“Despite the centuries of bad blood between the French and English, there were a few rare moments between 1066 and 1815 when the two nations joined forces to defeat common enemies.”

WAS ANYONE more uneasy about Britain and France joining forces in the Crimean War (1853 to 1856) than Lord Raglan?

Also known as Fitzroy James Henry Somerset, the 64-year-old commander of all of Queen Victoria’s forces in the conflict had spent much of his youth fighting against the French. He even lost his right arm at the Battle of Waterloo.

While in command of the Black Sea expedition, Raglan famously referred to Napoleon III’s troops as “the enemy” and according to some accounts on at least one occasion even instructed his troops to attack the French instead of the Russians! Mistake or not, Raglan’s attitudes informed by centuries of history in which France was England’s mortal foe.

Certainly at present, Britain and France are enjoying the longest period of uninterrupted friendship the two nations have ever known — nearly 200 years and counting. Yet from the Norman Conquest of the 11th Century right up to the fall of Napoleon, the French and English fought each other in more than 20 separate wars. Some of these show-downs lasted several decades. In the 18th Century alone, the cross-channel rivals locked horns in five different major conflicts, as well as a series of smaller dust-ups in their far-flung colonies.

Amazingly, despite the centuries of bad blood between the French and English, there were a few rare moments between 1066 and 1815 when the two nations joined forces to defeat common enemies. Consider these examples:

The Kings’ Crusade (1189 to 1192)

On a number of occasions during the 11th and 12th centuries, the English and French stopped killing each other long enough to focus their lethal energies onto non-Christians in the Holy land.

The third and largest of these Crusades, saw France’s Philip II and King Richard I of England bury the hatchet and join in with the Holy Roman Emperor Fredrick I to rescue the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the Muslims under Saladin. While Richard and Philip won a number of battles together, including some famous ones at Acre, Arsuf and Jaffa, ultimately the coalition of 100,000 European knights and men-at-arms failed to drive Saladin from the Holy City.

After three years of war, the Christian kings negotiated a peace treaty with the Muslims that would grant pilgrims of both faiths access to Jerusalem. Yet the European Crusaders would return six years later to try once more to secure the sacred territories. And in the meantime, England and France resumed their normal state of intrigue and conflict.

Battle of the Dunes (1658)

Perhaps one the strangest episodes in the long and contentious history of England and France took place in June of 1658. That’s when a force of 6,000 troops from Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army along with a fleet of 18 English warships joined 15,000 French soldiers under the command of the celebrated Vicomte de Turenne to wipe out a nest of Spanish privateers at Dunkirk.

The pirates, who had been licensed by Philip IV of Spain, had long been ravaging merchant shipping in the English Channel. France and Spain had already been at war already for 20 years at that point; Cromwell’s Commonwealth of England had little love for Philip either. After all, the Spanish monarch had been harbouring the exiled English monarch Charles II whose father had been executed by the Parliamentarians a decade earlier during the English Civil War.

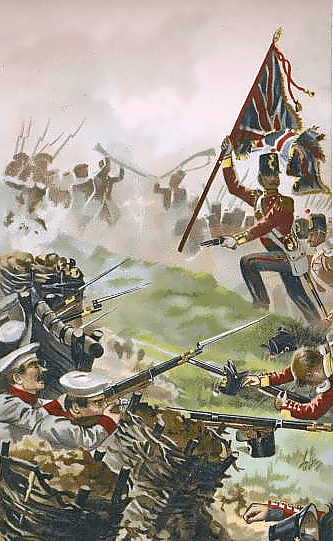

As the Anglo-French army laid siege to the privateer base at Dunkirk, Spain’s formidable Army of Flanders, along with a contingent of French revolutionaries known as Frondeurs and a group of 2,000 English Royalists attacked from the east. The two-hour battle, which took place on the sandy beaches surrounding Dunkirk, saw the English redcoats charge headlong into the Spanish lines, driving the enemy off a line of dunes that dominated the battlefield. By noon of June 14, more than a thousand Spaniards, Frondeurs and Royalists lay dead and 5,000 were prisoners. The defeat sent Spain’s Flanders army reeling. A series of French victories followed forcing to Spain to sue for peace the following year.

War with Holland

Only the byzantine and ever-shifting political alliances of 17th century Europe could produce a war as confusing at the one fought between France and Holland from 1672 to 1678.

The conflict grew out of a number of issues, not the least of which was France’s resentment over an alliance between the Dutch Republic and Spain. After all, France had only years earlier helped Holland free itself from the grip of the Spaniards. King Louis XIV flew into a rage when in 1668, the Netherlands joined both Spain and the hated English in a coalition against the Bourbon monarchy. Not surprisingly, the slighted Sun King turned his army loose on the ungrateful Dutch four years later.

Then came an ironic reversal: England, which itself had helped draw Holland away from France in the first place, became increasingly troubled by the Netherlands’ growing clout and actually entered the war on the side of France. English and French ships combined to challenge the Dutch in massive sea battles off Solbay in June 1672, Schooneveld the following year, as well as Texel in August of 1673. After losing these encounters, England was forced to abandon France and withdraw from the fight. Parliament refused to finance the war further amid growing concerns that King Charles II was trying to return the British Isles to the Catholic fold.

War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718 to 1720)

King Philip V of Spain, growing nostalgic for his empire’s former days of glory, mounted an ambitious campaign in 1717 to recapture lost territories in Italy, including the islands of Sardinia and Sicily.

After a series of successes, Europe’s other major powers: namely Austria, the Holy Roman Empire and both Britain and France (who had just recently inked a bi-lateral alliance of their own) joined a four-way coalition to force Phillip withdraw from the region. Spain resisted and the two-year War of the Quadruple Alliance was on.

The conflict soon spread to the New World and the Caribbean and even saw Spain land a small force of troops in Scotland to assist an ultimately doomed Jacobite uprising there. Facing mounting losses, Philip called it quits in 1720 signing the Treaty of the Hague on Feb. 20. Britain and France remained allies until another war broke out with Spain just a few years later. This time the French refused to participate leaving London’s faith in this new-found cross-channel friendship in tatters. The alliance formally collapsed by 1731 and within a decade the two powers would be fighting once more. They would not come together again until after the Battle of Waterloo.