30 hours on Sept. 17, 1944. The last man to jump from his transport plane, after hitting the silk, the 22-year-old private from DeKalb, Illinois looked up at the aircraft he’d just exited and noticed the left wing had been severely damaged. Despite being hit by ground fire, the Skytrain’s pilot managed to keep the bird steady long enough to allow the all the paratroopers to bail-out. Gene watched as the plane rolled-over and disappeared behind a line of tall trees.

Ten hours later Metcalfe found himself with his platoon-mates in Nijmegen, perched behind a large tree lobbing grenades at a troop carrier of the elite German 10th SS Panzer Division. During the firefight, Gene was knocked cold by an enemy artillery round. His best friend risked his own life darting across a road to help the unconscious paratrooper. The man found the helmet-less Gene lying face-down in the dirt. After rolling Metcalfe over and seeing blood pouring from his comrade’s right ear he assumed the worst and withdrew to safety. Amazingly, Gene wasn’t dead.

The abandoned and unconscious paratrooper was soon discovered by the Germans, who interrogated him and promptly shipped him off into captivity.

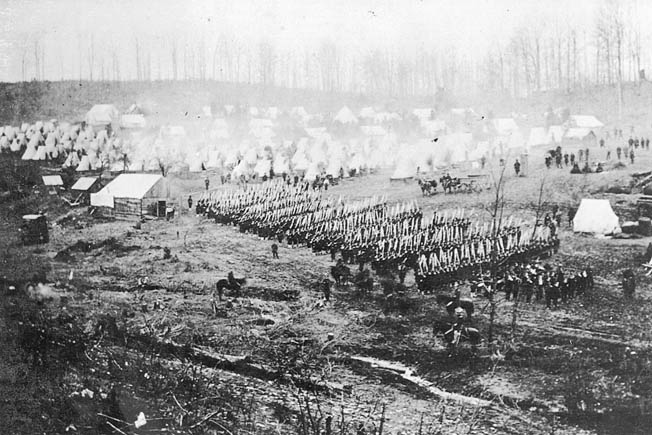

Four days later, Gene reached Stalag XII-A, a sprawling prisoner-of-war encampment outside Limburg, Germany. Just as he and his fellow prisoners were entering the compound, air-raid sirens suddenly began wailing. Moments later, Allied planes appeared overhead sending the thousands of prisoners held there scrambling to their respective barracks, most of which were little more than large, circus-style tents. The prisoners had little to fear from bombs; the camp wasn’t a target. The danger was being shot by the guards. Among the Stalag’s many standing orders was one that forbade prisoners from being outside during an air raid — violators faced immediate death. The Germans hoped to prevent the inmates from taking in the sight of hundreds of Allied bombers flying unmolested over the Third Reich, a spectacle that would raise the morale of the POWs.

Gene watched as one 82nd Airborne paratrooper defied the rule and remained in the compound. A guard in a tower bellowed at the man get inside, but the prisoner only laughed, pointed up at the bombers, then pointed to the guard and laughed some more. After watching the sentry train his MG-42 on him, the unruly POW quickly made for the tent’s entrance. He was too late. A burst from the machine gun tore into the prisoner. Three bullets struck the man in the back and a fourth lodged in one of his legs. The stricken prisoner fell forward, right on top of Gene Metcalfe who’d been watching spellbound from just inside. In fact, one of the rounds whizzed past Gene’s left ear. Another inch closer and he’d have been killed.

With the air-raid sirens still blaring, Metcalfe had to act fast. He picked up the wounded paratrooper and threw him over his shoulder as blood poured out, spilling across the front of his jacket and trousers.

Metcalfe looked around and asked his fellow prisoners if anyone would help him. No one volunteered. Alone, he managed to carry the bleeding man more than 150 feet to the hospital tent.

As Gene approached the infirmary, three guards converged on him, their rifles at the ready. They ordered him to halt. As he hesitated, Metcalfe glanced up at the guard tower where the trigger-happy machine gunner was still on his weapon.

He noted that each of the sentries before him bore the badge of the “Winter War,” Germany’s disastrous campaign in Russia. Gene imaged all three had likely carried their own wounded comrades to safety at some point and might empathize with him now.

Metcalfe pointed at the red cross on the tent and, using his free hand, indicated he was going there. He took a small, hesitant step forward. No one fired. Encouraged, he took a second step and then a third. As he moved he watched as the guards keep pace with him, never lowering their rifles, yet not firing either.

In what felt like forever, Gene eventually made it to the hospital tent where a British doctor who’d witnessed the entire incident was waiting. The surgeon took the wounded man from Gene who proceeded to wait for the air-raid sirens to stop. Once all was quiet, he returned to his tent.

Gene would wear the blood-stains of the critically wounded paratrooper on his uniform throughout the remainder of his time in the camp, never knowing if the man he risked his life to save even survived the ordeal.

Sixty years later, Gene Metcalfe, well into his 80s, received a mysterious phone call. Amazingly, it was from an Elmer Melchi, the paratrooper Gene saved at Stalag XII-A more than a half century earlier. Gene had always assumed the man he carried must have died from his wounds. The two would soon meet face to face. Their reunion was captured by major U.S. news networks and broadcast across the country in 2005.

Despite the fanfare, Gene received no decorations for either the wounds he sustained during the firefight at Nijmegen nor for his heroism on his first day in the German POW camp.

Those two oversights were finally addressed in a ceremony conducted last month at, at American Legion Post 58 when on Aug. 16, Gene was properly honoured for his World War Two service. His best friend, Ray Mead, the man who had left Gene for dead at Nijmegen, was also present, himself the beneficiary of overlooked honours. And the story doesn’t end there.

This coming Saturday, Sept. 21, exactly 75 years to-the-day of his heroism at Stalag XII-A, Gene Metcalfe will be in Holland as a guest-of-honour. On that day he will be awarded the Netherlands’ highest military award, the Orange Lanyard. Witnessing the event will be his wife, Paulette, his daughter and his grand-daughter. The list of dignitaries also present will include among others Princess Beatrix, former queen of the Netherlands; Britain’s Prince Charles; Peter Hoekstra, U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands; and various NATO military officers and local officials.

Hollywood couldn’t write a better ending to Gene’s wartime experiences. And at 96 years old, he recently returned to softball, a sport he played most of his life. He and his wife are still very active; she gets a “kick” out of it whenever someone in a store or on the street recognizes him and says, “Hey, you’re the guy who was left for dead!”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Marcus A. Nannini is the author of Left for Dead at Nijmegen, which tells the story of Gene Metcalfe’s experiences as a paratrooper and prisoner of war in WW2. It’s published by Casemate. Watch for Marcus’ upcoming Midnight Flight to Nuremberg. For more information, visit: www.chameleonsthebook.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Marcus A. Nannini is the author of Left for Dead at Nijmegen, which tells the story of Gene Metcalfe’s experiences as a paratrooper and prisoner of war in WW2. It’s published by Casemate. Watch for Marcus’ upcoming Midnight Flight to Nuremberg. For more information, visit: www.chameleonsthebook.com