“Although civil wars can be among the bloodiest and most acrimonious of all armed conflicts, this particular contest was utterly genteel by comparison.”

THE TERM “civil war” is something of an oxymoron. Just like “jumbo shrimp” or “original copy,” the two words are inherently contradictory. After all, there is little room for civility amid the violence and savagery of armed conflict. Yet, leave it to the Swiss (those masters of neutrality) to give us at least one example of a truly civil war — the Sonderbundkrieg of 1847.

The conflict was a month-long fight between Switzerland’s reform-minded, predominantly Protestant federal government and a rebel army of conservative Roman Catholics. And although civil wars can be among the bloodiest and most acrimonious of all armed conflicts, this particular contest was utterly genteel by comparison.

Need proof? Consider the fact that the nationalist army commander actually refused the government’s offer to equip his troops with Congreve rockets because he feared the weapons might cause too much distress to the enemy. That same general also passed his battle plans along to the rebel leaders — not because he was a traitor, but rather that he wanted to convince his opponents to surrender and avoid needless bloodshed. And the humanity wasn’t confined to one side — citizens of rebel towns greeted federal invaders with open arms. Then there were the war’s battles, largely bloodless affairs. The fighting itself only lasted for three weeks. And out of 150,000 combatants, fewer than 100 died in action. As for the wounded, there were standing orders to national troops to provide medical care to the injured enemy. Now you can see why the Sonderbund War just might be the most polite conflict in history.

Prelude to War

The fighting had its roots in the early 1840s with the rise to power of a reform-minded liberal party in the Swiss national legislature or Tagsatzung. The new regime embarked on an ambitious plan to minimize the power of the Catholic church. And that wasn’t all. The reformers also sought to draft a new Swiss constitution, one that would unify a number of the country’s districts, known as cantons, into a more cohesive national confederation. The move was strongly opposed by a group of seven predominantly Catholic cantons spread across central and western Switzerland. Ironically, the aggrieved regions of Lucerne, Fribourg, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug responded to the pressure to unify by forming their own union called the Sonderbund to oppose the federal government’s plan.

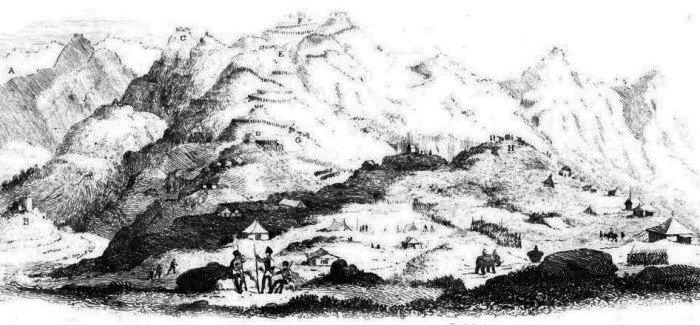

Throughout the fall of 1847, the government in Bern set out to break up the confederacy of rebel cantons – it organized a national army of 100,000 troops, furnished by loyal regions of Switzerland, and placed the Napoleonic war hero Guillaume-Henri Dufour at is head.

While most loyal cantons joined the coalition, in true Swiss fashion, two remained neutral, opting to stay out of the coming fight — Neuchâtel and Appenzell Innerrhoden.

Although, the 61-year-old Dufour reluctantly accepted his appointment to lead the federal forces, he vowed to keep the level of violence in the coming hostilities to a minimum.

Opening Blows

For the first five days of the war, it was the Sonderbund that was on the offensive, snatching up towns and securing strategic mountain passes leading into rebel territories. Then on Nov. 9, the federal troops made their move – an incursion into the canton of Fribourg.

Dufour brought his troops to the very gates of the city of Fribourg on Nov. 11. Armed with 60 artillery pieces to breech the walls, the force surrounded the town and waited. On Nov. 13, the general sent a message to the defenders in which he (amazingly) itemized details of his plans for the coming assault. The surprising disclosure was intended to warn the rebels to give up the city in order to save lives. The opposition asked for a daylong ceasefire to ponder the proposal — Dufour granted them the time.

The quiet was shattered when a contingent of federal troops misread their orders to hold in place and instead probed the rebel defences along the city’s walls. A brief skirmish ensured. Eight attackers were killed and assault was repulsed. Despite the victory for the rebels, Fribourg’s commander still put Dufour’s offer for quarter to a vote. The defenders eagerly accepted the terms and the city was handed over to the national army without further incident. The rebels lay down their arms and were paroled to their homes. Meanwhile, a force from the Catholic canton of Uri that had already organized to march to the relief Fribourg learned of the surrender on Nov. 17. They turned south to invade federal territory at Ticino instead.

The Battle of Gisikon

Back in Fribourg, Dufour regrouped for an incursion into another rebel canton: Lucerne.

As he prepared his troops for a second (hopefully bloodless) campaign, the neighbouring region of Zug pulled out of the rebellion on Nov. 21. Federal troops soon marched into the territory and were greeted by their former enemies with open arms. Buoyed by this latest surrender, Dufour pushed his army on into Lucerne.

On Nov. 23, the force collided with the rebel army at Gisikon near the city of Lucerne. As federal troops tried to cross the Reuss River, a concealed battery of rebel guns opened up. Dufour’s men traversed the river under fire and assaulted the rebel line. It would take three separate charges before the Catholics were pushed from the high ground. Thirty-seven national troops died in the two-hour clash. It would be the last time in history that the Swiss troops experienced combat. With the rebel army defeated, the canton of Lucerne capitulated.

Over the next week, the remaining holdout rebel enclaves would also throw in the towel. The Sonderbund was broken.

Aftermath

With the rebellion over, the leadership of the uprising offered their resignations from public office and were replaced with leaders more friendly to the national government.

All told, the federal army lost fewer than 70 men in the entire war; the rebels suffered less than 30 dead.

The new Swiss constitution eventually was ratified and the federal government fined the two neutral cantons of Neuchâtel and Appenzell Innerrhoden for not supplying troops to suppress the uprising. The funds would go to compensating widows and orphans of the war. A consummate humanitarian, Dufour would eventually go on to organize the International Red Cross.

(Originally published on MilitaryHistoryNow.com on Jan. 18, 2013)

My grandfather’s Swiss grandparents emigrated from Switzerland in 1851. I know very little about why they left or the political climate at that time. They were residents of Bern. A family legend claims they left because of forced conscription into the army. Thank you for the insight.

I have a similar conundrum in my direct maternal line. My 4th great grandmother emigrated from Switzerland to the US ~1948 at the age of 18. Other ancestors always had an obvious reason for leaving the lands of their birth…the bloodshed in the Alsace region, the potato famine in Bavaria, etc. But this is one I can’t seem to find a motivation for. The Swiss civil war had been incredibly short and un-bloody, and was well over by 1948. So far no luck finding anything related to her immigration apart from a census record stating that she came to the US in 1948, so I’m at a dead-end for now. All I know apart from that, is that the records state that she and her parents were born in Switzerland. My husband has suggested that maybe her family had been part of the losing side, but that seems a little melodramatic considering how polite the whole affair was.

A lot of Swiss emigrated because they were poor and wanted a better life – Switzerland wasn’t rich in the 19th century. And some communities encouraged emigration to get rid of some of the poor. That changed in the 20th century, but the difference between the US and Switzerland would still be quite significant in 1948, especially for the poor. Sometimes, troublemakers were encouraged to emigrate as well – my grandfather had to travel to the USA in the 1930s to fetch his brother, who was a bit of a red firebrand. Since they were travelling through Nazi Germany and with a Nazi ship (because it was the cheapest, I was told) that caused some trouble on the way back, but they safely arrived back in Switzerland.

Wish all wars were the same. All nations need to learn this history

A town named “Giskilon” does not exists. It should be “Battle of Gisikon”. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderbund_War#Battle_of_Gisikon

Notice no diversity in Switzerland. That’s why the war was so civil, they’re our own kind.

No diversity in Switzerland? The country with four different languages? Tell me you’ve never been to Switzerland without telling me you’ve never been to Switzerland.

Small typo: It’s Gisikon, not Giskilon (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gisikon)

Thanks for the correction. We fixed it.

Hi ! You have to fix “Giskilon” to Gisikon ! Best regards from Switzerland !

Giskilon sounds like something out of Lotr. You probably mean https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gisikon

cheers