“While serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment, the 22-year-old future U.S. president touched off a global conflict that would ultimately herald the rise of the British Empire.”

By George Yagi Jr.

GEORGE WASHINGTON is remembered as the “father of his country.” His very name evokes the image of a general leading the Continental Army to victory against the hated redcoats during the American Revolution. Yet many Americans forget that before becoming the hero of the War of Independence, Washington was a fervently loyal British provincial officer, and one who would play a key role in the Crown’s imperial ambitions in North America. In fact, while serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment, the 22-year-old future U.S. president touched off a global conflict that would ultimately herald the rise of the British Empire.

While Lexington Green may have witnessed “the shot heard round the world” in 1775, the Battle of Jumonville Glen in 1754 marked the shot that “set the world on fire.”

The Fight for Ohio

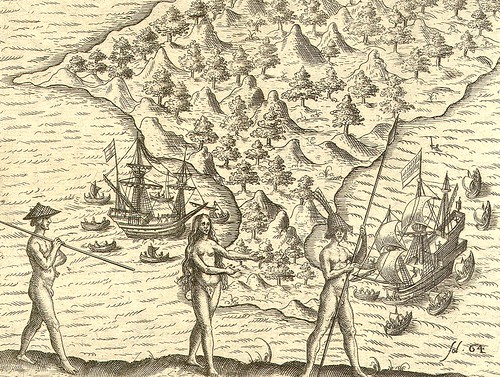

In 1753, Britain and France were at the crossroads of another war, with both powers laying claim to the Ohio River valley deep in the wilderness of North America.

As the French busied themselves constructing forts in the disputed region, Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, received instructions from Whitehall on Aug. 20 of that year ordering him to establish outposts to counter those of the King’s rival. According to London, any attempt by France to prevent the establishment of British fortifications in the Ohio Valley was to be viewed as a “hostile act.” Conversely, if any French forces there refused to depart, they were to be driven away by force.

Dinwiddie’s first move was to dispatch a young Major named George Washington to deliver a message to the French requesting that they peacefully withdraw to Canada. While it was obvious the appeal would be ignored, Washington was also to gather intelligence during his travels for a forthcoming military campaign.

Having completed his mission as emissary, Washington, now a lieutenant colonel, received fresh orders from Dinwiddie in January of 1754: He was to head back to the wilderness to reinforce a British post already under construction at the strategically vital forks of the Ohio at what is now Pittsburgh. His orders read:

You are to use all Expedition in proceeding to the Fork of Ohio with the Men under Com’d and there you are to finish and compleat in the best Manner and as soon as You possibly can, the fort w’ch I expect is there already begun by the Ohio Comp’a. You are to act on the Defensive, but in Case any Attempts are made to obstruct the Works or interrupt our Settlem’ts by any persons whatsoever You are to restrain all such Offenders, and in Case of resistance to make Prisoners of or kill and destroy them.

First Contact

It would take weeks for Washington and his small detachment of soldiers to reach their objective. It turned out that the French had beat them to it.

On April 17, a column of 500 enemy troops arrived at the partially constructed outpost, which had been dubbed Fort Prince George. With a garrison of only 40 volunteers at his disposal, the commander, Ensign Edward Ward, immediately surrendered the fort.

Arriving at Wills Creek three days later, Washington learned from Ward and his men that the French had taken possession of the stockade. He was further informed that the enemy forces comprised of “a Body of French consisting of upwards of one Thousand Men, who came from Venango with Eighteen pieces of Cannon, Sixty Battoes, and three Hundred Canoes.” Despite the dismal odds against him (he commanded only 180 men), Washington called for a council of war and decided to press onward. At the same time, he also received assurances of support from local native Chief Tanaghrisson, the Half King, who was a known British ally.

Maneuver

Yet the Seneca chief, who had no more than 12 warriors under his command, had his own agenda. Having openly supported the British in the Ohio Country, even going so far as to plant the first log of Fort Prince George, Tanaghrisson’s reputation among natives in the region was in tatters now that the French had arrived in force.

The Half King, however, would get his chance for revenge. On May 27, news arrived that a detachment of French soldiers had bivouacked just a few miles from the fortified British encampment at Great Meadows, which had been christened Fort Necessity. Alarmed by the revelation, Washington dispatched a force of 75 men to search for the enemy between the camp and the Monongahela River. Later that evening, a messenger from the Half King appeared with word that the French were located seven miles northwest of Washington’s position instead. Realizing his earlier mistake, Washington quickly organized a party of 40 men and set off to meet the Half King in “heavy Rain, and a Night as Dark as it is possible to conceive.”

On reaching the Indian camp before sunrise, Washington conferred with the Half King, who offered to accompany the inexperienced colonial in his first battle. With the help of several warriors, the French detachment numbering 35 could be overwhelmed. The combined force encircled the unsuspecting Frenchmen who were preparing breakfast, with the Virginians posting themselves above the hollow and the warriors blocking their escape. The French discovered they were being surrounded and a firefight erupted.

Shots Fired

Who pulled the trigger first is unknown, but the consequence of the brief clash would have global ramifications. While the opposing forces exchanged musket volleys, the wounded French commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville, called for a ceasefire. With the aid of an interpreter, the enemy officer tried to convince Washington that his mission was a peaceful one: To deliver a letter asking the Virginians to leave the Ohio, which was considered to be the domain of the King of France. As Washington examined the document, the Half King seized the initiative. “Thou art not yet dead, my father,” he said as he advanced on the wounded officer. With a mighty blow from his tomahawk, the Half King dashed Jumonville’s skull open, and washed his hands with the Frenchman’s brains. His accompanying warriors followed suit and began killing and scalping the enemy wounded, with the exception of one soldier who was saved by Washington. Tanaghrisson hoped the shocking display would salvage his reputation among local tribes; it horrified the Virginian colonel.

Fallout

The massacre would return to haunt Washington. On the evening of July 3, Washington was forced to surrender his headquarters at Fort Necessity to an army of 700 enemy soldiers and native allies. Unfamiliar with the French language, and accompanied by a poor interpreter, Washington unwittingly signed a confession stating that he had assassinated Jumonville, who was described as an “officer carrying a summons… to prevent any establishment on the lands of the King.”

It was a propaganda triumph that only strengthened the French position. Sir Horace Walpole summarized the entire incident as, “A volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire.”

The World On Fire

From this minor skirmish deep in the American wilderness, war would soon spread across the entire globe. While Britain and France struggled for world domination, allies on both sides quickly entered the fray including Austria, Prussia, Russia, Sweden, Spain, and numerous German principalities. Far flung colonial possessions in the Americas, Africa, India, and the Philippines became warzones. Soon after the battle at Jumonville’s Glen, and thrilled with his first taste of combat, Washington wrote to his younger brother John, “I can with truth assure you, I heard Bulletts whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound.”

Without realizing it at the time, the young Virginian had unleashed a conflict of immense consequence. If the American Revolution had never taken place, Washington would be remembered as the man who started the first true world war.

Without realizing it at the time, the young Virginian had unleashed a conflict of immense consequence. If the American Revolution had never taken place, Washington would be remembered as the man who started the first true world war.

Dr. George Yagi Jr. is a historian at California’s University of the Pacific. To learn more of Washington and the Seven Years’ War, see his latest book, The Struggle for North America, 1754-1758: Britannia’s Tarnished Laurels. Follow him on Twitter @gyagi_jr

Pittsburgh is spelled with an “h” on the end

Corrected. Thanks