It took James Peter Wolfe less than 15 minutes to defeat the French at Quebec.

And in that brief time, the 32-year old major general handed Britain her greatest victory of the Seven Years War while forever altering the fate of an entire continent. Ironically, at the precise moment of this, his most epic triumph, Wolfe fell wounded in a hail of musket fire. Minutes later, he was dead.

Now, more than 250 years later, the ill-fated general is the focus of another battle – one waged between the nation of his birth and the country he helped create.

According to Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper, the University of Toronto has been locked in a bidding war against a coalition of British buyers for a long lost collection of some of Wolfe’s own personal papers. Despite efforts to keep the prized documents in England, the Canadian school eventually netted the lot for a cool $2.15 million.

The article, which was penned by Brock University historian John Sainsbury, discusses not only the recent feud for the manuscripts, but also Wolfe’s ticklish legacy in modern Canada.

A one-time British colony, Canada has spent much of the post-World War Two era loosening its historic ties with the mother country. Accordingly, during the late 20th Century, most Canadians’ opinion of Wolfe evolved. Once revered as a genuine champion of the empire, the general gradually became something of a historical footnote in North America — so much so that Sainsbury wonders why a 21st Canadian university would even bid for a British general’s papers in the first place.

“There is irony in the fact that the Wolfe letters are leaving the U.K, where Wolfe remains installed in the pantheon of national heroes, to come to Canada, where he’s been relegated to the margins of mainstream historical narrative,” writes Sainsbury. “So, not surprisingly, there has been a bigger fuss in Britain about the ‘loss’ of the manuscripts than there has been in Canada about their acquisition.”

Wolfe’s legacy in North America is further complicated when considering Canada’s bilingual composition. Even to this day, the 1759 conquest of New France is something of a sore point in French-speaking Quebec. In fact, a 2009 commemoration of the 250th anniversary Wolfe’s victory, to be held on the very spot of the famous battle, was cancelled amid a chorus of objections from Francophones. Many in the province claimed the festivities were offensive and only served to open old wounds. Some Quebecois nationalists even threatened violence should the event proceed. To read Sainsbury full article, click here.

WHO WAS JAMES WOLFE?

Think you know the famous “Hero of Quebec”? Here are seven amazing facts about the curious, complex and sometimes-contradictory man behind the legend.

James Peter Wolfe, born on Jan. 3, 1727, was raised in a military family. His father Edward was a colonel in the Royal Marines and later served as a commander in the King’s 8th Regiment of Foot. James entered the service at the tender age of 13 and by 17 he was a major. The following year, he purchased a colonelcy. Young Wolfe first saw action at 16 during the War of Austrian Succession. In 1748, his regiment was rushed from Flanders to fight against Scottish Jacobites at the battles of Falkirk and Culloden.

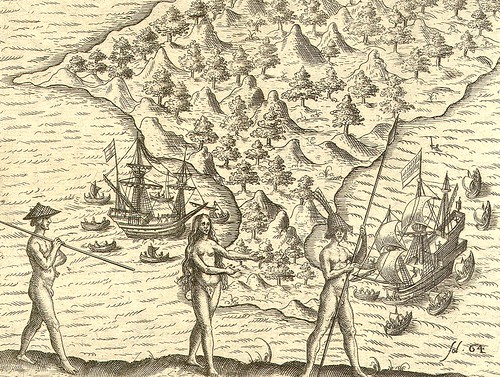

During the Seven Years War, Wolfe commanded troops during the ill-conceived naval descents onto the French coast and also played a key role in the capture of the fortress of Louisbourg in New France (modern day Nova Scotia).

Wolfe earned himself a reputation as a cold-blooded commander on the battlefield. While besieging Quebec he ordered his troops to torch settlements up and down the shores of the St. Lawrence. He even issued a manifesto to the habitants of Quebec threatening them with “fatal consequences” if they aided the French army. Wolfe was also a strict disciplinarian. He often lamented what he saw as a lack of order in the ranks and directed his officers to summarily execute any soldier who broke formation in battle. Despite his penchant for ruthlessness and observance of the King’s regulations, James once flatly refused to carry out orders from a superior to shoot a wounded Scottish rebel considering the act ungentlemanly. [1] Incidentally, that ‘superior’ was supposedly the Duke of Cumberland, aka Prince William.

Despite his stellar military career, James Wolfe didn’t particularly enjoy army life. He once confided in his subordinates that he’d rather have been a poet. While stationed abroad, he spent his off hours studying math, languages and science. On the eve of his great victory at Quebec, he even wrote his mother than he planned to leave the service once the campaign had ended. In 1752, he actually left the army for a time and travelled Europe as an ordinary tourist. In fact, while stopping over at Versailles, a friend in the diplomatic corps arranged for him to meet France’s King Louis XV. [2]

Known as a proficient swordsman, James was actually rather frail and often sick. In fact, he took to his bed for much of the siege of Quebec and had a history of depression. Many officers, and even some in the royal court, considered him crazy. “Mad is he?” quipped King George II. “Then I wish he’d bite some of my other generals!” [3]

With musket balls lodged in his arm, shoulder and chest, James Wolfe continued to issue orders on the Plains of Abraham. Even while drifting in and out of consciousness, the dying commander urged his officers to cut off the retreating French forces.

Wolfe’s remains were shipped back to England where they lie at the Church of St. Alfege in Greenwich. The famous 1762 painting of his death by Benjamin West hangs in Canada’s National Gallery. Schools throughout Canada and the United Kingdom bear his name, as does a town in New Hampshire. A monument stands in Quebec City marking the exact spot on which he died while the cloak he wore in the hours before his death was recently on display at the Halifax Citadel. It was on loan from the Royal Family. Wolfe’s family home in Kent, dubbed Quebec House, is a national historic site.