“The slaughter on the Western Front was the culmination of a ‘tactical evolution’ that could be traced back as far as the American Civil War. Yet few, if any, took the time to digest those lessons.”

By Jim Stempel

ON JULY 1, 1916, the British Army mounted one of the most ambitious offensives ever undertaken. It quickly turned into one of the greatest bloodbaths in military history.

At exactly 7:30 a.m., some 100,000 men went “over the top” in a coordinated advance across a 15-mile front against German lines near the Somme River in France.

Orchestrated to relieve pressure on French forces tied down by heavy fighting at Verdun, the British attack was to drive a wedge through the enemy line, thus sending the German army tumbling back toward Berlin.

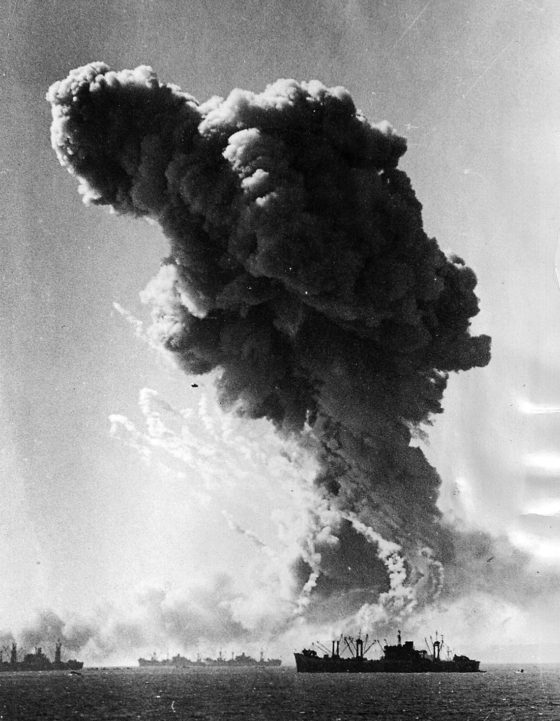

H-hour was preceded by a colossal artillery bombardment that rained shells over German lines non-stop for more than a week. Unleashed to soften up enemy defences, the cannonade saw more than a million shells fired from almost 25,000 heavy guns. Remarkably, the shelling had almost no effect. The Germans were dug in far deeper than the British anticipated and the artillery failed to destroy the miles of barbed wire that protected the entrenched defenders. The explosion of 17 massive underground mines and a “creeping barrage” laid down in front of the advancing British troops were both supposed to ensure success that fateful morning. Neither tactic proved effective.

Tragically, the British troops found themselves advancing across a “no-man’s-land” where virtually every inch of the terrain was raked by artillery, rifle and machine gun fire. The result was mass slaughter. By day’s end the British had suffered some 57,470 casualties, 19,240 of whom lay dead.

“I heard the ‘patter, patter’ of machine guns,” A sergeant in the Tyneside Irish Brigade recalled the utter futility of the advance. “By the time I’d gone another 10 yards there seemed to be only a few men left around me; by the time I had gone 20 yards, I seemed to be on my own. Then I was hit myself.”

Despite this dreadful beginning, the Somme Offensive would continue for another five fruitless months, with neither side gaining significant advantage. As historian Robert L. O’Connell notes, “In the end each would endure over 600,000 casualties for a prize of six or seven miles of strategically worthless ground along a 30-mile front.”

By the time of the Somme, warfare had morphed into a modern, industrial meat grinder — one that was chewing up men as fast as they could be fed into the conflagration, yet with no realistic hope of success. To those in the thick of the fighting, the Apocalypse seemed surely to have arrived. How had this come to pass?

The truth is, the seeds of the Somme had been gradually sown gradually over decades. The slaughter on the Western Front was the culmination of a ‘tactical evolution’ that could be traced back as far as the American Civil War. Yet few, if any, took the time to digest those lessons.

The war between the Union and the Confederacy began with armies fighting Napoleonic-style battles with large concentrations of men marching in formation across open fields to deliver volleys at very close range. These early encounters, like Bull Run or Shiloh, were set-piece affairs reminiscent of earlier 19th Century engagements such as Waterloo and Austerlitz. But as the fighting continued, the battlefields would increasingly bear a chilly resemblance to the killing grounds of the First World War’s Western Front. Cold Harbor and later Petersburg looked more like Verdun and, yes, even the Somme than anything out of Bonaparte’s era. How did tactics change so drastically so quickly? Look no further than the weaponry.

Rifled Muskets

For the 150 years leading up to the Civil War, the standard issue infantry long arm had been the smoothbore flintlock musket, a crude weapon with an effective range of 100 yards at best. Due to its slow rate of fire, inaccuracy and limited range, armies armed with muskets were forced to fight in large, tightly packed formations.

In order to have any effect, armies would march with parade-square discipline en masse to within a few paces of the enemy and then discharge their weapons in coordinated volleys. But in the early 19th Century, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing. Advanced manufacturing techniques allowed factories to mass produce new, and surprisingly accurate firearms quickly and cheaply.

By 1861, the standard issue infantry weapon in the United States had changed from the old smoothbore flintlocks of the Revolutionary War to the 1861 Springfield rifle, a percussion-cap firearm that could hurl a .58 caliber bullet 700 yards with lethal accuracy. It represented an enormous leap in the technology of meting out death. Suddenly, whole regiments could spew torrents of lead at one another with pin-point precision. Armies that once fought in open fields were forced to seek cover behind earthworks, trenches and sandbags.

Artillery

Likewise, at the beginning of the Civil War use of artillery in the field was rooted in the 18th Century. Batteries were generally assigned to individual infantry units, and went into action as an adjunct to that unit alone. That limited use of artillery would change radically during the course of the war. By conflict’s end, the deployment of artillery would become far better organized, allowing multiple batteries to engage a single target on a coordinated basis across a wide front. And like the infantryman’s rifle, improvements in artillery technology had by 1861 leap-frogged the old smoothbore cannon with rifled pieces, weapons that were now vastly improved in terms of range, accuracy, and lethality.

Over time the effect of rifle fire and the coordination of artillery would increase the lethality of the Civil War battlefield to the point that the old Napoleonic tactics were rendered obsolete. Sadly, no one – save the troops themselves – seemed to take notice, thus over a four-year period Civil War battles became little more than venues for mass murder. By war’s end, and simply to avoid the increasingly lethal nature of the modern battlefield, the troops began to entrench, thus adding the final tactical flourish to the hundred year evolution.

Harbingers of 1916

On June 3, 1864 that tactical evolution emerged in its grim, complete form at Cold Harbor, Virginia, when Ulysses S. Grant sent almost 50,000 troops into the teeth of a skillfully prepared Confederate defense across a six-mile front, an event covered in dramatic detail in my newest novel titled Windmill Point.

Blown to pieces in a fusillade of artillery and small arms fire, some 7,000 Federal troops would go down in little more than 15 minutes. By all accounts, it was a horrific spectacle that was frighteningly similar to that day 52 years later along the Somme.

Since war first emerged as a human enterprise around 10,000 BC, victory had generally turned on the ability of men, massed for combat, to storm strong points and prevail in battle. No longer would that be the case. The evolving technology of war had simply rendered obsolete the ancient tactic of the massed infantry assault. Weaponry, not men, would from that point forward rule the field of battle. Yet this truth, so obvious to us now as we gaze back across the bloody landscape of the American Civil War, had yet to make an impression on the battle captains of World War I. Hence virtually an entire generation of European males would be swept away in the apocalypse that was the dawn of 20th century warfare.

Cold Harbor may have been a window into the apocalyptic nature of the warfare that was soon to come, but that window shed light on a far deeper issue as well. Because in many ways, and across many applications, the question of whether we Homo sapiens will ultimately be the masters of our evolving science and consequent technologies, or mastered by them, remains with us still.

Jim Stempel is the author of seven books, including nonfiction, historical fiction, spirituality, and satire. His articles have appeared in numerous journals including North & South, HistoryNet, Concepts In Human Development, New Times, and Real Clear History. His novel, Windmill Point, has been selected as a finalist in the Chanticleer Literary Competition for best Civil War historical fiction. He is a graduate of the Citadel, Charleston, South Carolina, and lives with his wife and family Maryland. Feel free to explore his website at: www.jimstempel.com

Jim Stempel is the author of seven books, including nonfiction, historical fiction, spirituality, and satire. His articles have appeared in numerous journals including North & South, HistoryNet, Concepts In Human Development, New Times, and Real Clear History. His novel, Windmill Point, has been selected as a finalist in the Chanticleer Literary Competition for best Civil War historical fiction. He is a graduate of the Citadel, Charleston, South Carolina, and lives with his wife and family Maryland. Feel free to explore his website at: www.jimstempel.com

Penmore Press is running a 48 hour promotion on “Windmill Point” — a kindle edition for $2.99 — sale ends 1/27/2017. Thanks!