ON JULY 4, 1776, 13 of GREAT BRITAIN’S North American colonies declared their independence. And while New York, Massachusetts, Virginia and a host of others joined in that rebellion, one future U.S. state was notably absent from the patriot roll call – Vermont.

Situated east of New York and west of New Hampshire, Vermont was no friend of its neighbouring colonies. In fact, the territory had spent the years leading up to the revolution locked in a dispute with the colonies on its border over land. Both New York and New Hampshire had laid claim to Vermont — many Americans at the time considered the inhabitants of the territory as little more than troublemakers.

Hostilities between Vermont residents and encroaching New Yorkers even led to bloodshed in March of 1775 when colonial administrators and militia clashed with settlers leading to the deaths of two locals. The incident became known as the Westminster Massacre. After the violence, Vermont raised its own army to safeguard its borders. They became known as the Green Mountain Boys. The name was a play on the French words vert meaning “green” and mont meaning “mountain.”

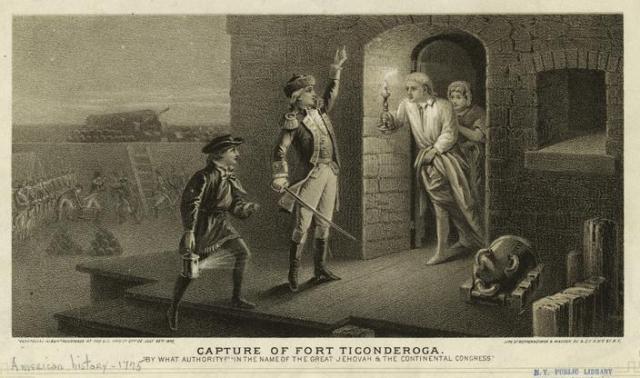

Despite stormy relations with its neighbours, Vermont still leant its support to the 13 colonies as tensions between the Continentals and Great Britain heated up in 1775. In fact, less than a month after the battle of Lexington and Concord (the first clash of the War of Independence), a regiment of Green Mountain Boys, under the command of Ethan Allen, swooped in and captured the British fort at Ticonderoga, New York. The stone fortress sat on the western shore of Lake Champlain, just opposite from Vermont territory. Allen’s men, along with a detachment of Connecticut militia under the command of Benedict Arnold, also grabbed other British held forts in the area, like Crown Point and Fort George, and even captured a Tory settlement in Quebec. Two years later, the Green Mountain Boys would take part in the Saratoga campaign – a decisive victory for the American cause that saw a British army from Quebec under John Burgoyne shattered as it marched down the Hudson River valley.

Yet despite its formal participation in the revolution, the Continental Congress refused to recognize Vermont’s legitimacy, largely at the insistence of New York, which still considered it something of a rogue state.

So in January of 1777, the territory declared a separate independence establishing itself as a sovereign nation — the Republic of Vermont. It issued its own currency, set up a national postal service and even named its own president: Governor Thomas Chittenden. Delegates from the tiny republic’s various towns and counties gathered at a tavern in the village of Windsor to draft Vermont’s own constitution – one that extended the vote to non-property owners and even outlawed slavery. It was the first document of its kind in the New World and was implemented a full decade before the U.S. Constitution was written.

Interestingly, Vermont’s go-it-alone approach to nation building was short lived. When redcoats and their Mohawk allies invaded the region in 1780 to burn settlements and take prisoners, the Green Mountain Boys’ own Ethan Allen, his brother Ira and Gov. Chittenden sent out feelers to British authorities in Quebec fo secret negotiations. While the talks were ostensibly an attempt to secure the release of captured militiamen, the ultimate objective was hammering out a separate peace – one that might even lead to a resumption of crown control over the former colony if necessary. Although few details of the discussions were formally made public, when news of them leaked to Vermont’s assembly (and later in other states’ legislatures) it created an epic scandal. The debacle became known as the Haldimand Affair – named for the British governor at Quebec, Frederick Haldimand.

Despite claims by Allen and Chittenden that the prospect of a reunion with the crown was little more than a ruse intended to secure the release of prisoners, it was nonetheless politically damaging for the Vermont’s government. The Continental Congress even pondered an all out invasion of the territory to bring the rogue republic to heel.

The negotiations stalled and soon British troops were clashing with Vermont militia on the state’s western border.

Following the English defeat at Yorktown in 1781, Vermonters who still believed security lay in peace with the crown suddenly changed their tune. With the Revolutionary War drawing to a close, Vermont sought to resolve its land claims with its neighbours. Eventually, the republic agreed to pay New York $30,000 in silver for land and by 1790, Vermont ceased to be an independent republic and formally joined the United States.

The Green Mountain Boys would be disbanded following the revolution, but its regiments would be reconstituted during the War of 1812, the Civil War and the Spanish American War. Today, the state’s national guard still bears the name.

Again, a fascinating well told story!

Excellent stuff from one of my favorite blogs.

Very, very interesting tidbits that will never make textbooks! Great knowledge and research, sir!

Thanks, Mustang! You should see the next story I’m working on. I was amazed! Stay tuned.

I am!