“Another Axis power also hoping to stave off defeat considered its own version of the kamikaze.”

IN 1944, JAPAN’S MILITARY SHOCKED THE WORLD when it sent the kamikaze into battle.

With the emperor’s fleet dwindling in the face of the numerically superior U.S. Navy, the leadership in Tokyo called on volunteer pilots to crash explosive-laden aircraft into enemy ships. Not only would these flying bombs do far more damage to Allied vessels than most naval guns or torpedoes – the sacrifice of the pilots was calculated to demonstrate the unflagging resolve of the Japanese people.

The kamikaze made their combat debut at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The first ship to fall victim was the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia. In the days that followed, dozens of suicide pilots would strike the Allied task force.

By war’s end, nearly 4,000 Japanese volunteers would fly kamikaze missions – most of them teenaged trainees. More than 85 percent of the fliers would miss their targets or be shot down by anti-aircraft gunners. The rest succeeded in destroying more than 300 ships, some as large as escort carriers. While the kamikaze certainly horrified Allied ships’ crews, ultimately they had little impact on the course of the war.

Surprisingly enough, half a world away another Axis power also hoping to stave off defeat considered its own version of the kamikaze. They were known as the Leonidas Squadron.

Germany’s Suicide Squad

Named for the legendary ancient Spartan king who died in action with his 300-man army at Thermopylae, the Leonidas Squadron or Staffel 5 was organized in 1944 as part of the elite bomber/recon wing Kampfgeschwader 200.

The group was comprised of 70 volunteers, all of whom were required to sign a contract in which the recruits essentially forfeited their lives. The document specifically referred to “suicide missions” and “human glider bombs.”

“I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death,” the agreement read. [1]

Pilots in the Leonidas Squadron were trained to fly the experimental Fi-103R Reichenberg, a manned version of the V-1 flying bomb. The volunteers would steer the 26-foot long aircraft, which could fly 350 km (200 miles) at speeds approaching 800 km/h (55 mph), into enemy targets like ships or bridges. The Nazis hoped that the pilots would be able to bail out before impact, but if it proved necessary crews were expected to die with their aircraft. In any event, the proximity of the cockpit to the Fi-103R’s jet engine made the chances of survival hitting the silk less than 1 percent. [2]

The idea of the suicide squadron was first proposed by senior SS official Otto Skorzeny and Hajo Herrmann, a veteran Luftwaffe bomber pilot and tactician. Like the kamikaze, it was conceived as a means of redressing the gaping military imbalance between Nazi Germany and the Allies as well as a way of demonstrating the regime’s commitment to the cause. Surprisingly, Hitler was wary of the concept at first but as the war continued he finally embraced it, so long as he alone decided when suicide bombers would be ordered into battle. [3]

While consideration was given to unleashing manned missiles on the Normandy invasion fleet and Soviet power stations, problems with the Fi-103Rs kept Staffel 5 grounded. It wasn’t until the final days of the war that 35 of the volunteers flew a random assortment of Luftwaffe aircraft into Soviet-controlled bridges over the Oder River near Berlin. The Nazis claimed to have destroyed 17 bridges with their so-called “self-sacrifice” sorties between April 17 and 20; historians have found evidence of only one successful strike. The unit was grounded permanently when the Red Army captured its airfield.

Sonderkommando Elbe

Two weeks prior to Staffel 5’s fatal debut, another Luftwaffe group named Sonderkommando Elbe initiated its own de facto suicide campaign.

While not explicitly ordered to their deaths, pilots of this all-volunteer unit had the unenviable task of using their Bf-109G Messerschmitt fighters to collide with and destroy Allied bombers. Although the pilots were encouraged to bail out if possible, ramming a bomber in mid-air would more than likely prove to be a fatal maneuver. Nevertheless, the recruits were instructed to slam their fighters into the cockpits of targeted bombers to kill the enemy aircrew or at the very least to drive into the wings.

The campaign, which kicked off in early April of 1945, was intended to force Allied commanders to recall their planes long enough for German factories to crank out sufficient numbers of new fighters like the Me-262 jet fighter.

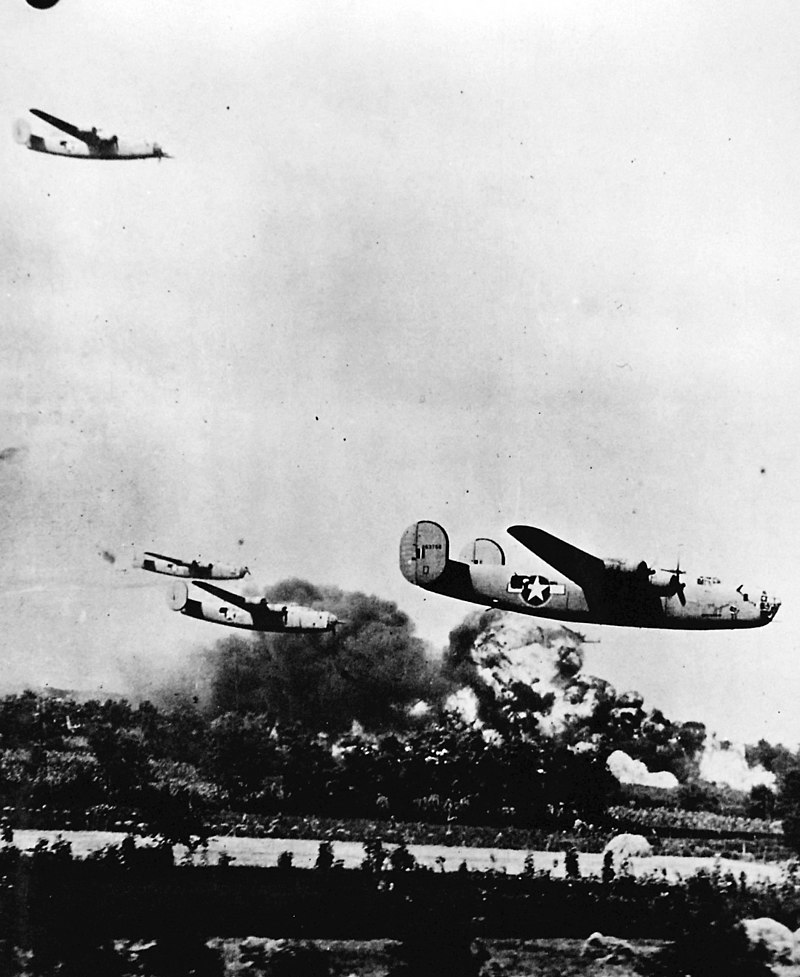

Only one mission was flown. On April 7, 1945 more than 180 Sonderkommando Elbe aircraft attacked a large formation of American B-17s and B-24s escorted by P-51 Mustangs. The American escorts immediately fell on the attacking fighters driving most of them away. Ultimately, fewer than two-dozen Allied bombers were rammed; eight of these were destroyed. Out of the German pilots who managed to make it through to the bombers, only four survived. [4]

Allied Suicide Pilots

While suicide missions were never officially part of Allied strategy, there were a number of instances of British, Polish, American and Soviet pilots sacrificing themselves to destroy enemy targets. Here are some examples:

One of the first casualties of the war was Leopold Pamula, a Polish pilot who intentionally slammed his outclassed PZL P.11c into a German aircraft in the opening hours of the war.

On the first day of the Nazi invasion of Russia, nine different Soviet pilots rammed enemy bombers with their obsolete aircraft. One such pilot, Lt. I. I. Ivanov, was made a Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously for driving his plane into a German He-111 bomber. A month later, a female pilot named Yekaterina Zelenko brought down a Messerschmitt fighter with her plane, the only woman to have performed a ramming mission in the war. In total, 270 Soviet pilots intentionally struck enemy planes between 1941 and 1945.

During the Battle of Britain, a number of RAF pilots were celebrated for using their own aircraft as weapons when the need arose. On Aug. 18, 1940, a reservist destroyed a He-111 with his Avro Anson killing himself in the process. Not all were so unlucky. A pilot from No. 85 Squadron used the wingtip of his Hawker Hurricane to poke holes in a Heinkel bomber when his plane’s guns ran out of ammunition. Although the British fighter was crippled, the flier survived. The bomber crew wasn’t as lucky – all perished. In September, Sgt. Ray Holmes used his Hurricane to slice the tail section off a Dornier Do-17 bomber over London. Both planes were destroyed; Holmes parachuted to safety.

While Americans were appalled by Japanese suicide bombers in 1944 and 1945, ironically the United States’ first hero of World War Two, Colin P. Kelly, was heralded for flying his own plane into an enemy warship in much the same way kamikazes would do two and a half years later. According to the story, only three days after the Pearl Harbor raid, Kelly’s B-17 Flying Fortress came under attack by Zeroes after bombing a Japanese warship off the Philippines. The doomed pilot kept his stricken plane in the air long enough for the crew to escape, at which point he deliberately plowed his Flying Fortress right into the smokestack of the Japanese ship Ashigara.

War Department propagandists made full use of the story and soon liberty ships, schools, streets and highways were being named in Kelly’s honour. His likeness graced a line of patriotic posters and even the song “There’s a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” referenced his heroism. It was later reported that the pilot actually bailed out with his crew, but died when his parachute failed to open. The suicide mission was later revealed to be a complete fabrication. [5] And once Japanese pilots began their own suicide missions, the Kelly myth was conveniently forgotten.

(Originally published Feb 27, 2013)

As a slightyly happier aneccdote… the airfield Sonderkommando Elbe operated off was temporarily put back in use in 2003 when it bacame the largest base for German Army and Fedaral Police helicopter flying relief missions during the Elbe floodings that year. Their main area of operations was the area around Stendal, where the Americans and Soviets liked up.

Thanks for the update on that. You are right, it is a happier anecdote! Thanks, as always for your contributions, Burkhard!

The tidbit about Colin Kelly was like dessert in this blog… Nice writing and summaries.

Weren’t there also suicide torpedoes that the Japanese used?

Shinyo-class speed boats were essentially suicide torpedoes, yes!

Should also mention the B-26 during the Battle of Midway that attempted to ram into the command bridge of Nagumo’s flagship, the Akagi. Nagumo was apparently pretty flustered by the incident because Americans weren’t supposed to do that sort of thing.