“While at the time Berlin and London were slowly drifting to war, the estranged powers, along with Italy, did manage to find a common enemy in Cipriano Castro.”

LAST MONTH, Venezuelans bid farewell to Hugo Chavez after the polarizing, 58-year old leader lost a long running battle with cancer. A one-time military officer and self-described 21st Century socialist, Chavez rode a wave of populism into power in 1999 following imprisonment for his part in a 1992 coup d’état.

Once elected, the left-leaning Chavez rewrote his nation’s constitution, imposed strict controls on Venezuela’s oil industry, curtailed democratic freedoms and generally thumbed his nose at the United States at nearly every opportunity.

His bombastic denunciations of Washington were legendary, earning him as much scorn from the Oval Office as his selling of oil to Cuba and his diplomatic support of Iran. He also was known for blasting the Catholic Church and heaping praise on Marxist guerrillas in neighbouring Columbia.

The Bush Administration confirmed its interest in seeing Chavez deposed. In fact, the thrice-elected Venezuelan leader even implicated Washington in a failed 2002 uprising that briefly removed him from power.

Interestingly enough, Venezuela has something of a tradition of producing these sorts of larger-than-life autocrats, particularly ones that draw the ire of the international community.

Consider Jose Cipriano Castro, a military strongman who sized the presidency in 1899 (exactly 100 years before Chavez’s rise). Castro would rule Venezuela for nine years, go toe-to-toe with a trio of European superpowers and even wage a brief war against Holland before being chased into exile.

Born in a remote village in the Andes in 1858, Castro was the son of a moderately successful farmer. In his early life, he worked as a clerk, a cowboy, an innkeeper and even a newspaper editor before joining the military at the age of 28.

After taking part in an anti-government rebellion, Castro fled to Columbia where he amassed a small fortune as a cattle baron, all the while building his own private army. In October of 1899, he marched his legion across the border and snatched control of the capital, naming himself president.

Following his rise, Castro’s Venezuela descended into chaos for years as rival factions vied to unseat him. Much like Chavez, Washington denounced Castro as a thug, with President Theodore Roosevelt’s own secretary of state describing him as a “crazy brute.” [1]

His refusal to compensate European businesses for losses suffered amid his tumultuous first years in power eventually led to a military showdown with Britain, Germany and Italy.

While at the time Berlin and London were slowly drifting to war, the estranged powers, along with Italy, did manage to find a common enemy in Cipriano Castro.

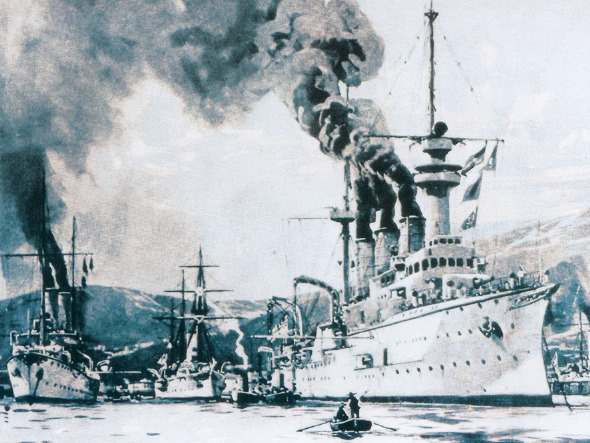

In December of 1902, three nations jointly dispatched a fleet of warships to bring the upstart Latin American dictator to heel. The squadron of Italian, British and German gunboats, destroyers and cruisers soon arrived on station in the Caribbean, where they established a tight blockade and easily seized the whole of the Venezuelan navy, such as it was. Germany, unable to tow the two vessels it captured to the nearest friendly port simply destroyed them.

A piqued Castro threatened vengeance against European nationals in the capital, at which point the joint force put troops ashore to evacuate their citizens. German and British vessels even bombarded a Venezuelan fort for good measure. While the British soon called off their ships, German vessels would continue to attack forts along the coast for the next few weeks. That’s when the situation escalated.

Despite its dislike for Castro, Washington suddenly found itself intervening on his behalf.

American voters were growing uneasy at the prospect of Europeans once again bringing military force to bear in the Western Hemisphere. Newspaper editorials pressed the White House for action. Roosevelt quietly feared Berlin might even use the crisis to justify setting up a permanent military presence in Venezuela. Accordingly, the White House ordered the American fleet into the Caribbean as a check on further German aggression. Meanwhile the U.S. quickly brokered a deal in which Castro would divert a portion of tariffs to recoup the losses suffered by Europeans businesses. Roosevelt even signalled that America was prepared to fight Germany if the Kaiser didn’t cease and desist.

The dictator survived — his reputation was even elevated for standing up to the imperialists.

Unfortunately, within six years, Venezuela would be neck deep in a crisis with yet another European power: The Dutch.

In 1908, Castro expelled the Dutch ambassador from Venezuela over suspicions that Holland was harbouring the president’s political opponents on the nearby island of Curacao. Incensed, the Dutch ordered its navy to take punitive action. Venezuelan vessels in port in the Netherlands were impounded and Holland sent a gunboat and two cruisers to the Caribbean to punish Castro’s regime. The three ships prowled the coastline of Venezuela grabbing both naval and merchant vessels. In the middle of this new crisis, Castro left his country, ostensibly to receive medical treatment for an undetermined illness — some speculate it was Syphilis. [2]

With the president out of the country, Venezuela’s lieutenant governor (and a political ally) named himself president and began overtures to the Dutch. Castro was through. Over the years, he plotted various plans to regain power; all of them failed. He died in exile in Puerto Rico in 1924.

As usual, very interesting.