“Although the Continental Army began the American Revolution as a mob of amateurs, by 1780 it had evolved into a European-style fighting force capable of standing up to the best King George could throw at it.”

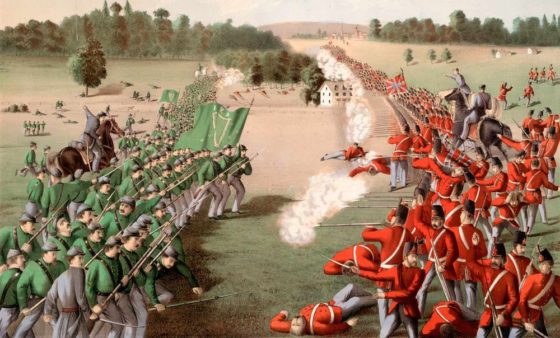

ONE OF THE ENDURING MYTHS of the War of Independence is that the mighty British Army was defeated by liberty-loving American farmers and settlers who made up for their lack of military experience with sheer pluck and determination.

According to the popular narrative, patriot woodsmen sniping from behind rocks and trees decimated the orderly ranks of redcoats who were clearly more at home on the parade squares of Europe than the wilderness of the New World.

While such lore certainly makes good fodder for Hollywood blockbusters, events didn’t really play out that way. Although the Continental Army began the fight for independence as a mob of amateurs, by 1780 it had evolved into a bonafide European-style fighting force capable of standing up to the best King George could throw at it.

In honour of July 4, we here at MHN thought we’d explore other remarkable facts about the United States’ first army.

American regulars? Perish the thought!

Initially, the Continental Congress was against the formation of a national army. Many of the founders looked upon the professional soldiers of Europe with disdain, likening them to either forced men or mercenaries. Others feared that a standing American army might one day become an instrument of tyranny — the very thing the patriots said they were fighting against. Instead, the rebellion’s leadership expected individual colonies to fend off the enemy with their own citizen militias, with help from a corps of elite “provincial regiments.” Following the clashes at Lexington and Concord, Congress quickly changed its tune. On June 14, 1775, the national legislature placed the Massachusetts militia under its authority and ordered the establishment of 10 additional companies of infantry and riflemen. The following day, it named a 45-year-old Virginian by the name of George Washington commander-in-chief. By war’s end as many as 175,000 soldiers had served in the Continental Army, although at any given moment troop levels never exceeded 20,000 men.[1] At some points in the war, it dwindled to fewer than 5,000 soldiers![2]

Help wanted

At first, Congress stipulated that volunteers to the new army would serve for just one year. By 1777, that limit was raised to three years and later extended ‘for the duration of the war.’ Regiments accepted volunteers as young as 16 years of age, and even 15 with parental consent. One artilleryman by the name of Jeremiah Levering was reportedly as young as 12 when he signed on to fight. [3] While Congress lacked the power to enforce conscription, many states relied on drafts to fill their quotas to the Continental Army.

Foreign weapons

Initially, America’s first army was ill-prepared for war. Although most settlers in the 13 colonies owned their own squirrel guns and fowling pieces, many regular units lacked the standardized weapons that were the hallmark of professional armies. Muskets, like the French-made Charleville models 1763 and 1766, were eventually purchased from abroad. More troubling still was that Washington’s army began the war with virtually no gunpowder. In fact, the scarcity of this vital war-making resource was an all-consuming obsession for Congress throughout the war.

An army of immigrants

The Continental Army was as diverse an organization as the nation it fought to establish. Within its ranks were Germans, Dutch, Scottish, Irish and of course English volunteers. Up to a tenth of its soldiers were African Americans, both slaves and free men. In fact, one Rhode Island regiment was more than three-quarters black. [4]

Infighting

Despite its diversity, it would be a mistake to believe that this multi-ethnic fighting force was entirely harmonious. In fact, the enmity among soldiers from the different colonies was often palpable. According to historian John Milsop, “the New Englanders resented the southerners, while the southerners resented the New Yorkers.” [5] The author of Continental Infantrymen of the American Revolution quotes soldier-turned-writer Joseph Plumb Martin who observed that the Massachusetts volunteers in his regiment considered the Pennsylvanians and their bizarre customs to be entirely foreign, even “savage” — not surprising during an era in which the average American rarely strayed more than a few miles from his or her birthplace.

From amateurs to professionals

Training for the first Continental units varied in quantity and quality from regiment to regiment. Some outfits benefited from solid instruction at the hands of veterans of the French Indian War; others were scarcely better schooled in warfare than the militia. It wasn’t until Congress hired a Prussian aristocrat named Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben to oversee army training that things improved. The 47-year-old courtier and soldier organized a 100-man touring company that demonstrated proper drill and battlefield tactics to the more amateur Continental regiments. In 1779, he even published a training manual for the army entitled: Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. Von Steuben’s efforts were instrumental in converting the rebellion’s novice soldiers into the professional fighting force that would be needed to beat the British.

Army food

The daily rations for a soldier in the Continental Army certainly looked hearty on paper. Each recruit was promised one pound of beef, salted fish or pork, a pound of bread, three pints of dried peas or vegetables, a pint of milk and a quart of spruce beer or cider. [6] In reality, the availability food depended entirely on the army’s ability to purchase and distribute supplies. Often, units in the field frequently had to do without. “We were absolutely literally starved,” Joseph Plumb Martin later wrote about conditions during the winter of 1779. [7]

Army pay

By 1780, the typical foot soldier in the Continental Army was told to expect about $29 dollars a year [8] – a small fortune by 18th century standards. Yet again, in reality, the pay was nothing short of abysmal. Many of the rebelling colonies maintained separate currencies and exchange rates varied widely. And although the federal government could issue its own money too, Continental scrip wasn’t backed up by gold and was almost worthless. A Continental infantryman’s annual salary was actually equal to about only about three Spanish milled dollars. [9] Worse, because of the ever-mounting war debt, Congress often lacked the funds to even pay this pittance in full and on time. By 1781, the government was effectively bankrupt.

Desertion and mutiny

The lack of steady rations and pay, along with generally poor living conditions and foul weather, often led to shockingly high rates of desertion. During late 1776, as many as a quarter of Washington’s men absconded. More rigid discipline soon helped stem the exodus, but in 1781, chronic pay shortages prompted 2,400 troops from Pennsylvania serving in New Jersey to mutiny. What’s more, loyal troops ordered to quell the uprising actually joined it. Eventually, Washington calmed frayed tempers by promising the men formal discharges but $10 bonuses if they re-enlisted. Only about half took the general up on the offer. The rest went home.

Battles fought

The Continental Army saw action in more than a dozen full-scale, set-piece battles against British troops and their Hessian allies between 1775 and 1783. These included the famous clashes at Long Island, Trenton, Brandywine, Germantown, Saratoga, Monmouth, Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse and finally Yorktown. The Americans won little more than half of the war’s major engagements.

Losses

All told, as many as 8,000 Continental troops died in action during the war; twice that number perished from hunger or illness. A full 25,000 were wounded in combat. In all, nearly 30 percent of American soldiers who took up arms were killed, injured or captured.

From swords to ploughshares

With the war won, Congress moved quickly to dismantle the military, leaving local defence in the hands of the states. By early 1784, all that remained of the Continental Army was a token force of just 80 men! [10] The following year, federal authorities increased the standing army to 700 men — eight infantry companies, known as the First American Infantry Regiment, and two artillery units. [11] Within the decade, the Continental Army was again expanded and renamed the Legion of the United States. One of its first major operations was at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

“Little short of a miracle”

In his famous “Farewell Orders” to the troops on Nov. 2, 1783, Washington offered his parting impressions of America’s Continental Army.

“The disadvantageous circumstances on our part, under which the war was undertaken can never be forgotten. The unparalleled perseverance of the armies of the United States, through almost every possible suffering and discouragement for the space of eight long years, was little short of a standing miracle.”

I live in Idaho and I need help.

i love this site it help me very much in social studies! i love thank you!

how old was the youngest slave fighter in the revolitution