THE UNITED STATES military is abandoning its recently-adopted pixelated camouflage uniforms, according to the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

The drab grey digital scheme, known as the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP), will be discarded after only eight years following mounting evidence that the splotches makes soldiers more visible, not less.

The article pulls few punches in its appraisal of the move to adopt the pattern in 2004.

“Army brass interfered in the selection process, choosing looks and politics over science,” reports the paper.

And while the Pentagon spent $5 billion on the much-heralded uniforms, some of the earliest attempts to conceal soldiers on the battlefield were considerably less expensive.

EVERYONE IN KHAKIS

During the 1857 Indian Rebellion, British regulars dyed their summer white tunics with coffee, tea and even ink to make them less conspicuous in the field. The resulting off-brown shade became known as khaki, a derivative from the Hindi word for “dusty”. The trend quickly caught on with units throughout India and by the 1880s, soldiers across the British Empire had replaced their iconic red coats with khaki tunics.

The American army soon followed suit, replacing the long-favoured blue jackets, with a tan uniform.

Not surprisingly, this rush to make soldiers less conspicuous coincided with the advent of more accurate, longer range rifles and the machine gun.

Prior to these breakthroughs in firearm technology, generals actually wanted their troops to stand out in combat. Bright coloured uniforms, shiny buttons, oversized hats, and ornate flags and banners were supposed to intimidate the enemy. The garish colours also enabled commanders to identify their regiments on distant smoke-clouded battlefields. The risk associated with marching in the open en masse wearing parade-square finery was mitigated by the fact that smooth-bore muskets were notoriously inaccurate and largely useless beyond 100 yards.

With the emergence of more accurate guns and rapid-fire weaponry the need to stay out of sight suddenly became matter of life and death.

By the end of the 19th Century, many European armies adopted more subdued colours for their uniforms. While Britain went with khakis and browns, the Germans dropped Prussian blue in favour of field grey. Amazingly, some armies bucked the trend.

When in 1911 a plan was tabled to replace the French infantry’s bright blue tunics and brilliant red pantaloons with something a little less striking, traditionalists cried foul. “Abolish red trousers?” the French minister of war scoffed, “France is red trousers!” [1]

Within three years, thousands of French soldiers would pay dearly for such stubbornness — bright colours made soldiers easy targets for machine gunners. Soon, France would soon lead the way in the art of concealment. By 1915, the French founded a camouflage department within the army, and even coined the very word camouflage. [2]

CALLING ALL ARTISTS

By the First World War, specialists known camofleurs were joining the ranks of most of the armies of Europe. These early practitioners consulted artists, psychologists and naturalists for advice on hiding everything from troops and vehicles to fortified positions from aerial observers, snipers, and artillery spotters.

Among the first camofleurs were painters, particularly those who worked in the areas of cubism and impressionism. The abstract forms and colours of these styles inspired many early camouflage patterns. In fact the French painter Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola headed up his country’s camouflage department in 1915. Later, Britain would turn to painters like Roland Penrose and Frederick Gore to design its patterns. [3]

Early camofleurs also poured over books like the American naturalist Abbot Thayer’s work Concealing Colouration in the Animal Kingdom. The book explored how drab colours, spots, speckles and stripes help wildlife evade predators in nature. [4]

Soon all the armies of the First World War were borrowing a page form this book and trying not to be seen. Case in point: Britain ordered 7 million square yards of camouflaged netting to hide its gun emplacements.To protect their aircraft, Germans fliers began painting elaborate polygonal speckles known as lozenge patterns on their planes’ wings and fuselages to make them harder to spot. At sea, British and American navies adorned the hulls of their warships and cargo vessels with high-contrast diagonal stripes and geometric shapes. The confusing patterns, known as razzle dazzle, didn’t conceal the vessels, but made it hard for enemy spotters to determine the type of vessel, as well as it’s size, distance and heading. The advent of radar and sonar would render such garish paint schemes obsolete.

WORLD WAR TWO

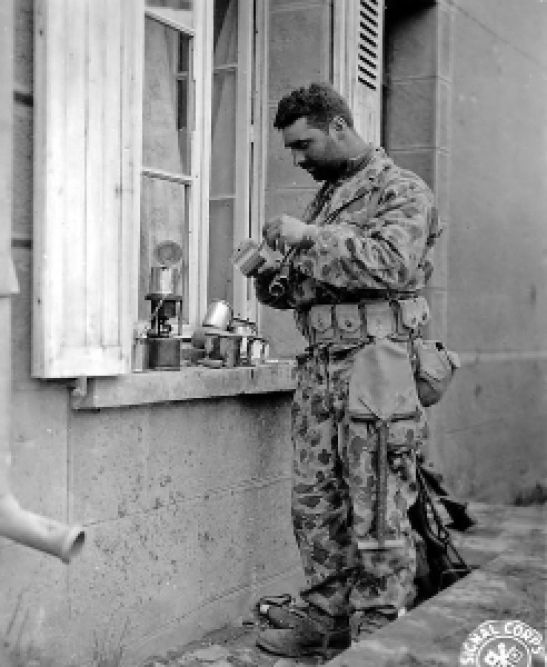

Camouflage techniques would be further enhanced in the interwar years. The ability to weave patterned fabrics enabled militaries to produce full camouflaged uniforms.[5] Germany experimented the most with these techniques in the years leading up to the Second World War, developing a dizzying array of tunics, ponchos, helmet coverings and reversible field jackets in a wide range of patterns and colour schemes suitable for use in almost any terrain or season. Platanenmuster was a speckled pattern, Rauchtarnmuster featured blurred edges, Beringtes Eichenlaubmuster and Eichenlaubmuster were based on oak leaf designs. Initially, camouflage was reserved for elite units in the Wehrmacht or SS, but by the middle of the war, most soldiers were wearing some variety of camouflage.

The Allies too began sending their troops into combat in patterned uniforms. Americans embraced camouflage early in the war, with many units in the Pacific wearing full uniforms featuring a green and brown leopard spotted pattern known later as duck hunter patterns. Some units in the 1944 Normandy campaign were issued similar uniforms. Unfortunately, the U.S. design too similar to one popular with the Germans and GIs wearing these uniforms soon found themselves drawing friendly fire. The suits were quickly withdrawn.

CAMO FOR FIGHTING AND FOR FASHION

Following the Second World War, full camouflage uniforms became widely adopted by the world’s armies and vast resources went into research and development for the best patterns. Everyone from behavioural psychologists, neurologists, zoologists and even Madison Avenue ad men were enlisted to produce modern camouflage patterns such as woodland, tiger stripe, chocolate chip and even the new digital disruptive patterns.

Soldiers haven’t been the only ones sporting camouflage. The use of disruptive patterns has been popular among civilians from the very beginning. Within months of the start of the First World War, Parisian fashion designers, inspired by the striking colours and modern-look of camouflage patterns, integrated similar shades and shapes into women’s fashions.[6]

And in addition to being a big hit among hunters, survivalists and bird watchers, olive drab and camouflage combat gear would go on to become a symbol of both irony and protest during the anti-war movements of the 1960s. Over the next 30 years, camouflage would move from the counter culture to the mainstream with everyone from campus hipsters to pre-school toddlers wearing army-inspired patterns. It’s even become popular among lingerie designers. [7]

Although cutting edge battlefield technologies like infra-red, thermal imaging and even heart beat sensors have made it much easier to locate concealed combatants, a soldier’s first defence is still blending in to the background.

What does the future hold for camouflage? If you’ll pardon the pun – that remains to be seen.

Interesting facts about Camouflage

- Ironically, the Allied air forces found it safer at times not to camouflage their aircraft. During the D-Day landings, British and American fighters, bombers and transport aircraft were all painted with highly visible black and white invasion stripes on the wings and fuselage. This anti-camouflage pattern was intended to make the aircraft instantly recognizable to Allied units, thus preventing friendly pilots and anti-aircraft gunners from firing on them. The British and French used the same technique again during the Suez Crisis of 1956.

- In the 1940s, British illusionist Jasper Maskelyne hoped he could work his magic to conceal Allied troops and fool the Germans. He formed a unit of specialists called the Magic Gang who, during the North African campaign, concealed the entire city of Alexandria Egypt from Luftwaffe.

- Civilians and even children are banned from wearing camouflage in Barbados and Aruba. Cruise lines warn passengers to leave the patterned attire in their suitcases when making landfall on those islands. Camouflage is reserved exclusively for military personnel.

- Canadian forces CF-18s feature phony cockpits painted on the underside of their jets to fool enemy pilots, even if only for a split second.

____________________________________

SOURCES

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_camouflage

2. Ibid

3. http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1906083,00.html

4. Ibid

5. http://www.captaincamo.com/history.html

6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_camouflage

7. http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1906083,00.html

Camouflage Nets provides production from sun rays, Dust, rain show it makes it very important equipment for army. Camouflage Nets in India can be purchased online from many website like raksha supreme.