“In the last 100 years, there have in fact been at least three successful mass cavalry charges.”

By Rafe McGregor

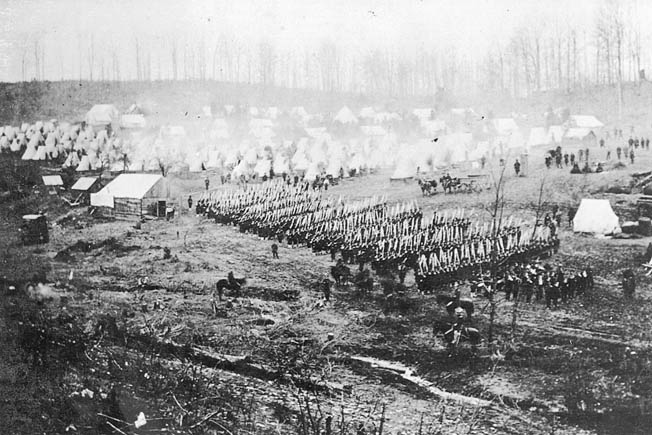

ISAAC NEWTON WASN’T thinking about cavalry charges when he penned his Second Law of Motion in 1687. Yet the famous equation, “force equals mass multiplied by acceleration,” effectively captures the deadly effectiveness horses and riders on the battlefield. It was certainly a calculation known to generals and soldiers alike as far back as the Bronze Age. In fact, cavalry dominated warfare from the ancient world right up until the mid-19th century. The advent of accurate repeating rifles and the Gatling gun heralded the end of the era of dragoons and lancers.

Despite this, the date of history’s “last cavalry charge” is the subject of much debate. The British at Omdurman in 1898 is a popular choice. The Spanish Nationalists at the 1938 Battle of Alfambra is less popular, but more recent. And the American-led Filipino charge at Bataan in 1942 is better-known, but was much smaller in size. In the last 100 years, there have in fact been at least three other successful mass charges. Let’s look at them.

The Affair of Huj

The Middle Eastern theatre of the First World War never reached the kind of stalemate produced by trench warfare on the Western Front. In fact, the fighting in the desert remained mobile throughout the duration of the conflict. As such, there was much greater scope for regular and irregular soldiers mounted on horses and camels. The aim of the Allied Southern Palestine Offensive was to break the Ottoman lines and capture Jerusalem; the Battle of Beersheba on Oct. 31, 1917, a British victory, was a highlight of the campaign. The Ottoman Eighth Army retreated towards Jaffa, their withdrawal covered by German and Austro-Hungarian artillery and machine gun detachments. On the morning of Nov. 8, a rear-guard of approximately 2,000 Turks was pushed back towards Huj, a village 10 miles north-east of Gaza, by a combined British Empire force of cavalry, infantry, and machine guns that included the 5th Mounted Brigade. The outfit was composed of the Warwickshire, Worcestershire, and Gloucestershire Yeomanry regiments. In fact, the Warwicks and the Worcesters were in the lead when the Turks decided to make a stand on a ridge one mile south of Huj.

Two hundred Turkish infantry had deployed with an Austro-Hungarian 75 mm battery and a German machine gun detachment to the west. To the east, another 200 Turkish infantry formed a line with a Turkish battery of mountain guns. They were supported by a battery of German howitzers. As the Commonwealth forces closed on the enemy, the Yeomanry dismounted and took cover at about 1,000 yards from the enemy. The commanding officer of the Worcesters decided that he needed reinforcements before attacking and left the Warwicks’ commanding officer, Lt. Col. Hugh Gray-Cheape, temporarily in charge. Gray-Cheape was then ordered to assault immediately with 75 Warwicks, 85 Worcesters and a machine gun detachment.

As soon as the Yeomanry rounded the ridge they had been using for cover, they were met by a hail of artillery, machine gun, and rifle fire. Gray-Cheape’s men charged straight at the Turkish infantry to the east and although losses from the howitzers were heavy, Turkish marksmanship was poor. The German gunners began to retreat as soon as it became clear that the line was in danger. Gray-Cheape and his Warwicks quickly outflanked the Turkish guns and caught the Germans on the run; Major Edgar Wiggin, temporarily in command of the Worcesters, broke off from Gray-Cheape and turned towards the Ottoman lines to the west, 300 yards away. The smaller Yeomanry column, under Captain Rudolf Valintine of the Warwicks, had taken heavy casualties en route to the Ottoman right. To make matters worse, they had to charge the final 150 yards up a steep hill. Spotting Wiggin’s men closing in from the east, the Turks feared that they were being outflanked by a much larger force and fled. The Austro-Hungarians were made of sterner stuff. They levelled their artillery and blasted what was left of Valintine’s force at a range of only 25 yards. The gunners were soon mopping up Wiggin’s men with small arms. A melee of sabres and bayonets ensued. The remaining mounted men, survivors from both Valintine and Wiggin, made a third and final charge at the retreating German machine gun detachment, which they overran. In 15 minutes, the Turkish infantry was routed, with 70 taken prisoner and 11 guns and four machine guns captured. Estimates of British losses vary, but it seems that about 30 of the Yeomanry were killed and about 55 wounded, with nearly two-thirds of the total number of horses involved killed.

Charge of the Savoia Cavalleria

The Italian Army began the Second World War with 14 cavalry regiments divided into three divisions. One of these, 3a Divizione Celere ‘Principe Amedeo Duca d’Aosta,’ formed part of the Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia, Mussolini’s contribution to Operation Barbarossa. The CSIR was part of Army Group South, which invaded the Ukraine in June 1941. After the Axis advance ground to a halt in December, Hitler planned an offensive for the following summer. It was codenamed Operation Braunschweig or ‘Brunswick.’ The offensive, which began on June 28, 1942, enjoyed early success, although supply problems quickly became apparent. The CSIR reached the Don River later in the summer, but their assault stalled on Aug. 20. The 3a Reggimento ‘Savoia Cavalleria’ was sent to the front line to revitalize failing morale. Under the command of Colonel Alessandro Bettoni Cazzago, the 3rd Cavalry Regiment was ordered to take Hill 213.5 near the village of Izbushenskiy, six miles from the confluence of the Don and Khopyor Rivers.

The Italian officers enjoyed a formal regimental dinner on the eve of the dawn attack. Meanwhile, two battalions of the Red Army’s 812th Siberian Infantry Regiment made use of the natural cover afforded by the rolling countryside and dug in.

Before sunrise on Aug. 24, a cavalry recon patrol discovered the Siberians in their fortifications. Shots were exchanged. Bettoni Cazzago had about 650 men under his command divided into five squadrons. Against him were approximately 2,000 Soviet troops with a battery of artillery in support. Cazzago immediately ordered his machine gun squadrons to dismount and form a defensive line, while the 2nd Squadron, under Captain Francesco De Leone, mounted and moved off to the right, where they were able to use the uneven terrain to outflank the Soviet troops. As the Siberians advanced, the Italians charged them from the side, using pistols, grenades, and sabres as they swept across 500 yards of enemy lines. The charge had limited success and left 2nd Squadron cut off behind enemy lines. Bettoni Cazzago now sent 4th Squadron forward in a dismounted charge, a counter-attack that temporarily stalled the Siberian advance and allowed the remains of 2nd Squadron to regroup and charge through the Siberian lines to relative safety.

The Soviets retreated from their advance positions, which were occupied by 4th Squadron, but the Italians were still heavily outnumbered and the battle remained in the balance. Bettoni Cazzago ordered 3rd Squadron, under Captain Francesco Marchio, to attempt to outflank the communists to the left as 1st Squadron launched a second dismounted charge. 3rd Squadron was unable to outflank the enemy and charged with all remaining riders. The cavalry took heavy casualties, but the attack tipped the scales of the battle — the Siberians either ran or threw up their arms in surrender. After six hours of battle, approximately 900 Siberians surrendered and a battery of field guns along with numerous machine guns and mortars were captured. Only about 35 Italians were killed, with double that number wounded. Close to 150 horses were lost.

Mounted Green Berets

The United States’ response to 9/11 is well-known: On Sept. 20, Washington issued ultimatum to Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban. It ordered the regime to hand over the al-Qaeda leadership responsible for the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, including the faction’s founder Osama bin Laden. Kabul refused. Six days later, seven members of the CIA’s Special Activities Division was inserted into the Panjshir Valley, north of Kabul. They linked up with General Abdul Rashid Dostum, head of the anti-Taliban United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan (better known as the Northern Alliance), and prepared the way for air strikes and the insertion of American special forces into the region. By Oct. 7, U.S. warplanes began targeting Taliban and al-Qaeda positions across the country. On Oct. 19, Operational Detachment Alpha 595 of the United States Army Special Forces (better known as the Green Berets) deployed to the Darya Suf Valley. The team of 14 was led by Captain Mark Nutsch (also known by the pseudonym ‘Mitch Nelson’) and included two attached United States Air Force combat controllers. Nutsch and five of his A-team were with Dostum for the successful assault on Bishqab on Oct. 21 and on Cobaki the following day. Dostum’s cavalry charged in both engagements, but the shell-shocked defenders offered little resistance before fleeing.

By the middle of the afternoon of Oct. 23, Dostum had deployed his men half a mile away from the Taliban defences south of Chapchal, 75 miles from Mazar-i-Shariff. He had 600 mujahideen divided into six companies (three mounted and three on foot), all of which took cover behind six hills to the south-east. Machine guns set up on the high ground provided cover. The Taliban force of about 1,000 men had dug a trench approximately 100 yards long, bookended by two ZSU-23 self-propelled anti-aircraft guns with three tanks to the rear. Nutsch and his Green Berets were joined by three CIA officers, one of whom was Mike Spann, who would later be killed at Qala-i-Jangi. The combat controllers ordered the air strike under cover of which Dostum’s cavalry would charge while his infantry outflanked the trench on both sides. As the mujahideen climbed up the rear slopes of the hills and the fighter jet dropped its bombs, the horsemen descended the forward slopes and broke into a gallop. The Taliban opened up with all of the weapons at their disposal: small arms, infantry support weapons, tanks and anti-aircraft guns.

With 800 yards still to cover, Dostum discarded the original plan and led a full frontal combined cavalry and infantry charge, the Green Berets and CIA operators close on his heels. The cavalry fired AK-47s and RPGs from their saddles as they rode; the infantry ran behind. About halfway across the undulating ground, the charge stalled, with half of Dostum’s men having been wounded or taken cover. Dostum leapt off his horse and charged ahead on foot, urging his men to join him as he ran. Horse and foot formed a single line and advanced together. As the Northern Alliance rallied, the Taliban wavered. When Dostum’s line closed to within 20 yards of the trench, the Taliban broke and fled. Casualty estimates are unclear as the Northern Alliance took no prisoners. By the end, about 120 Taliban soldiers lay dead; fewer than a dozen of the attackers were killed along with an unknown number of horses.

In each of these actions – Huj, Izbushenskiy, and Chapchal – cavalry successfully charged a force with both superior numbers and superior firepower, testimony that the greatest effect of the cavalry charge is not its physical force, but its psychological impact. The answer to the question of the date of the last cavalry charge is most likely that it has yet to take place, somewhere on a future 21st century battlefield.

Rafe McGregor is the author of nine books, including Bloody Reckoning, the crime thriller that introduces Captain Garth Hutt DSO CGC of the Special Investigation Branch, Royal Military Police. Rafe lectures at Leeds Trinity University and can be found online at @rafemcgregor.

Rafe McGregor is the author of nine books, including Bloody Reckoning, the crime thriller that introduces Captain Garth Hutt DSO CGC of the Special Investigation Branch, Royal Military Police. Rafe lectures at Leeds Trinity University and can be found online at @rafemcgregor.

Further Reading

- The Marquess of Anglesey, A History of British Cavalry 1816-1919 Volume 5: 1914-1919 Egypt, Palestine & Syria (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1994)

- Giovanni Messe, La guerra al fronte russo (Milan: Ugo Mursia Editore, 2005)

- Doug Stanton, Horse Soldiers: The Extraordinary Story of the Special Forces Who Rode to Victory in Afghanistan (London: Simon & Schuster, 2009)

What about the charge of the 15th Indian (Imperial Service) Brigade consisting of Sherwood Yeomanry, Mysore Lancers and Jodhpur Lancers on 23 Sep 1918 at Haifa.

Re: Affair at Huj, the actual charge and subsequent capture of Beersheba was conducted by the Australian Light Horse WGTJD (We get the job Done) Regiments. Ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Beersheba_(1917)

Absolutely, Lint. I was really annoyed at this gaff they made. Typical Euro-centric rubbish.

what about this one? Charge near Borujsko – the last combat charge of the Polish Army cavalry carried out by the 1st Warsaw Independent Cavalry Brigade on March 1, 1945 [1]. Currently, the village of Borujsko is called Żeńsko.

The lighthouse regiment charged Beersheba and is regarded as one of the finest and last real calvaycharges in wartime https://www.awmlondon.gov.au/battles/beersheba

And it was carried out by ANZAC cavalry (Australian and New Zealand), not by the English.

Who wrote this drivel?

The charge on Beersheba was carried out by ANZAC forces (Australian and New Zealand light horse) NOT English forces.

This is typical of the Euro-centric mentality that thinks the rest of the world doesn’t exist.

Check your basic facts before publishing your articles.

If you get such basic facts wrong in this battle, how do we know you haven’t mucked up the facts in other articles.

PS if the facts aren’t corrected I shall be drawing attention to your monumental gaff on social media.