“The ensuing campaign would cost hundreds of lives, raise to the throne a future dictator and set the stage for the first real show down of the Cold War.”

DURING THE LATE summer of 1941, an obscure sideshow of the Second World War would play out in the Persian Gulf.

The Allies, desperate to halt the Nazi advance in Russia, sought to open a supply route into the U.S.S.R. through the Middle Eastern kingdom of Iran, a country that at the time was drifting into Germany’s orbit.

It soon became clear to planners in both Moscow and London that force would be required to open up this all important Persian Corridor. The ensuing campaign would cost hundreds of lives, raise to the throne a future dictator and set the stage for the first real show down of the Cold War.

Prelude to Invasion

In June of 1941, Hitler tore up the two-year-old Molotov Ribbentrop non-aggression pact with Stalin and sent his Panzers surging eastward into the Soviet Union. Up until that point in the war, Russia was more than happy to stay out of the widening conflict. Moscow watched from the sidelines as the Nazis grabbed Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, Greece, Yugoslavia and even large swaths of North Africa. Now with his own country bearing the brunt of the Blitzkrieg, the Soviet despot suddenly found a new ally in Great Britain. British prime minister Winston Churchill, believing that the enemy of his enemy was his friend, immediately looked for ways to help the Soviets stem the tide of Hitler’s armies as they relentlessly drove on towards the Russian capital. For its part, London committed what materiel that could be spared to aid the Soviet war effort. But one issue remained: how to get the weapons, supplies and ammunition into the hands of the Red Army quickly?

A Persian Corridor?

With shipping lanes to Northern Russia threatened by German U-boats and bombers, the Black Sea all but closed to sea traffic from the Mediterranean, and Pacific ports like Vladivostok half a world away, the Persian Gulf seemed the only viable conduit through which weapons and supplies could flow to Stalin unobstructed. There was one catch: the Iranian leader, Reza Shah Pahlavi, wasn’t about to allow the Allied supply convoys safe passage through his kingdom.

Throughout late July and early August, British and Soviet diplomats coaxed, urged and even threatened the Iranians to open up their sea ports and rail lines to the Allied cause. Tehran still refused. With support for Germany on the rise in Iran and pro-Nazi rallies being staged in the streets of the capital, the British and Soviets cast aside any diplomatic niceties and opted for a joint invasion. The Allies would seize Iran and hold it for the duration of the war.

Invasion

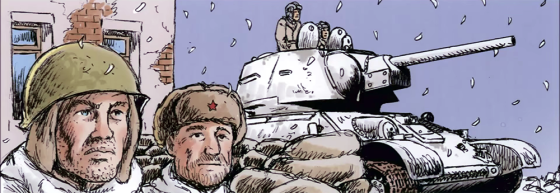

Allied armies converged on the Islamic state from two sides – the British from the Persian Gulf and neighbouring Iraq; the Soviets from the Caucuses.

The invasion opened in the pre-dawn hours of Aug. 25 when the British sloop HMS Shoreham steamed into the port of Abadan, Iran at the mouth of the Shatt al Arab River, surprising and sinking at least two Iranian warships and damaging others. The move coincided with an amphibious assault launched from Basra, Iraq on the opposite bank of the river by units of the Indian Army’s 8th Division under cover of RAF fighters and bombers. With the port in Allied hands, the 8th and units of the 10th Indian Division, along with supporting British armour pressed inland. These forces were soon joined by more British and Indian troops entering Iran east of their bases in Baghdad.

To the North, three Red Army formations swarmed over the border into Iran from the Caucuses. After bombing Iranian defences along the Caspian Sea, the Soviets pushed the 44th, 47th and 53rd armies southward, crushing whatever resistance was encountered. For several days, Iran’s outclassed army and air force tried to stem the onslaught. Tehran even appealed to Washington for help. None was forthcoming.

Within a week, the Iranian army had been all but brushed aside. By September, the British and Soviet units had linked up at Hamadan and had effectively secured a route from the Persian Gulf right into the U.S.S.R. More than 800 defenders lay dead, two Iranian warships had been sunk, several more crippled and six planes had been brought down. Two hundred civilians also died in the fighting. The British casualties were 22 killed. The Soviets lost 40 men.

Aftermath

With Iran under Allied control, London and Moscow replaced Shah Pahlavi with his son, Mohammad. With the father exiled in South Africa, the younger and more conciliatory Shah agreed to work with the Allies. The so-called Persian Corridor was soon open and goods from the British Empire and even the supposedly neutral United States could now make its way into Soviet hands. By way of a bonus, all German and Axis diplomats were expelled from the country and Iran’s vast oil fields could now supply the war effort.

By the end of 1941, America entered the war. Soon even more U.S. made goods, equipment and armaments would be flowing through the vital lifeline and into the hands of the Red Army, all under terms of President Roosevelt’s Lend Lease Program. American military personnel also streamed into Iran to help secure and maintain the link. In January, 1942, the Allies formally signed a treaty with Iran specifying that the occupation would end within six months of the conclusion of the war. For the next three years, more than $11 billion worth of goods (the equivalent of $180 billion in today’s currency) would flow into the Soviet Union, much of it via the Persian Corridor.

The Post War Crisis

For Iran, the occupation didn’t end with the defeat of Nazi Germany. Despite assurances from Washington, London and Moscow that all Allied occupiers would vacate Iran within six months of the end of the war, the Soviets refused to relinquish control of northern Iran.

By the fall of 1945, Moscow had even established two breakaway puppet republics in their zone of the country: a Kurdish state of Mahabad and the People’s Republic of Azerbaijan (which was separate from the Soviet Azerbaijan). The Soviets provided weapons, training and military advisors to the two new states and maintained troops in the region. To the world, it looked like Stalin was planning to stay.

The international community condemned the Russian presence. In fact, the three of the first five United Nations Security Council resolutions in history (numbers 2, 3 and 5) called for a Soviet withdrawal from Iran. Bowing to mounting pressure from the United States, Great Britain, Stalin finally agreed to pull out his troops by March of 1946, but not before inking a deal with the Shah that would allow the Soviets a stake in Iranian oil.

With the Soviets gone, the Iranian army, equipped with surplus British weaponry launched a war to reclaim the breakaway republics. By the summer, it had crushed the fledgling states and with diplomatic support from the United States and Britain, reneged on its oil agreements with Moscow. For the next 33 years, Iran would be one of Washington’s most stalwart allies in the Persian Gulf. In 1979, Islamic revolutionaries would topple the Shah.

(Originally published on MilitaryHistoryNow.com on Jan 24, 2013)

Was the Shah in 79 the son of the one deposed in 41? Great post!

The son who rose to power in 41 was in fact the same deposed Shah from 79. Yes.

And thanks!

Thought so. One of the things I remember about the Shah is that he held this huge parade celebrating Iran’s (Persian) Achaemenid past. It was quite the show and they spared no expense with the soldiers, chariots, cavalry of the period costumes. But, apparently, he was not Islamist enough for some.

I think I saw footage of that myself in some documentary from years back about the fall of the Shah. There were Legions of soldiers dressed in ancient uniforms. Judging by the look of the footage it was shot in the 1970s.

Yep. It was an anniversary of some sort, 2,500 years maybe celebrating Darius the Great. Not sure, but yes it was in the 70’s. I was into ancient wargaming at the time and the guy who had the Persians was thrilled to get the uniform pictures for his Achaemenid wargames army.

When the second Shah, Reza Pahlavi II, rose to power in 1941 after his father, Reza Pahlavi I, was deposed following his refusal to work with the Allies, the United States supported his increasingly tenuous hold on power, despite increasing calls from the people for free and fair elections, and CIA assets in Tehran’s increasingly urgent warnings over the curse of twenty years. But our oil and intelligence interests for spying on the Soviets in the region outranked any thought of supporting some fledgling democracy again and again and again.

We were only staying in Iran for six months after the war. That’s what we told them.

After ignoring ten years of warning from the CIA and our own embassy, and then their missive in late 1978 from Tehran that our puppet leadership through the Shah wasn’t working and further that Iran was going to fall if we didn’t change our policy and start talks with the country’s leading clerics immediately. But no, came the answer.

So instead, in 1979 we got overthrow and hostages and an assured theocracy for the next three generations. The Shah’s family fled the country.

His oldest son, Reza Pahlavi III, was already in the United States going to college. He was a classmate of mine. He was a quiet, serious young man with the same look and life of the rest of my college classmates in 1980’s Boston. We all danced to Michael Jackson, read until our eyeballs burned, and cheered and screamed and cried during The Miracle on Ice.

At the time, I remember being both impressed and proud at the time of my fellow classmates, and more widely, my fellow countrymen who were uniformly tolerant and often sympathetic to him and his refugee situation. Our pride in America having been stirred by the Olympics, we were even more aware of what life would be life without it. To be a man without a country was something we could understand. The World War II generation understood this on a personal level.

Sadly, I feel nowadays that he would not even be welcome to stay in the United States on his student visa and if he were to stay, would be subjected to all kinds of racial and religious epithets.

These are sad times.

Excellent and illuminating article – thanks.

Thanks for the kind word.

Great story but you inked over the critical part of the Molotov agreement – the USSR divded Poland with Nazi Germany.

Wow, this we never hear of. Great article.

the same behavior from centuries of colonialists and evil states

Excellent timing , and illuminating facts.. Thank you.

Hitler “tore up the pact” with Stalin because Stalin’s three million troops were about to rush through Germany to take over the rest of Europe.Dunderheads decided to help Stalin achieve his aim. See Suvorov’s ‘Icebreaker’.

Don’t think so Rolf. 3 million poorly armed peasants vs German panzer divisions. Think we know how that would have went.