“Huston’s wish was to let America see and understand the fragile emotional state of many returning vets.”

U.S. ARMY DOCTORS in the Second World War didn’t use the term “post-traumatic stress disorder,” but they knew all about it.

In fact, what was called “battle fatigue,” “combat fatigue” or “combat stress reaction” was commonplace among veterans returning from Europe and the Pacific in 1945.

So when the U.S. military wanted to document the story of a group of soldiers who, with considerable psychiatric help, overcame the condition, it tapped legendary Hollywood filmmaker John Huston to tell the tale. The result was a documentary that was so revealing, military censors eventually tried to prevent its release.

Let There Be Light follows the post-war psychiatric rehabilitation of combat GIs suffering from what was then referred to as psychoneurosis, today known as PTSD.

Huston, who is perhaps best known for his 1941 film noir classic The Maltese Falcon, joined the army after Pearl Harbor. His cameras captured much of the action on Midway Island during the 1942 battle there as well as the intense fighting in the Italian campaign. Let There Be Light was equally hard-hitting.

The documentary pulls few punches as it shows the war’s psychological impacts on the young men who fought in it. Huston’s wish was to let America see and understand the fragile emotional state of many returning vets.

Despite its initial interest in having the story told, the army eventually swooped in to suppress the film just prior to its release. In fact, military officials seized a print of Let There Be Light moments before it premiered in New York in 1946. No other copies were distributed.

The Pentagon claimed the film violated the privacy of the vets appearing in it. Huston wrote later that he believed the military brass feared that movie’s portrayal of the emotionally shattered soldiers might have upended the popular narrative that GIs were fearless warriors who returned from the war better men for the experience.

The film is also notable for its real-life depiction of African-American and white vets freely mingling and interacting with each other — a concept that would have seemed out of place in much of pre-civil rights America. A subsequent reshoot of the movie by military propagandists tried to tell a sanitized version of the story using all white actors, none of them real combat veterans.

In 1980, the army planned to finally make Huston’s original film available, but the master print had deteriorated by that point making it unwatchable. Digital technology has since enabled film historians to restore Let There Be Light to its original quality.

The movie has been released on the Internet and is available for free to anyone.

Annette Melville of the National Film Preservation Foundation, the organization that funded the picture’s restoration, says Let There Be Light has a new found relevance as American combat troops return from Afghanistan and Iraq with many of the same emotional disorders suffered by veterans of previous wars.

“We hope that by making Let There Be Light freely available — and by drawing attention to it — that the courageous documentary will find the audience it was intended to serve,” said Melville in a press release.

To watch Let There Be Light, click on the link below.

(Originally published, May 25, 2012)

Just finished watching the film. Authentic. Memorable. Moving.

Another observation: I am surprised at how articulate typical 20-something GIs were in 1945. I work with people of the same age group today on a daily basis. Not a lot of them are as well spoken as the soldiers appearing in this film.

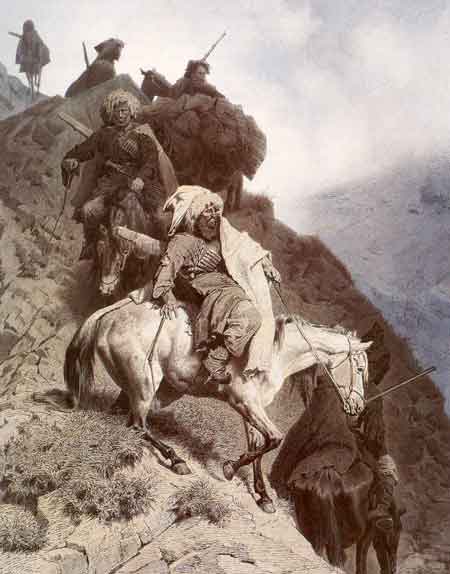

I believe that the photo you are showing was taken during the Korean War (1950-1953). If that is correct then it was obviously not available when John Huston made his film in 1946.

The image itself doesn’t appear in the film. It’s being used here to depict PTSD in general.

Great film, well made, telling a story that should have been made public in 1948 to help everyone understand many soldiers don’t simply come home and pick up where they left off. It still has value and its purpose remains as long there is war.

I agree! Thanks for your note.

First off, thanks for correcting this old brain of mine. For YEARS, I had thought it was John FORD who filmed that (now) famous footage of a hangar being blown up during which he was knocked out. I am unable to view or download the film where I currently am but will endeavor to do so once returning home. It certainly appears to be very interesting and informative.

I believe I read that Ford shot a lot of footage during the war in the Pacific. In fact, I believe he was present at the Battle of Midway, camera in hand. He later was involved in this PTSD film.