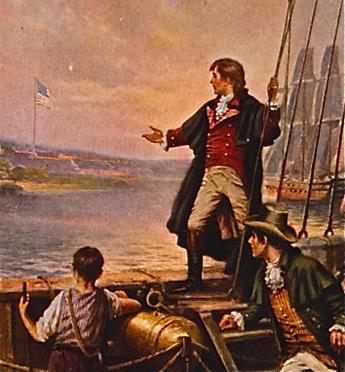

“The prison hulks of Portsmouth and Plymouth, England would become home to thousands of captured enemy soldiers and sailors.”

By Chris Dickon

“MAN TOOK ONE of the most beautiful objects of his handiwork and deformed it into a hideous monstrosity.” So wrote historian Francis Abell in his 1914 book Prisoners of War in Britain, 1756 to 1815.

In it, the author describes the horrendous conditions to be found on HMS Prothée, a captured 64-gun French vessel that had been dismasted and converted into a floating jail for prisoners of war.

Each night, according to Abell, he Prothée’s portholes would be tightly sealed to prevent the inmates from escaping.

“At 6 a.m. in summer and 8 [a.m.] in winter, the port-holes were opened, and the air thus liberated was so foul that the men opening the port-holes invariably jumped back immediately.”

And the hideous monstrosity started another day.

The Prothée was just one of an unknown number, probably approaching 100, of decommissioned warships used by the British as prison hulks between the years 1776 and 1857.

Neutered from a “she” in Abell’s description, it would be mostly used to hold French prisoners of the Napoleonic wars, then American prisoners of the War of 1812 in Portsmouth harbor.

During that war, and in the previous American Revolution, the prison hulks of Portsmouth and Plymouth, England would become home to thousands of captured enemy soldiers and sailors. Depending on who wrote the history, the ships were either light and airy spaces that could accommodate prisoners humanely, or cramped and dank hell holes that held hundreds of men in over-crowded quarters, portions of which were not high enough to allow inmates to even stand upright. The latter description has prevailed.

(Image source: WikiCommons)

Both of the two most prolific autobiographers of those wars, Andrew Sherburne and Benjamin Waterhouse, spent time in captivity, both on shore and in hulks. Conditions in conventional British jails of the late 18th and early 19th centuries ranged from fairly benign to untenable, depending on where one had the good or bad fortune to end up. But the hulks were universally appalling places, devoid of any attempt at basic human decency, the third level of hell.

In his Memoirs of Andrew Sherburne; a Pensioner of the Navy of the Revolution, Written By Himself, the author recounts his life as a 13-year-old American privateer along with his arrival as a prisoner of war in Plymouth in November of 1781. His reaction upon entering the harbor was one of confusion.

“It excited some peculiar sensations to lift up my eyes and behold the land of my forefathers. I must confess I felt a certain kind of reverence and solemnity that I cannot well describe. Yet when reflecting on my situation, and bringing into view the haughtiness of her monarch and government; their injustice and cruelty to her children; I felt an indignant, if not a revengeful spirit towards them.”

He was fortunate, however, to be held in the Old Mill Prison on a windswept promontory in Plymouth Bay rather than in one of the hulks in the harbor.

It was indeed a peculiar gratification to think of entering Old Mill prison. At length we came to the outer gate, which groaning on its hinges, opened to receive us into the outer yard.

Old Mill was a city unto itself, its population a mix of every nationality with which the British had a problem. A philanthropist of the time determined that, though certainly a place of death and disease, the facility was probably among the healthiest of British war prisons. And it was associated with the Royal Naval Hospital in Plymouth, which was deemed to treat prisoners with benevolence.

(Image source: WikiCommons)

Eventually, however, the fortunes of war would take Sherburne across the ocean in one of the prison transports that, though seaworthy, were as bad as the hulks. The notorious Jersey, in New York Harbor, would become his home.

I had just entered the eighteenth year of my age, and had now to commence a scene of suffering almost without a parallel. The ship was extremely filthy, and abounded with vermin. A large proportion of the prisoners had been robbed of their clothing. The ship was considerably crowded; many of the men were very low spirited; our provisions ordinary, and very scanty. They consisted of worm eaten ship bread, and salt beef . . . . at night the hatches were shut down and locked, and there was not the least attention paid to the sick or dying, except what could be done by the convalescent; who were so frequently called upon, that in many cases they overdid themselves, relapsed and died.

Death on the Jersey, according to 1780 inmate and future commander of the USS Constitution, Silas Talbot, was most often the result of dysentery and fever. Men would die at the rate of about 10 per day in the cool months; many more in the summer. They were buried in the banks of Long Island Sound, and stray bones and skulls could often be found scattered on the shore.

Not much had changed by the War of 1812. This time, it became the mission of one Benjamin Waterhouse to “illustrate the moral and political characters of three nations” with a tour through the dreadful war prisons of Canada and England in his Journal of A Young Man of Massachusetts. Purported to be “written by himself,” the book was an apparent conflation of the stories of a number of young men as strung together by Waterhouse, a naval surgeon who would go on to co-found the Harvard University medical school and share in the development of the small pox vaccination.

The composite Waterhouse arrived in Portsmouth harbor by prison transport across the ocean in October 1813. He and his fellows were moved to a hulk that he described as bereft of space to exist and with the full aroma of diarrhea.

God of mercy cried I, in my agony of distress, is this a sample of the English humanity we have heard and read so much of from our school boy years to manhood? If they are a merciful nation, they belong to that class of nations ‘whose tender mercies are cruelty’.

Eventually, Waterhouse was transported to the prison hulk Crown Prince on the River Medway in Chatham, which was not so bad when compared to other vessels. But the respite was short lived, and he was moved to the hulk Chatham where day-to-day life was endangered by the roughest of fellow prisoners and the presence of typhoid and small pox.

The rate of mortality on the hulks ranged upwards from five per cent, again depending on who was counting. It was a practice of the British to sometimes offer the deceased the trappings of decent burial. They were placed in a proper coffin and carried to the sands and soils of a shore. The coffin, however, had a false bottom and would be reused often.

In 1908, the Prison Ships Martyr’s Monument was constructed in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, New York. Inspired by the offense of the prison ship Jersey, which had moored nearby, and drawing from the consensus of history, it asserted that 11,500 Americans had died in the hulks in the U.S. and abroad during the Revolutionary War alone.

In 1908, the Prison Ships Martyr’s Monument was constructed in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, New York. Inspired by the offense of the prison ship Jersey, which had moored nearby, and drawing from the consensus of history, it asserted that 11,500 Americans had died in the hulks in the U.S. and abroad during the Revolutionary War alone.

Adapted from The Foreign Burial of American War Dead by Chris Dickon. Dickon is an Emmy-winning former public broadcasting producer, reporter and writer. He has published several books on lesser-known aspects of American history. He lives in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Great article but you desperately need an editor. Misselling and typos abound.