“The term ‘pyrrhic victory’ is named for the ancient ruler of Epirus, King Pyrrhus, who went down in history for winning a string of major battles against Rome and Carthage but still losing the war he was fighting.”

TEN YEARS AGO today, the U.S. led a so-called “coalition of the willing” into Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

While the “Shock and Awe” campaign that followed decimated the Iraqi army and toppled the oppressive Ba’athist regime in Baghdad, America’s victory came with a heavy price tag — too heavy according to many.

For the next eight years, U.S. troops would be bogged down fighting an intractable insurgency. The occupation would also sap the treasury and ultimately leave the United States diplomatically weakened and politically divided. All week, the U.S. media has been awash with stories and commentary marking the anniversary of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The articles have weighed everything from the Bush Administration’s shaky case for war to the toll of the conflict in terms of both blood and treasure. Many of these stories have concluded that the defeat of Saddam Hussein, while ridding the planet of one of the modern era’s most hated despots, represented what could best be described as a pyrrhic victory for the United States and its allies – the cost of triumph over Saddam was simply too high.

The Pyrrhic War

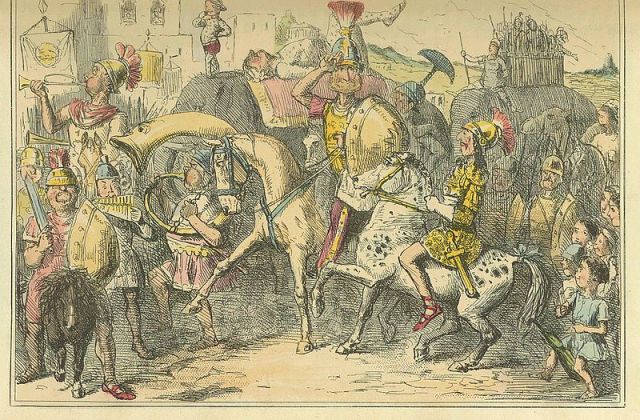

The term “pyrrhic victory” is named for the ancient ruler of Epirus, King Pyrrhus, who went down in history for winning a string of major battles against Rome and Carthage but still losing the war he was fighting.

The conflict, known as the Pyrrhic War, began in 281 BCE when the 38-year-old monarch from western Greece offered to lend his support to Tarentum, a city-state in southern Italy at odds with the burgeoning Roman republic.

Pyrrhus’ interest in protecting the people of Tarentum was based on more than mere altruism — by thrashing Rome and saving small city, the monarch would gain a foothold in Italy from which he could realize his own imperial ambitions.

The following year, the would-be emperor crossed the Adriatic with an army of 25,000 men and a secret weapon: 20 war elephants on loan from Ptolemy II of Egypt.

Pyrrhus sent word to the Romans that he was in Italy with his army to mediate the dispute with Tarentum. Rome refused all invitations to the peace table and instead attacked with 30,000 men.

The two armies met at Heraclea, just west of Tarentum. The ensuing battle saw Greek phalanx and Roman legion fight each other to a bloody stalemate.

At one point, fearing for his safety, Pyrrhus traded his distinctive royal battle armour for the less conspicuous panoply of one of his lieutenants. It was a fortuitous decision. The Romans, assumed the figure in the gilded breastplate was the enemy king and slew the aide.

Believing their rule was dead, the Epirians panicked. Only by stripping off his helmet and riding along the Greek lines was Pyrrhus able to restore his soldiers’ confidence.

With the Romans pressing the advantage, the Hellenic monarch finally unleashed his elephants. The legions and their supporting cavalry were reportedly terrified by the enormous creatures, the likes of which they had never seen, and stampeded from the field. Some estimates peg the Roman losses at 15,000. The triumphant Greeks sustained as many as 11,000 dead and wounded. Although the defeat was a stinging one for Rome, to the victorious Pyrrhus who was operating far from his homeland, the losses were far more devastating. In fact, the king was suddenly so short handed, his bid to march on Rome itself would have to be abandoned.

Two years later, the Greek ruler rebuilt his army using Macedonian troops and other units from the Ionian Peninsula. With 40,000 men under his command, Pyrrhus set out again to conquer Italy. A two-day battle ensued at Asculum. Once more, the elephants broke up the Roman line and sent the legions scurrying. Rome left 8,000 dead or wounded behind. The Greek casualties were much lighter at nearly 4,000. Yet the hard-fought battle had again exhausted Pyrrhus.

“One more victory like that and we’re finished,” he famously declared.

Unable to press on, the Greek king petitioned Rome for a ceasefire. They refused. He next sought an alliance with Carthage but was again rebuffed. Worse, both the Romans and Carthaginians actually joined forces against the Epirian ruler.

Unable to maintain his territories in Italy, Pyrrhus set out instead to snatch new lands on Sicily. After winning repeatedly against the Carthaginians there, the cost of his victories once more proved too great — Pyrrhus withdrew.

A final gambit in 275 BCE saw the Greek ruler with 20,000 remaining troops suffer humiliation at Maleventum. Pyrrhus soon quit Italy entirely with small a fraction of the men he had set out with years earlier. He died three years later in Greece after being struck on the head by a terra cotta roofing tile.

While Pyrrhus had won almost all of his battles against the Rome and Carthage, he gained nothing in more than six years of war. Fruitless victories from then on would bear his name.

Other Pyrrhic Victories

Two weeks ago, we threw it out to this blog’s twitter followers to come up with some examples of other pyrrhic victories from military history. Here’s what you had to say:

@Londinium88 suggested the Battle of Bunker Hill. The June 17, 1775 clash was fought between between American minutemen and British troops at Charlestown in Boston. It saw a vastly superior force of redcoats march on rebel positions on Breed’s Hill and nearby Bunker Hill. The 3,000 Tories managed to dislodge the patriots, but only after taking 30 percent casualties themselves. The British did win the high ground, but the rebels learned that they could stand fast in the face of the thin red line.

@allanholloway rightly added the Battle of Pearl Harbour to the list. While it’s true that the Japanese sank 19 American ships in the early morning surprise attack, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto presciently realized that the raid had actually sealed Japan’s fate. “I fear all we have done is awaken a sleeping giant,” he supposedly said following the battle.*

“What a massacre! And without result,” was what Marshal Ney of France reportedly said after surveying the carnage following France’s hollow triumph over Russia at Eylau in East Prussia in early February 1807. @LandOfHistory suggested we add the two-day battle, which cost both sides as many as 15,000 casualties each, yet had little effect on the War of the Fourth Coalition. In September of 1812, France would experience another pyrrhic victory against the Russian Tsar at Borodino. While inflicting nearly 45,000 casualties on the Russian army and virtually opening the road to Moscow, Bonaparte could ill-afford the grizzly butcher’s bill – 30,000 French dead. Typhus had already cut his 600,000-man army down to 150,000 in three months. This, plus the staggering losses at Borodino, would make it impossible for the French Emperor to subdue Russia. By the time the first snows of winter had arrived, the remnants of Napoleon’s army would be in full retreat. Thanks to @LandofHistory for both of these suggestions.

@BriW74 offered up two other examples of pyrrhic victories: The Lakota triumph at Little Big Horn in 1876 and the Zulus’ win at Isandlwana in 1879. In both cases, indigenous warriors completely wiped out detachments of much more advanced ‘modern’ armies, yet in each example, the victors were soon overpowered and subjugated by superior enemies. Thanks for the suggestions.

* NOTE: While Yamamoto’s remarks appeared in both the films Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and the abysmal Pearl Harbor (2001), it’s not clear if he ever actually uttered those words.

Guilford Court House.Cornwallis won the battle and retreated to Yorktown.The rest is,well the rest.

Thanks for that!

Thanks for letting me camp out in your blog for a little while today. I had a great time and tried to leave my campsite as good as when I arrived. I’ll be back in a couple of weeks!